Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The loneliest robot on Earth is investigating the ocean carbon cycle

Someone please send it some friends!

It’s been famously said that we know more about the solar system than we do about our own oceans, and that’s true by many objective measures. We specifically have a poor understanding of the carbon cycle of the deep oceans, something which is increasingly important under the continued impact of anthropogenic climate change.

Station M, a name which conjures images of science fiction heroics happening in the deep, is an observation station in the northeast Pacific where scientists are in the process of an ongoing time series study of the oceanic carbon cycle.

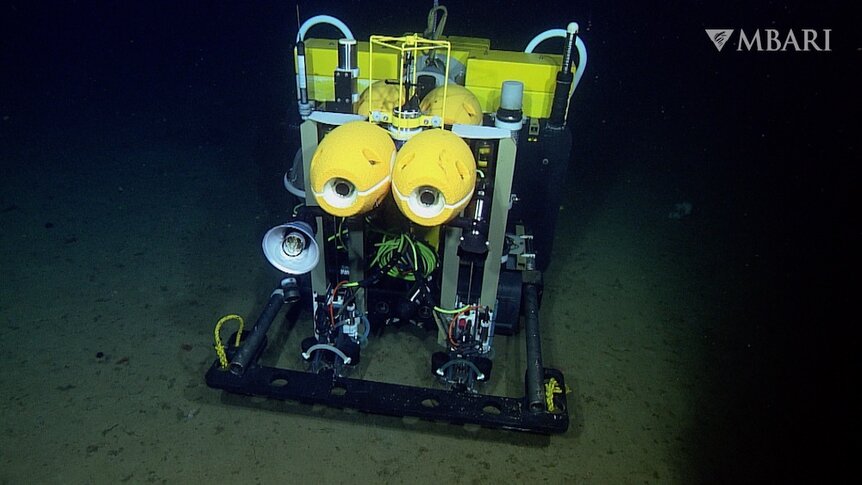

That study previously relied on periodic measurements of marine snow (organic materials including dead plants and animals, as well as animal waste) and sequestered carbon in marine soil on the seafloor, but over the last several years it’s gained a new tool allowing it to acquire more robust and more complete measurements in the shape of an adorable little rover known as Benthic Rover II (BR-II)

The rover operates at a depth of 4,000 meters below the surface and remains submerged for a year at a time, where it takes continuous measurements of oxygen concentration and consumption. The first couple years had a series of drawbacks as researchers overcame hurdles in the rover’s operations, but for the last five years it has operated almost non-stop measuring the deep waters of the Pacific.

Crissy Huffard, senior research specialist and Alana Sherman, electrical engineer, both at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, along with their colleagues, have been working with BR-II for more than fifteen years, unraveling the secrets of how carbon makes its way into and out of deep waters.

“One of the big questions is how much carbon makes it into the deep sea where it might be sequestered away from the atmosphere, and what happens to it once it gets there. We can’t just assume that it all makes it magically into the sediments for long-term storage, so the rover has helped us fill in one of the really important pieces of that puzzle, which is how much gets consumed by sea-floor communities down there,” Huffard told SYFY WIRE.

Getting to this point took a lot of hard work, problem solving, and engineering. The deep oceans, calm as they might be, are not exactly friendly to humans or their machines. There are certainly challenges to getting a probe or rover into space, but pressure isn’t one of them. In the ocean, the pressure increases by roughly one atmosphere for every ten meters down, so BR-II lives with nearly 400 times the pressure we experience bearing down at all times. Getting down there at all meant it had to be built tough, let alone staying for a year at a time.

“We used different approaches to deal with the different challenges of the environment,” Sherman said. “You can get away with a lot if you’re just dunking in the water for a few days, but not for long time periods. Almost the entire rover is either titanium or plastic. The amazing thing is it will be deployed for a year, and it comes to the surface looking like it just came out of a carwash. Almost all of the electronics are in spherical titanium housings that remain at one atmosphere.”

It’s tough enough that BR-II is rated for depths significantly lower than where it usually resides, and could likely stay down significantly longer if not for a few technological limitations. The batteries are large and must be kept inside those special pressurized titanium spheres. There’s enough onboard energy to run BR-II for about 13 months, after which it needs to surface for recharging. The team opts to surface the rover every 12 months in order to keep to a schedule. If they didn’t, the surface date would shift around the calendar each year, requiring them to be at sea during times which are less friendly than the autumn months.

The rover was initially designed without any communications abilities. It descended to the depths where it would take photos and environmental samples, storing the data for retrieval at the end of each deployment. It’s equipped with sampling instruments which capture seafloor water and sediment and measure them using an oxygen sensor. That sensor measures oxygen drawdown inside the chamber, which allows the team to calculate carbon consumption. The photos it takes also provide information about the levels of chlorophyll on the seafloor as well as the animal populations living in the immediate area. All of that data combined paints a picture of the health of the environment and the way it changes over time.

Since its first deployment, the challenge of communication has improved somewhat, by virtue of Wave Glider, developed by Liquid Robotics. This machine, which looks like a cyberpunk surfboard, makes period visits to the surface above BR-II and communicates acoustically with the vehicle through 4,000 meters of water. The rover can send status updates to the Glider, but those aren’t always necessary.

“The Wave Glider can go out on its own and talk acoustically to the rover,” Sherman said. “But we learned if we had the Wave Glider triangulate the rover’s position, just by knowing where it was supposed to be, that told us most of what we needed to know. Any time it’s where it’s supposed to be, it’s probably doing what it’s supposed to be doing.”

Huffard added, “It helps us be a lot more efficient with our ship time. Once we do get onto station, we know exactly where to go. Or, if we don’t know where to go, we know to budget time in our schedule to look.”

Station M also has other instruments which measure the marine snow falling to the seafloor and how much carbon is contained inside it. That data, coupled with the consumption information BR-II provides, help to paint a more complete picture of the whole carbon cycle. Having continuous measurements of carbon movements from the surface to the seafloor are critical to understanding the way carbon travels within the largest ecosystem on our planet.

“For the first 20 years of the project, it seemed like Station M was carbon limited and there wasn’t as much carbon coming down as was being consumed. We’re seeing a big increase in the marine snow coming down over the last 10 years. It’s coming down in these huge flux events that might only last a few weeks or a month, but it can be years’ worth of carbon. Now there are periods of excess and that can be stored in the sediments,” Huffard said.

These massive marine snowfalls are exceedingly difficult to predict. Seasonality on the surface plays a part in their variability as phytoplankton and other marine plants and animals produce more or less organic materials season by season. The interactions of storm systems and mid-water animals further complicate the system causing huge swings in production month over month and year over year. Huffard and Sherman are imagining ways to improve the technology or use it more symbiotically to capture these events as they’re happening.

“We have other instruments that are looking at all the marine snow coming down that can actually sense when these big events are happening. Because we have acoustics on those instruments and on the rover, there could be communication which would allow us to change the way we sample and image during these high-flux periods,” Sherman said.

Huffard added, “Event detection and the ability to respond in the context of an entire suite of autonomous instruments is really where a lot of our goals lie.”

Because of all the variability in carbon production and sequestration, robust long-term measurements are needed in order to truly understand the role the oceans — and our ocean-dwelling non-human neighbors — play in natural carbon storage.

Given the success of BR-II, we might do well to send it some friends. More fully understanding the secret workings of our planet is likely to our benefit. It’s the only one we have.