Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Crash site of the Apollo 12 ascent module possibly found after almost 50 years

After almost five decades, it looks like the final resting place of a missing piece of historic space hardware may have been found: A very odd set of lunar features could mark the location where part of the Apollo 12 Lunar Module slammed into the Moon at nearly two kilometers per second.

This’ll take a wee bit of explaining.

The Apollo 12 Saturn V carrying Al Bean, Pete Conrad, and Dick Gordon launched on November 14, 1969. Four plus days later, the Lunar Module carrying Bean and Conrad dropped down from lunar orbit to the Moon’s surface and landed on November 19. The astronauts spent over a day on the Moon, then returned to Earth on November 24 after a highly successful mission.

While on the Moon, they deployed a series of instruments called the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package, or ALSEP. One of these experiments on it was the Passive Seismic Experiment, designed to detect moonquakes. These tremors can be caused by meteorite impacts, possible volcanic activity, landslides… or they can be created on purpose, by humans.

How did NASA make an artificial moonquake? By crashing a no-longer-needed Apollo vehicle into the Moon.

There were two vehicles that astronauts used to get down to the Moon, back up, and then back to Earth. Moreover, each of these was composed of two separate pieces of hardware.

The Command and Service Module (or CSM) made up one of these pairs; the Command Module was the familiar cone-shaped capsule that came back to Earth and splashed down in the Pacific, and the Service Module was the cylindrical contraption behind it with the propulsion system (rocket and fuel). This is what carried the astronauts to the Moon, slowed them to enter orbit, and carried them home.

Attached to it in the front was the Lunar Module (or LM), the insect-like vehicle that went down to the Moon and back. This in turn was made up of the Descent stage and the Ascent stage. The Descent stage (the bottom half with the legs) had a rocket powerful enough to drop the LM down to the Moon’s surface, but was no longer needed after that and was dead weight. So to save fuel it was left behind, with the Ascent stage (the upper part) carrying the two astronauts back up to orbit to meet up with the CSM and the third astronaut (Gordon), who had remained on the CSM in orbit during the landing mission.

Once the moonwalkers got back on board the orbiting CSM, the Ascent stage was no longer needed. Now this is the clever bit: It detached, and the remaining fuel was used to deorbit it and crash it near the landing site, so that the seismometer could measure the impact. Artificial moonquake!

It was supposed to hit about 10 kilometers from the landing site, but wound up performing the deorbit burn for longer than expected, and crashed much farther away. The problem is, no one knew where.

Until now. A pair of scientists may have finally found the impact site.

They searched through images taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been creating phenomenal high-resolution maps of the Moon’s surface for years now. They didn’t have to look at the entire Moon since — from the length of the deorbit burn — they knew the crash site was within 80 or so kilometers of the original landing site, so they focused on that area. The two authors searched images individually, without consulting each other, so they could be independent and not bias each other. In fact, one of them found the images in question in 2013, and the other in 2016. After that, they worked together on what they saw.

[Note: I want to be careful here and say that the claims of this being the impact site of the Ascent stage are compelling, but not yet confirmed. So when you read below about the impact site, put an understood “alleged” in front of it.]

