Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Where *isn't* Planet 9?

Astronomers are still looking for a possible giant planet far beyond Neptune.

For a few years now, some astronomers have been looking for another planet in the solar system, one much larger than Earth that orbits the Sun far beyond Neptune. Not-so-tongue-in-cheekily, they've been calling it Planet 9.

That space past Neptune isn't empty; there are millions of small(ish) objects out there made of ice and rock, collectively called Trans-Neptunian Objects (or TNOs). Technically, this includes Pluto, which may be the largest TNO (it's the biggest we've seen so far), but there are many others. They're so far from Earth, at least 4.5 billion kilometers, that they're hard to detect even in big telescopes. Besides Pluto (and its moon Charon), the first one wasn't discovered until 1992.

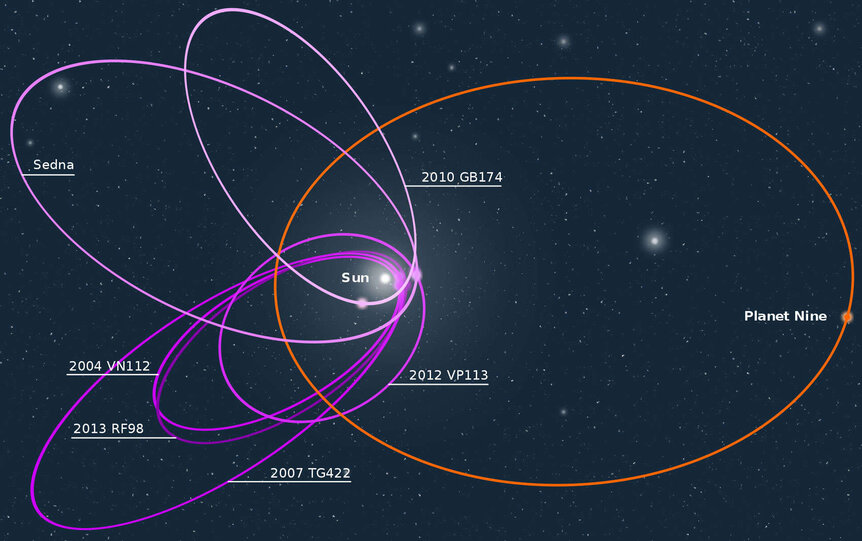

Thousands are now known, and some are very far from the Sun indeed. Not too many of these extremely distant ones are known, but as more have been discovered something weird turned up: Their orbits were roughly aligned. You'd expect their orbits to be somewhat randomly aligned, ellipses tilted and rotated every which-way. Instead, they all seem to have their long axes pointed in about the same direction.

That's very unlikely to happen by chance, which is why the idea of Planet 9 came up. A massive planet orbiting that far out can, over time, gravitationally affect those TNOs and align their orbits.

Not long ago astronomers Mike Brown and Konstantin Batygin (the two original people proposing the existence of the planet) used the alignments of the TNO orbits to back-calculate the potential location of the unseen planet in space. It's a kind of treasure map to find the planet.

In a new paper they've put that map to use, looking through survey data in a hunt for Planet 9.

The Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) is a 1.2-meter telescope in California equipped with a massive camera that can cover 47 square degrees of sky in one go — the full Moon's area on the sky is about a quarter of a degree, for comparison — covers the entire northern sky and some of the southern sky every three nights. It's looking for objects that either move or change brightness. That includes asteroids, comets, TNOs, supernovae, gamma-ray bursts… and maybe Planet 9.

Brown and Batygin wrote software that simulates where Planet 9 would be and how bright it would appears for various values of its size, reflectivity, and orbital shape. They created a database of positions and brightnesses for it, and then combed through the ZTF database to look for it, going through the past three or so years of observations since the facility started its survey campaign.

Spoiler alert: They haven't found it. At least not yet.

But they were able to put some interesting limits on the planet given their non-detection. For example, some of their models show that it's possible Planet 9 might be smaller in size and closer to the Sun than their original estimates. This makes it brighter and easier to spot, which is what motivated them to look at ZTF in the first place.

While they can't rule this out, it now seems less likely because they didn't see it in the survey. They ran 100,000 simulations of various parameters for the planet, and looked to see if the ZTF would've seen it if it were indeed smaller and closer to us. They determined that it would've been seen in the survey about 56,000 times out of the 100,000, so just looking at that their non-detection indicates the chance it's smaller and closer is now less than 50%, making it more likely it's farther out, bigger, and fainter.

That's a little disappointing, but not enough to rule anything out — there's still a chance ZTF can find it (as long as the planet isn't in the southernmost part of its orbit, where ZTF cannot see due to its latitude on Earth). And if it's fainter it may be beyond the limits of ZTF, and we'll have to wait for bigger telescopes coming online soon (like the Vera Rubin Observatory).

I'll note that the astronomical community isn't entirely convinced that Planet 9 exists. Papers come out every now and again trying to explain the TNO orbital alignment as what's called a selection bias; it's not real but due to the way we find these objects: Where in the sky we look, when, and so on. Brown and Batygin have also published rebuttals to these, saying when you account for biases the orbits are still non-randomly aligned.

I actually quite like all this. I would love for there to be another major planet in the solar system. Besides the romance of it — anther planet! — it would also give us huge insight into planetary formation and evolution. The science we'd get from it would be amazing.

But I'm also enjoying the back and forth between astronomers. This is how science works, and it works well. Brown and Batygin have made an extraordinary claim, and it's up to them and other astronomers to try to figure out ways they can be wrong.

The proof in this case will be in the planeting. If they find it, hurray! And if, at some point, surveys cover the whole sky to some reasonably faint limit and it's still not found, well then we'll have learned something from that as well. It's not as much fun, but it's still an important result.

We may not have too much longer to wait to find out.

P.S. Full disclosure: Mike Brown is a colleague and friend of mine. I've been interested in the idea of another planet in our solar system since long before I knew him, though, so I'd certainly be writing on this topic either way, and try to be fair in my analysis.