Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

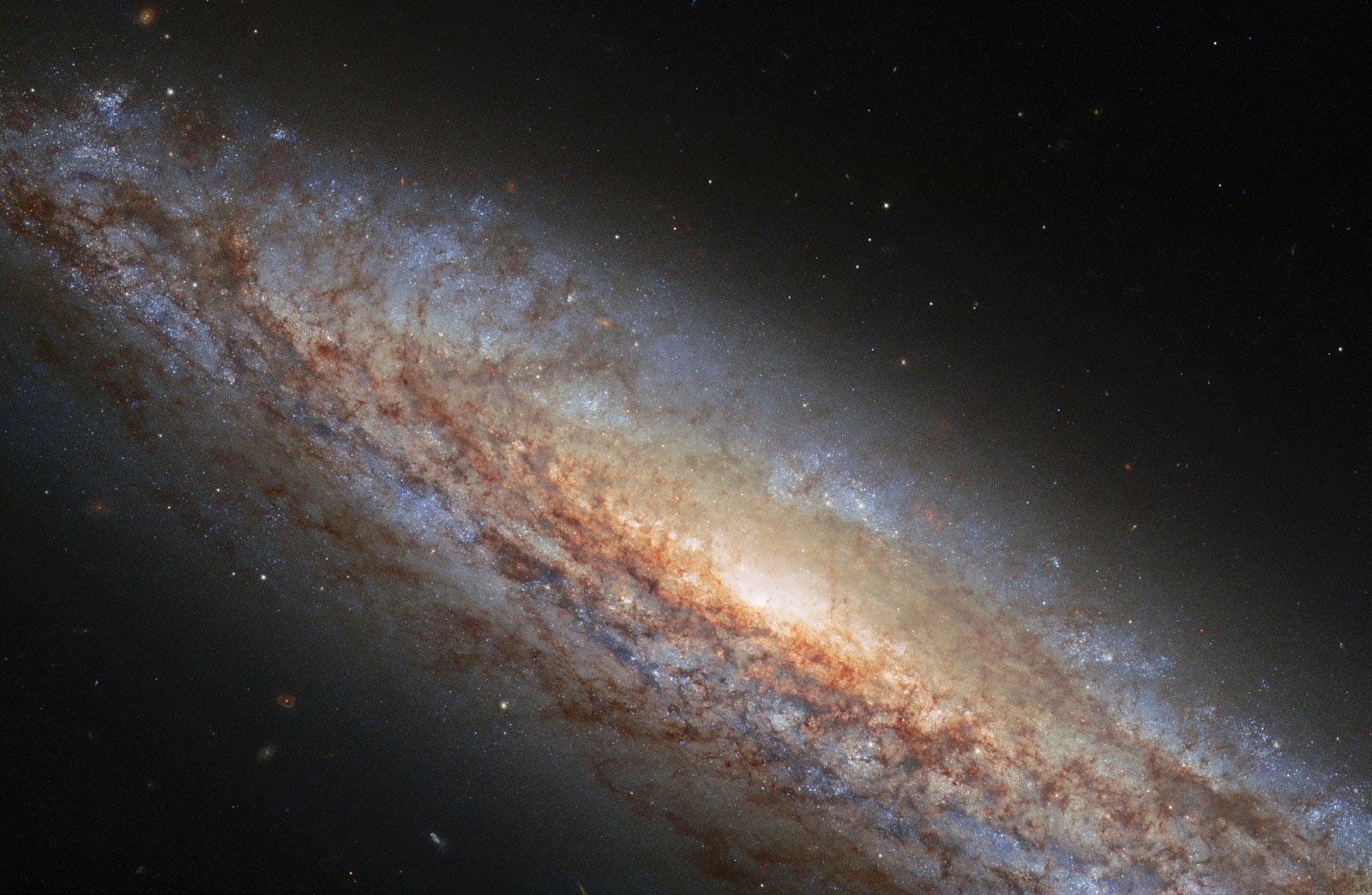

Hubble portrait of a galaxy shows it shines in stellar birth and death

NGC 4666 is gorgeous, and shows us the circle of stellar life.

Three things I love to write about are gorgeous spiral galaxies, exploding stars, and astronomical mysteries.

This makes NGC 4666 a perfect target: It's certainly spectacular, a star blew up in it, and it's not clear why the detonated star's corpse behaved the way it.

