Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Two (kinda) Earth-sized rocky planets found around a nearby red dwarf star

Earth-like they ain't, though.

Another nearby planetary system has been discovered! Astronomers have found two Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting a star just 33 light-years from us. That makes this the fourth closest multi-planet system known. And there may very well be more planets there we haven’t seen yet.

The star is called HD 260655, and it’s a red dwarf: a small, cool star in the constellation Gemini. It’s faint, about 1% the brightness of the dimmest star you can see by eye, despite how close it is to us. Red dwarfs are the dim bulbs of the cosmos.

The planets were first detected by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, in November of 2021 [link to paper]. TESS observes stars over and over again looking for small dips in their brightness caused when an orbiting planet passes directly in front of the star, causing a mini-eclipse, technically called a transit. The amount of light blocked tells us the size of the planet, and the timing tells us about its orbit.

In the case of HD 260655 it saw quite a few transits, clearly appearing as two cycles on top of each other: two planets transiting once per orbit. Both caused a less than 0.1% dip in the star’s light, but enough to trigger the automatic software to alert astronomers.

Both planets are only a little bit bigger than Earth: HD 260655 b (the inner planet) is about 1.2 times the Earth’s diameter, and HD 260655 c (the outer one) about 1.5 times our size.

Perhaps more importantly, the masses of the two planets were found as well. This was done by looking at how they affect the star; as they orbit around the star their gravity tugs on it, making it make little circles around their center of gravity, called the barycenter, as well. That can’t be seen directly, but as the star orbits the barycenter it sometimes approaches us and sometimes moves away, so its light is very slightly Doppler shifted.

As it happens, observations of HD 260655 had already been made using the HIRES camera on the immense 10-meter Keck I telescope as part of a survey of bright stars to look for this shift. Using that archived data, the astronomers found that the mass of planet b is 2.1 times that of the Earth, and planet c is 3.1 times heftier.

This is important because with the mass and size of each planet we can find their densities, which is a huge clue into their composition. Planet b has an overall density of 6.2 grams per cubic centimeter, and planet c 4.7 g/cc. For comparison, Earth’s density is 5.5 grams per cc, so these planets are likely very similar to our own composition-wise, meaning they probably have iron cores and rocky mantles.

But are they Earth-like in other ways? Well, no. Like, really no. Planet b takes just 2.7 days to orbit the star at a distance of 4.4 million km from the star, and planet c takes 5.7 days at a distance of a little over 7 million km. That’s close. Despite the star being dim and cool, both planets are cooked by it, and have temperatures hotter than an oven.

A very interesting question is, do these planets have atmospheres? It can be hard for a planet to hold onto air when it’s really hot, but Venus does it. In fact, its atmosphere is far, far thicker than ours, and its surface temperature much hotter even than these two planets. Both of the exoplanets have surface gravity about 30-40% stronger than Earth’s, so they could hold onto quite a bit of gas.

There’s a way to tell. When the planet passes in front of its star, some of the starlight travels through the planet’s atmosphere on its way to us. Different atoms and molecules in the air absorb light at specific colors, and if you take a spectrum of the star that absorption can potentially be detected. This has been done for a lot of big planets, for example, and their atmospheres analyzed.

HD 260655 b and c could potentially be observed this way with JWST, and in fact are ranked very highly by astronomers as possible targets. While their air probably won’t be anything like ours, we don’t know much about the atmospheres of rocky exoplanets. Any observation at this stage would be hugely helpful.

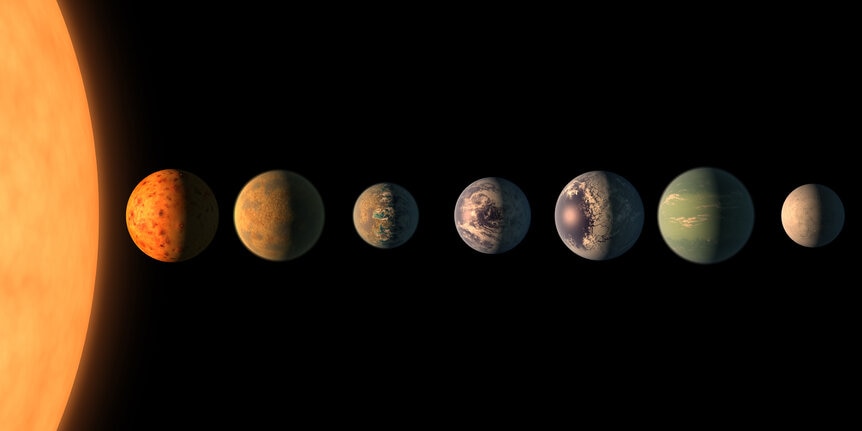

And there’s one more thing that makes this observation so interesting: Red dwarf stars may be dim and low mass, but they’re overachievers when it comes to having small, rocky planets. TRAPPIST-1 is the most famous example; it’s barely bigger than Jupiter and so faint it was only discovered recently despite being only 40 light-years away, yet it has seven Earth-sized planets orbiting it! Three of them are also at the right distance from the star to possibly have liquid water on their surfaces, too.

HD 260655 has two planets that we’ve seen. It could have several more as yet undetected, either too small, too far from the star, or with orbits tipped at too much an angle to be seen via transit at this time. But with two planets known for sure, I’ll just bet astronomers will soon be pointing their ‘scopes at this wee star to see if it has any more secrets to reveal.