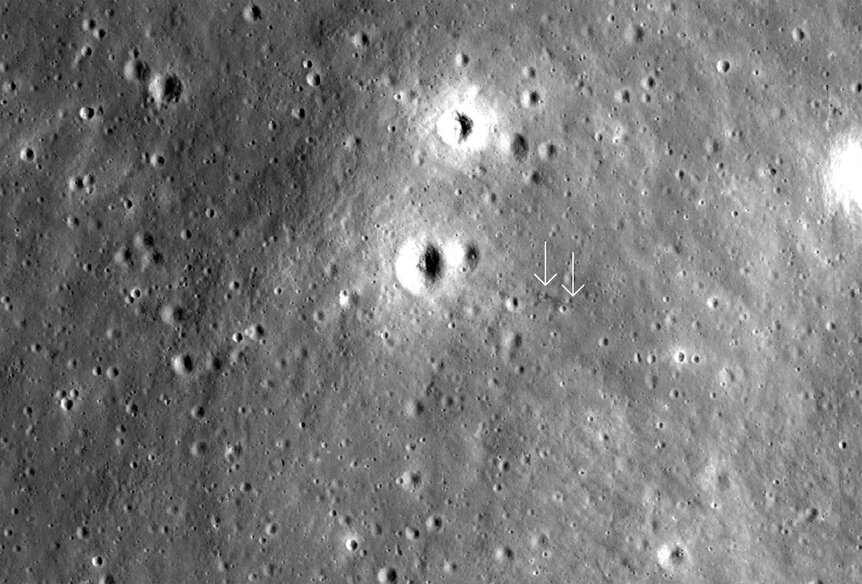

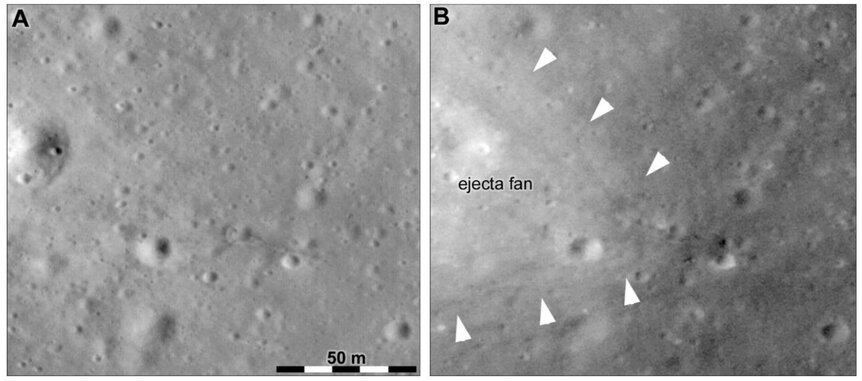

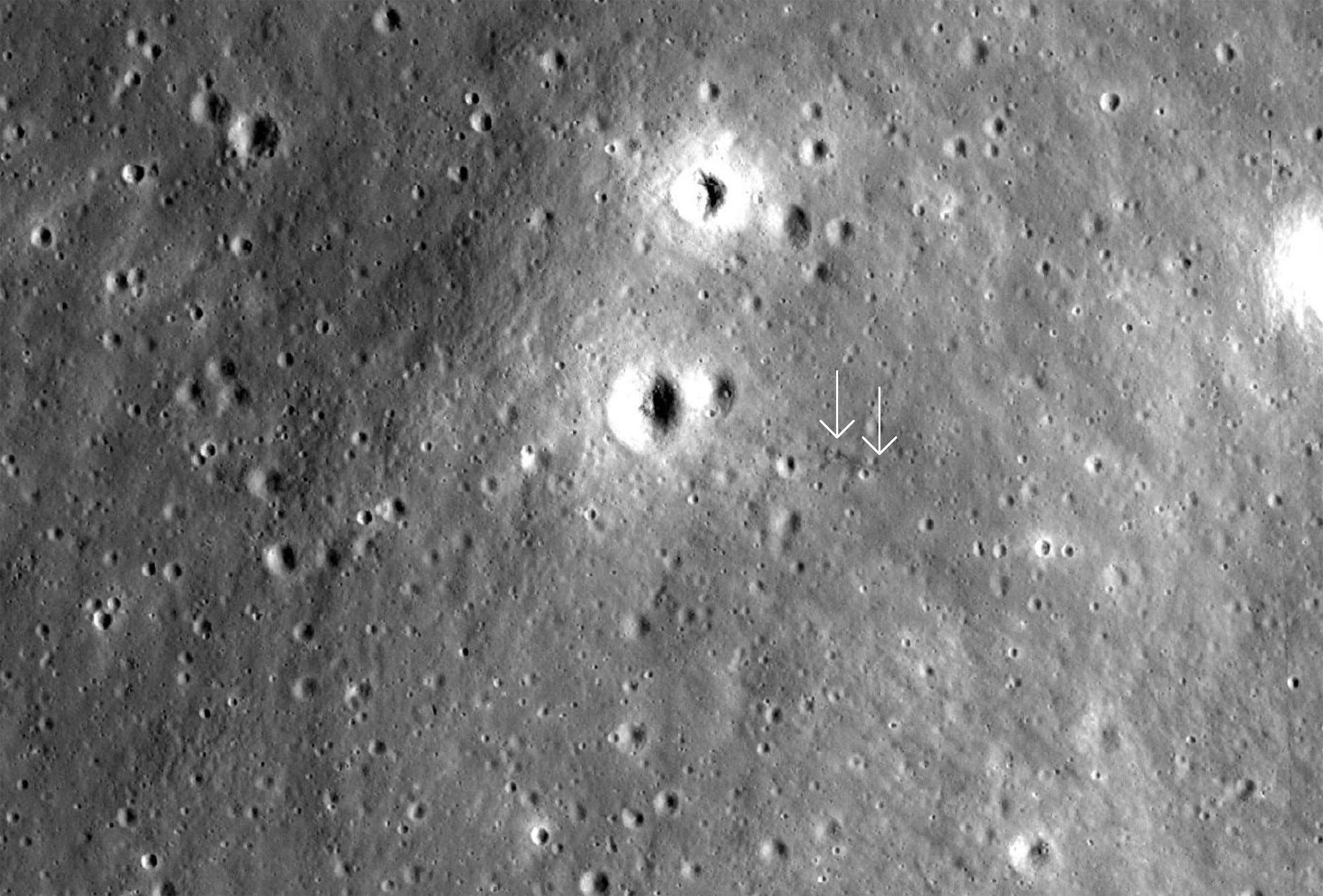

They think the impact site is at a lunar latitude and longitude of 3.920° S, 338.828° E (click that for a pan-and-zoomable map of that area). They found a dark streak on the surface that matches the trajectory of the Apollo 12 Ascent stage (roughly west by northwest, so mostly right to left but also a little upwards). The streak is about 30 meters long and 4 meters wide, a little bit narrower and longer than a tennis court.

