Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Desktop Project Part 19: Infrared Orion

[Over the past few weeks, I've collected a metric ton of cool pictures to post, but somehow have never gotten around to actually posting them. My Desktop Project -- posting one of those pictures every day -- is my way of clearing off my PC's desktop, and also showing you some truly amazing stuff. Enjoy!]

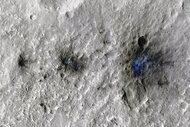

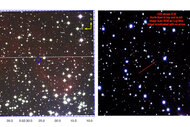

The Orion Nebula is a perennial favorite for astronomers. It's big (the size of the full Moon on the sky), bright (visible to the naked eye), and gorgeous (even binoculars show some wispy details). It's also scientifically fascinating, since it's the closest example of a big star-forming factory in the Milky Way. We get a fantastic view of it and can study it in incredible detail (see Related Posts below for lots more pix).

Because of all that, it amazes me that anything can provide a truly new view of this old friend... but then our eyes don't see into the deep infrared. When you combine images taken with the Herschel and Spitzer space telescopes, which probe the cosmos in that part of the spectrum, the portrait they make is just stunning:

[Click to ennebulenate.]

As lovely as this picture is, there's an important science story going on here as well. The stars you see embedded in those filaments and knots of interstellar material are actually very, very young: probably only a few million years old, and on the verge of becoming full-fledged stars like the Sun. They're still enshrouded in the dust and gas disks in which they formed. Near the embryonic stars, of course, the dust is warmer, and farther out it's colder. Spitzer and Herschel see in different parts of the infrared, where the different temperatures of dust emit light, so they probe both the inner and outer parts of the clouds.

Astronomers used Herschel to observe this nebula in 2011, taking a series of images over time. What they found is that the stars and their dust changed in brightness by as much as 20% very rapidly -- over weeks, when it would be expected to take years! It's not clear what's going on behind this variability. I suspect the disks of material around the stars are clumpy, and the inner region has clouds that block the starlight, shadowing the outer region. As that happens, the cooler part of the disk dims, which is what Herschel saw. Other processes may be at work as well, but any ideas as to what they are have to be tested against the observations.

Which is precisely why we observe even familiar objects with telescopes sensitive to different kinds of light. Ultraviolet, infrared, visible, radio, X-ray -- these are all parts of the spectrum controlled by different processes, so by observing different flavors of light we see the different engines creating them. It's the combination of these varying views that gives us insight (literally, in this case, since we're seeing inside a nebula!) into the physical mechanisms of various astronomical phenomena.

Even though the Orion nebula is one of the best studied objects in the sky, there's still a lot to learn from it. And as long as we keep our eyes open, especially across the electromagnetic spectrum, then more and more of its secrets will be revealed.

Image credit: ESA/NASA/JPL-Caltech/N. Billot (IRAM)

Related Posts:

- Orion's got cavities!

- A dragon fight in the heart of Orion (this is really awesome)

- Spitzer sees star spew spurious spouts

- A new old view of an old friend