Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Raise the roof: Climate change is elevating the lower atmosphere

It might be time to end this particular party.

What we think of as the atmosphere is broken up into three main layers; the troposphere which is where we live and where weather systems largely take place; the stratosphere, where the ozone layer resides; and the mesosphere, which stretches to about 50 miles (80 kilometers) above the surface. The following layers, the thermosphere and exosphere, are so sparse and so large we often don’t think of them as being part of the atmosphere. The International Space Station orbits in the thermosphere, and the exosphere extends for thousands of miles.

Between each layer is a boundary where conditions — namely temperature — shift pretty radically. When you were in school, you probably learned that each layer extended to a particular height before giving way to the next, but that’s changed and is continuing to change, mostly due to human-caused climate change.

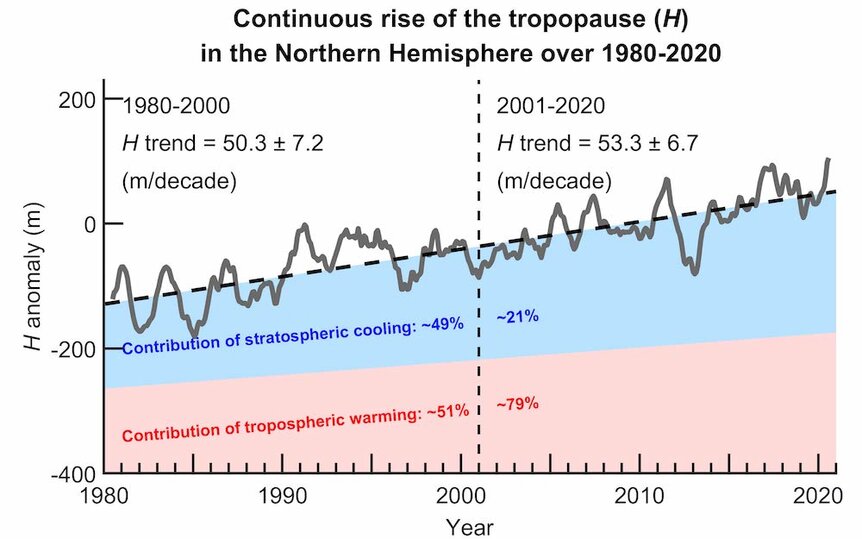

A new paper by Jane Liu from the Department of Geography and Planning at the University of Toronto, and colleagues, describes how over the last several decades the tropopause (the boundary between the troposphere and stratosphere) has been on the move, consistently climbing at a rate of 50 to 60 meters per decade. Their findings were published in the journal Science Advances.

“The cause of atmospheric rising is complex,” Liu told SYFY WIRE. “As you climb to higher altitudes the temperature decreases at about 6.5 degrees per kilometer until you reach the tropopause. As global temperatures increase, the height of that boundary also increases.”

The troposphere and stratosphere interact with one another, exchanging gases and water vapors. In prior decades the system was complicated by the depletion of the ozone layer as a result of CFC usage. The stratosphere was shrinking while the troposphere rose.

Previous troposphere measurements containing data from 1980 through 2000 saw a consistent increase in the height of the tropopause, but there were conflicting models about what might happen after that time. Some models suggested the height increase would continue apace; others suggested it might slow down as the ozone layer rebounded.

This new study takes data from balloon measurements and satellites to construct an updated view, focused primarily in the Northern Hemisphere, of tropopause height from 1980 to present. It confirmed the revitalization of the ozone layer was not sufficient to halt tropospheric rising. In fact, the per-decade average increase has sped up slightly from 50.3 meters per decade with a 7.2 meter margin of error, to 53.3 meters per decade with a 6.7 meter margin of error.

“We launch balloons over land and measure temperature, pressure, and humidity. The instruments send a signal back to the receiving station until they burst. There are other factors which can cause a rise in the tropopause. Weather systems and volcanic activity can cause temporary fluctuations for two or three years, but it’s very small in the long run,” Liu said.

Researchers corrected for natural fluctuations which might temporarily and moderately impact the height of the tropopause. Those effects could only account for a fraction of the change over the last several decades, leaving about 70% of the total height increase explainable only by anthropogenic climate change.

The good news, if we can call it that, is that the rise in the troposphere’s upper boundary will likely have little impact on our lives here on the ground. Researchers believe weather systems shouldn’t be measurably changed by this specific factor. Though, the long-term impacts of atmospheric rising are unknown and the subject of continued research.

“We’d like to further investigate, in collaboration with scientists around the world, height variation over the Southern Hemisphere and see what the long-term consequences of troposphere change are,” Liu said.

Until that research is completed, tropopause height serves as a reliable indicator of overall warming, rising in much the same way as mercury in a thermometer. The atmosphere is incredibly, almost imperceptibly big, and can probably take a little beating. But we only have the one, and messing with it is maybe not the best idea.

It might be beyond time for us to cool it.