That’s consistent with what’s known about the impact of the Ascent stage. It was moving at roughly 1.7 kilometers per second (about twice as fast as a rifle bullet) and the impact angle was extremely shallow, about 4° from horizontal. That should leave a furrow or trough dug into the surface.

Processing the image to bring out features, they also spot what looks like a fan of debris blown out by the impact, which also has the correct orientation. Given that the Ascent stage had a mass of nearly 2,400 kilograms, that makes sense too. It would’ve hit hard.

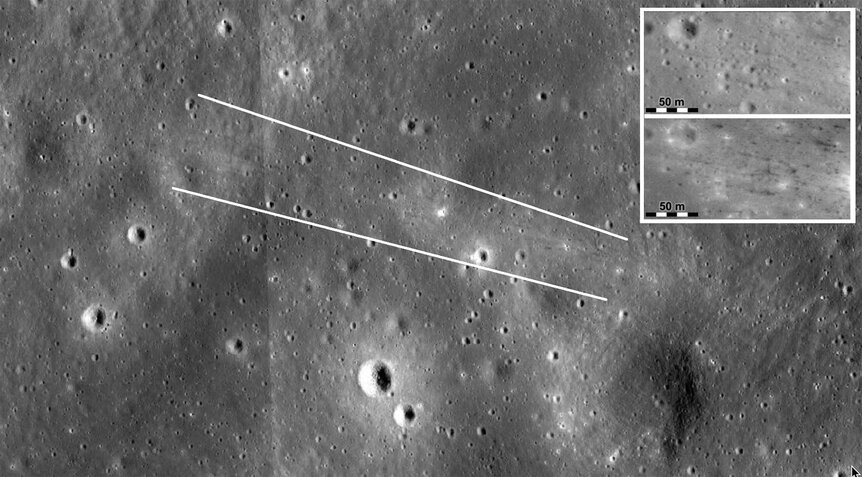

On its own that would be interesting but not necessarily convincing. But they followed the direction of the impact trough to the northwest, and found a series of dark streaks that run parallel to the impact mark, starting about 100 meters to the west-northwest and running for almost 2.5 km! They interpret this as material blown out by the impact that flew downrange, traveling quite some distance due to the low gravity and lack of air resistance.

That’s a lot more persuasive. And it gets better: Looking at the topography, they found these streaks on the sides of slopes facing the impact site, but not on the slopes facing away. That’s exactly what you’d expect for debris blasted out and settling on the surface. Something moving ballistically is unlikely to land on the far side of hill, and far more likely to hit on the near side of it.

So, case closed? Well, no. I do have some reservations with the claims. In the wide impact site image I first displayed, there are some other streaks below and to the left that roughly parallel the impact furrow. I don’t know what they are, but their alignment is worrisome. The impact streak is the darkest of all of them, but that doesn’t mean it really was where the impact site was.

Also, some of the later Apollo missions also underwent this same process of de-orbiting the Ascent stages and letting them hit. In no other case were those downrange streaks seen. That’s not necessarily damning; perhaps Apollo 12 was a special case, and something happened with it to create those streaks, whereas it didn’t happen with the other missions. That’s not a great argument without evidence — it’s not good to resort to special pleading. But it’s not totally out of the question, either; there weren’t that many missions, so we don’t have a lot of examples, and they all hit in different places with different geology, so one site being weird isn’t that silly.

In my opinion they make a strong case, and if I had to bet I’d say they’re right… but I’d also like to see higher-resolution images of the site before making up my mind.

Incidentally, they’ve been looking at the Ascent stage impacts of the other missions as well, and it’ll be interesting to see those, too. Maybe they will provide more insight into this impact.

With the recent announcements of so many different private companies and governments saying they want to go to the Moon, I expect it won’t be too much longer before we have a lot more information about the Moon. We’ll be seeing the Apollo sites better than we have since, well, Apollo. Hopefully a lot of lingering questions will be answered, and soon.

Tip o' the spacesuit helmet to my old pal Dan Vergano who tweeted about the paper.