Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

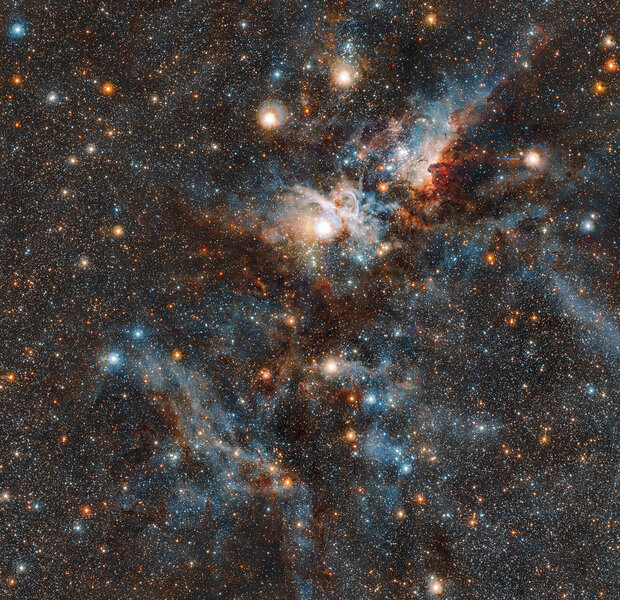

Carina’s star-spangled chaos

You can think of our galaxy as being like a city, a bustling metropolis with hundreds of billions of stars in it. In a human city, people being people and all, you need to have nurseries. Galaxies too: Stars have to come from somewhere.

Where they come from are nebulae, clouds of gas and dust. These exist by the hundreds in the disk of the Milky Way. Some are small, some are big, and some are colossal.

If you look toward the constellation of Carina, you can see one of the galaxy’s busiest nurseries: the Carina Nebula.

7,500 light years away and a mind-crushing 300 light years — 3,000 trillion kilometers — across, it’s the site of thousands of stars being born. The amount of gas available is something like a million times the mass of the Sun*, so it has plenty of raw material to make stars for a long, long time.

Some of those stars are so massive and bright that they can easily be seen from other galaxies, so finding them isn’t so hard. The fainter ones, though, can be hidden behind thick clouds of dust. One way to get around that is to observe the nebula in the infrared; this flavor of light more easily passes through the dust clouds, allowing the lower-mass, dimmer-bulb stars to be spotted.

Astronomers used the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy camera on the Very Large Telescope Survey Telescope in Chile to do just that, and the result is…. Well, the result is WOW.

Yeah, seriously. This image is stunning, and huge. I had to shrink it considerably so you could download it in a reasonable time and not kill our servers, but the full-resolution shot is 140 million pixels, and covers an area of the sky well over a degree across (the Moon is half a degree wide).

The sheer number of stars in this image is staggering. I grabbed a random section of it that was 100 x 40 pixels (so, 4000 pixels in total) and counted 40 stars in it. Extrapolating wildly from that single stat, the 140-million-pixel image should have about 1 million stars in it.

A million. Yegads. Mind you, not all those are in the Carina Nebula! We’re looking through our galaxy for thousands of light years to see the nebula, so there are plenty of stars between here and there. But still. Dang. That’s a lot of stars.

The astronomers can use this image to look at these stars, examine their colors, and determine (for the most part) which ones are in the nebula and which aren’t, thus taking a census of the stars in it. It’s not easy to do this for low-mass stars, so we don’t really know how many of them are made compared to the more massive, more obvious stars, so this work will help us understand better how stars are born.

The colors you see here are not what you’d see with your eye, since it’s all infrared. What’s shown as blue is actually 0.88 microns, or a wavelength just outside what your eye can see. Green is really 1.25 microns and red is 2.15, so both are well into the near-infrared.

Even in the infrared, a lot of gas and dust still are visible. That’s because there’s a whole bunch of it here. And it’s not just randomly strewn around; patterns are there when you look for them.

For example, in this subimage you can see long, skinny triangles of dust. These are formed when very thick clots of dust are near very luminous stars. The wind and fierce blast of ultraviolet light from the stars erode away at the clump and also flow around it. They’re like sandbars in a stream! This is the same mechanism that made the Pillars of Creation in the Eagle nebula, and they’re common in star-forming nebulae.

You might also get a kick out of comparing this image with one taken a few years ago using the HAWK-I camera on the Very Large Telescope†. The HAWK-I shot is smaller, showing only the top part of the VISTA image, but they’re both infrared, so some of the same features are there. Incidentally, the brightest part of both images is the chaos around the ridiculous star Eta Carinae, a monster star that’s actually two stars orbiting each other. The primary is something like 100 times the mass of the Sun (!!!) and is so luminous that if it were any more energetic it would tear itself apart. The secondary is probably a mere 30 times the mass of the Sun… which itself would be considered a beast if it weren’t orbiting the colossal primary.

And even that isn’t the most luminous star in the nebula. That honor goes to the lower-mass star WR 25, which nonetheless blasts out several million times the energy the Sun does. And in a short time — oh, say a million years or three — it’ll explode, and then we’ll really see something. It’ll be brighter than Venus in the sky!

You know what? I’m rather glad this stuff is all 75,000 trillion kilometers away. It’s gorgeous, but holy yikes. We're close enough to study it but far enough not to get fried by it. I'm good with that compromise.

*Just writing that number down made several hundred of my synapses snap shut in self-defense.

†This is confusing, I admit. The Very Large Telescope is actually made up of four 8.1 meter “unit” telescopes, and are sometimes considered as a group. Then there’s another, smaller 2.6 meter 'scope which was designed to have a wide field of view to do surveys, so it’s called the VLT Survey Telescope, or Very Large Telescope Survey Telescope (maddeningly abbreviated VST). The nomenclature is awful. I hope they don’t put up another ‘scope as an adjunct to the VST. What would they call it?