Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Frog legs are off the dinner plate and onto the frontier of limb regeneration

That's one small leap for a frog, one giant leap for limb regeneration.

Curt Connors famously became an accidental villain in the Spider-Man canon when he attempted to regenerate a lost limb using lizard DNA. Lizards have always been our go-to model for vertebrate regeneration owing to the well-known phenomenon of tail loss and regrowth, but it might be that we should have put our chips down on frogs.

Michael Levin is a researcher from the Department of Biology at Tufts University who, along with colleagues, achieved an incredible level of limb regeneration in African clawed frogs. Their findings were published in the journal Science Advances.

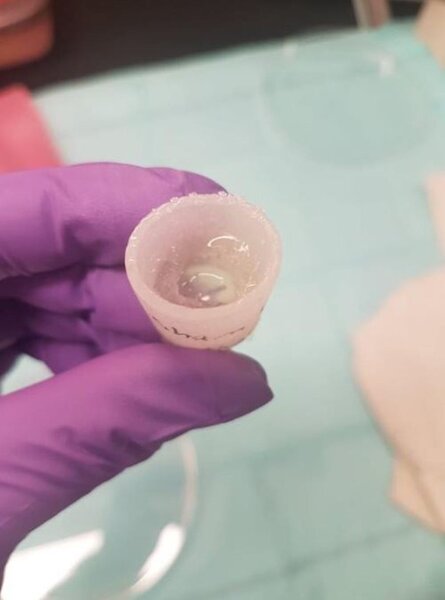

The procedure involves a wearable bioreactor called the BioDome which is placed directly on the amputation site to allow the wound a level of protection from the environment. Inside the bioreactor is a drug cocktail which sends signals to the body stimulating regeneration.

“It’s attached to the animal and stays there for 24 hours. We fill it with a silk-based gel with a drug cocktail mixed in. After 24 hours we take it off and we watch the animals do their thing,” Levin told SYFY WIRE.

African clawed frogs aren’t known for any particular regenerative ability. They have a similar capacity for healing as we do, and that’s precisely why the team chose them. Previous experiments have used froglets — immature frogs — who may have retained some of the regenerative ability which comes with development and metamorphosis. In this study, only adults were used in order to ensure there was no latent ability for regrowth.

This strategy for regeneration is novel in the way it works. Every animal’s body knows how to create complex structures at least one time, otherwise we wouldn’t develop in the womb or the egg, but for many vertebrate species it’s a one-time deal. If you lose a complex structure after it has been built, there’s no getting it back. Other studies have used stem cells as a way to get the body to revert to that initially flexible state and regrow structures. The BioDome, with its drug cocktail, does something simpler and potentially more elegant.

We are interested in identifying triggers, we don’t want to micromanage the process,” Levin said. “We want to find upstream signals which tell the body to build whatever goes here. We’re not going to tell it how to do it or how it’s made, because we don’t know. We’re going to provide a signal that pushes the cells to do it.”

That’s what the team’s protocol does. The drug cocktail, made of five different components, reduces swelling and scar formation while stimulating the growth of new tissues. In the studied frogs, this brief initial intervention was enough for their bodies to construct a whole new limb over the course of several months.

As with most medical treatments, there was some variability in the results. Levin tells us that some animals had a moderate response while others reconstructed nearly complete limbs. Yet, even the best legs weren’t fully complete. They were missing the long toes at the end of the foot and the webbing. It’s worth noting that the incomplete reconstruction might have been the result of when observation stopped, and if the frogs were given more time, they might have finished the job.

“They were not cosmetically perfect,” Levin said. “In other ways they were very good legs. They were fully functional. The animals were using them to get around and standing on them, and they were touch sensitive at the very tips.”

More promising perhaps, than even the results of this study, is the fact that this drug cocktail was the team’s first at bat. Many times, new therapies take dozens or hundreds of derivations before landing on one which works. That wasn’t the case here.

“This was our first guess. I’m hopeful that if this is what our guess looks like, the optimized cocktail will be way better. It’s got to be. There’s no way we happened on the best one the first time out of the gate,” Levin said.

The bioreactor and drug cocktail also has the potential for applications elsewhere in the body, regrowing other limbs and tissues, including internal organs.

“None of the things we did were limb specific. We didn’t have anything in the cocktail that was specific for making legs. It’s a very general kind of trigger that says build whatever goes here. We have great hopes that this is ultimately going to address all sorts of regenerative needs,” Levin said.

All that being said, there’s still a lot of work to do answering a lot of basic questions about the process of regeneration before it’s ready for prime time in human patients. The team is currently doing experiments in mice and will later move into larger mammalian models, though they haven’t yet determined what those will be or when they’ll take place.

It’s early days, but these results are promising. With any luck, we’ll have a reliable process for the regeneration of complex tissues without the risk of becoming a humanoid reptile bent on destruction.