Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Primates' behavioral flexibility helped them survive dino-killing asteroid

Primates had a sort of open relationship with trees

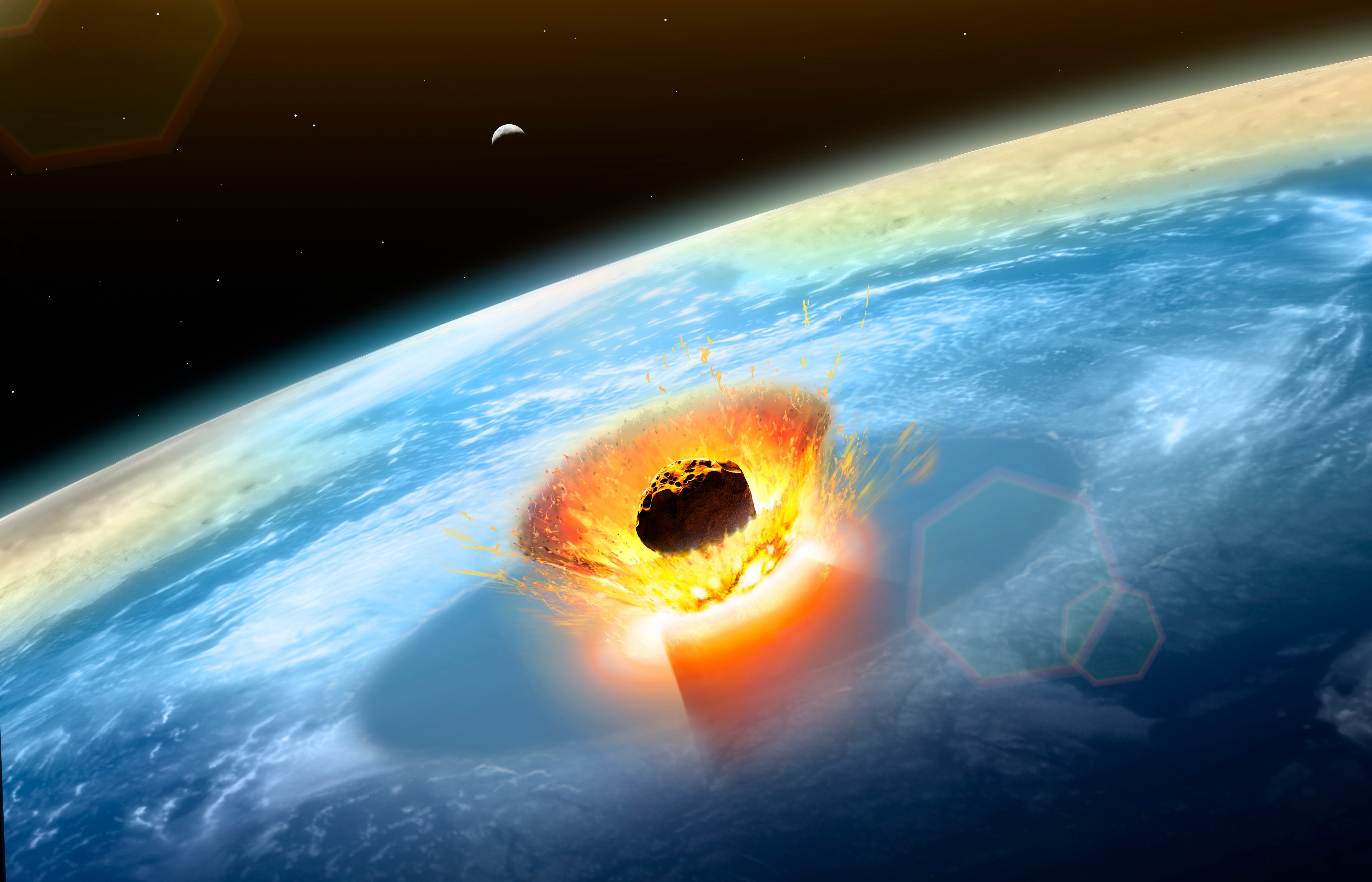

The world looked very different 66 million years ago. The asteroid which impacted at Chicxulub in what is now the Gulf of Mexico caused the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction, wiping out an estimated three quarters of all life on Earth. It certainly was the end for the dinosaurs and could have ended us before we even got started, if not for a few scrappy primates. A recent study by Jonathan Hughes of the Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at Cornell University and colleagues describes the way preferred habitat impacted who survived in the years following the event. Their findings were published in Ecology and Evolution.

The asteroid impact was violent, wiping out a huge number of animals instantaneously, but the real damage happened in the aftermath. Models of the hours following the impact suggest a massive amount of debris was blasted into space before coming back down. As ejecta made its way through the atmosphere on its way to the surface, it generated heat, bathing the planet in infrared radiation.

The heat was enough to bake survivors on the surface and start a series of global wildfires which wiped out most of the plant life, erasing arboreal habitats. “We find a big layer of soot at around that time of the K-Pg extinction, when we look back through the geologic record that seems to be from largescale burning of organic matter,” Hughes told SYFY WIRE. “The primary evidence is longstanding research looking into different types of seeds and their abundance throughout the fossil record. There’s a lot of seeds from trees in the cretaceous that disappear right at the boundary and never return.”

As a result, any animals which had previously lived primarily in trees, suddenly found themselves without a home. In turn, most of those species quickly died out, leaving those non-arboreal species — those living in aquatic environments, on or under the ground, or in cave systems — to repopulate the planet.

Determining precisely what happened to mammal species at the K-Pg boundary has proven difficult, primarily because the fossil record is sparse around the event. “It feels strange that there were lots and lots of things going extinct very quickly and yet very few fossils of them,” Hughes said. “The difficulty for us isn’t just that there aren’t very many fossils, but the ones that exist are very fragmentary.”

To get around this problem, the team used ancestral state reconstruction, starting with modern mammals and working backward to figure out which species were arboreal, semi-arboreal, or non-arboreal. The findings support a strong pressure against those species which were strictly arboreal prior to the extinction event.

Primates, however, despite being arboreal, managed to persist through the extinction event without losing their arboreal adaptations. This suggests that primates were behaviorally flexible. While they may have preferred trees as their primary habitat, they were capable of surviving in their absence.

A review of the flora which existed post K-Pg shows a preference for plants like ferns, for the next thousand or several thousand years. That’s long enough to cause extinction among species which absolutely depend on trees to survive, but short enough that flexible species like primates were able to hang on to their arboreal traits until trees re-emerged. “The lack of trees was a huge selective barrier for arboreal animals, the majority of which seem to have gone extinct. Primates are a weird exception where we’ve reconstructed them as arboreal at the time, yet they persisted,” Hughes said.

In a strange way, the K-Pg extinction and the global wildfires which came along with it, may have been a net positive for primates. Their ability to survive while maintaining their tree-loving characteristics allowed them to swoop in on newly available niches when trees returned a few-thousand years later.

Many of Earth’s surviving species persisted due to winning the evolutionary lottery, falling within those niches which were less-heavily affected by the asteroid impact. The evidence suggests, however, that primates weren’t among those groups. Instead, they were flexible enough to adapt to a rapidly and violently changing environment until such time as their preferred hangouts could be rebuilt.

Those early primates, having survived one of the most catastrophic events in the history of the planet, had an opportunity to sample the ground which would become the home of some of their descendants, millions of years hence.

Now, it’s our job to ensure we don’t have another Chicxulub. We might not be so lucky a second time.