NGC 4666 is a spiral galaxy similar to the Milky Way, and we see it just a few degrees off of it being edge-on, so it looks like a highly elongated ellipse. That's an illusion borne of perspective; seen face-on it would likely look nearly circular.

Right away I found an issue with it: Despite being relatively close to us, the distance isn't well known. Judging from the brightness of an exploding star in it (more on that in a sec), one source says it's about 48 million light years away. However, a different paper looked at a lot of different methods and found a distance of 55 million. We also know that due to the expansion of the Universe, distant galaxies move away from us, and the farther they are the faster they recede. This is called redshift, and given NGC 4666's redshift I get a distance to it of 72 million light years!

However, the galaxy is located in the same part of the sky as the massive Virgo Cluster of galaxies, and if it's falling into it due to the cluster's combined gravity that could skew the redshift (one paper accounting for that gives a distance of closer to 85 million light years!). A likely guess is it's about 65 million light years away then, just by roughly averaging the different values.

NGC 4666 is what's called a starburst galaxy. It's undergoing a mildly intense episode of star birth, cranking them out at a rate 3-7 times as much as the Milky Way. This was detected in radio waves and X-rays; the powerful winds blown out by young massive stars interact with gas around them and glows in light we cannot see. However, there are some optical (visible light) filaments that can be seen in the light emitted by warm hydrogen, and I swear in the Hubble image above the darker dusty tendrils look like they're sticking up, perpendicular and away from the galaxy's disk. That might be an illusion, but I'll note they looked that way to me before I knew the galaxy was blowing this newborn-star superwind.

Interestingly, though, that's not why this galaxy was observed by Hubble. Instead, it's because it was host to an exploding star, a supernova. Usually when you think of those you might picture a massive star like Betelgeuse at the end of its life. That's called a core collapse or Type II supernova.

But this was a Type I, when a white dwarf explodes. These are the leftover cores of less massive stars like the Sun after they run out of nuclear fuel. The star swells into a red giant, blows off its outer layers, and exposes its hot, dense core to space: a white dwarf. If the star was in a binary system the intense gravity of the white dwarf might steal material from the other star, which piles up on the surface. Under the right conditions it can get squeezed so hard by the powerful gravity that the pilfered hydrogen undergoes thermonuclear fusion, disrupting the entire star. It's also possible it orbits a second white dwarf, and they eventually spiral together and collide. Either way: KABOOM! Supernova.

There's a prediction that about 500 days after the supernova event, the expanding debris undergoes a complicated atomic process that causes the amount of visible light it emits to drop suddenly, and it gets much brighter in infrared. This is hard to observe because typically these supernovae and far away, and by the time years have passed get pretty dim.

Happily, though — well, not for the star or anyone nearby, but for us — in December 2014 a Type Ia was discovered in NGC 4666. Called ASASSN-14lp (because it was first seen by the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae), it was luminous for its type but otherwise pretty normal. But that's good: Being close by in a galactic sense and bright made it easier to see it at late times. So around 860 and 950 days after the event, Hubble observed the galaxy and the supernova to see what's what.

It turns out ASASSN-14lp didn't want to play by the rules. Not only did the optical light not drop precipitously, the observations showed it was lingering, with the amount of light it was giving off dropping very slowly with time. A handful of other supernovae have been seen to do this, and it's not clear why. The explosion creates all sorts of elements, including radioactive ones that decay and dump energy into the surrounding material; a slowly decaying one might give the expanding debris enough energy to stay brighter longer. It's possible the debris itself changes, becoming able to absorb energy from decay better, so again it stays brighter longer.

Unfortunately, the observations here can't tell which is happening (or if something else is going on). However, any single supernova is unlikely to crack this case; we need to observe a lot of them and look at the aggregate data to figure out what's happening.

I'll note that even after three years, ASASSN-14lp was still blasting away light at a rate that made it 100,000 times brighter than the Sun. Supernovae are fierce.

These Type Ia supernovae are also used to better understand why the Universal expansion is accelerating. They're pretty useful astronomically.

I'll also note that supernovae like this make lots of elements like iron and calcium that are sent out into space and can hit gas clouds. These clouds collapse to form stars and planets; this happened some 4.6 billion years ago right here, and those elements eventually became you. Yes, you.

We owe our existence to supernovae, and it may be possible to determine the future of the Universe itself from them as well.

Not bad. A gorgeous galaxy, an exploding star, and an astronomical mystery, plus the awe and wonder we get for free whenever we study the cosmos around us. Observing NGC 4666 is a pretty sweet deal.