Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Dwarf galaxies have supermassive black holes, too… and some are off-center!

As I've written about many, many times in the past, we think that all big galaxies have supermassive black holes in their centers. These black holes can have up to billions of times the mass of the Sun, and almost certainly formed at the same time as the galaxies themselves.

But there are also dwarf galaxies out there, ones that are much smaller and much lower mass than, say, the Milky Way. In fact, our galaxy is orbited by dozens of dwarf galaxies, and dwarfs are almost certainly the most common kind of galaxy in the Universe (for a given kind of object, Nature tends to make lots of little things and fewer big things; break a rock with a hammer to see this effect in action).

So do dwarf galaxies have supermassive black holes? And if so, what can we learn from them?

Very few dwarf galaxies are known to host these monsters; a likely one was found in 1989 and another in 2004. In 2011, astronomers discovered a supermassive black hole (with a mass of about one million suns) in the nearby dwarf galaxy Henize 2-10.This galaxy is only about 3,000 light years across, so while the black hole is pretty lightweight as such things go, it matches the low mass of the galaxy itself.

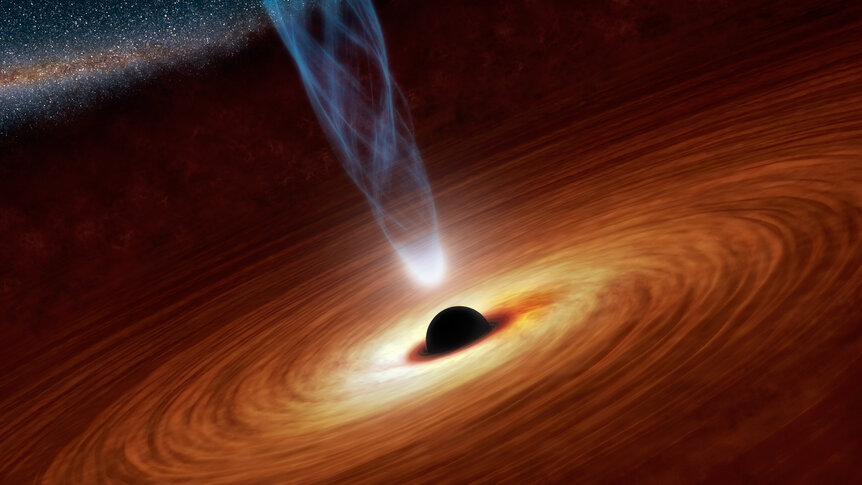

The central black hole in Henize 2-10 got those astronomers thinking. It's blasting out radio waves and X-rays, meaning it's voraciously eating material around it (this material forms a disk as it falls in, and that disk gets incredibly hot, emitting light across the electromagnetic spectrum). Galaxies like this are called active galaxies. Could there also be more active dwarf galaxies, and could black holes be found by looking at dwarf galaxies that are also very bright in radio wavelengths?

So they set about looking for them. Using various techniques, they culled a huge list of over 43,000 galaxies (!!) down to just a few dozen (the galaxies needed to be small, with less than 3 million times the mass of the Sun; they had to be bright in radio waves; they had to have compact radio sources in them because the region around a black hole emitting radio waves is small; and so on). This process went on until they were left with 111 galaxies they could examine.

They used the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array, a collection of radio telescopes in New Mexico, to observe these galaxies. Some didn't have supermassive black hole sthat could be found, but were emitting radio waves because of big gas clouds, expanding debris from supernova explosions, and other objects which look like feeding black holes.

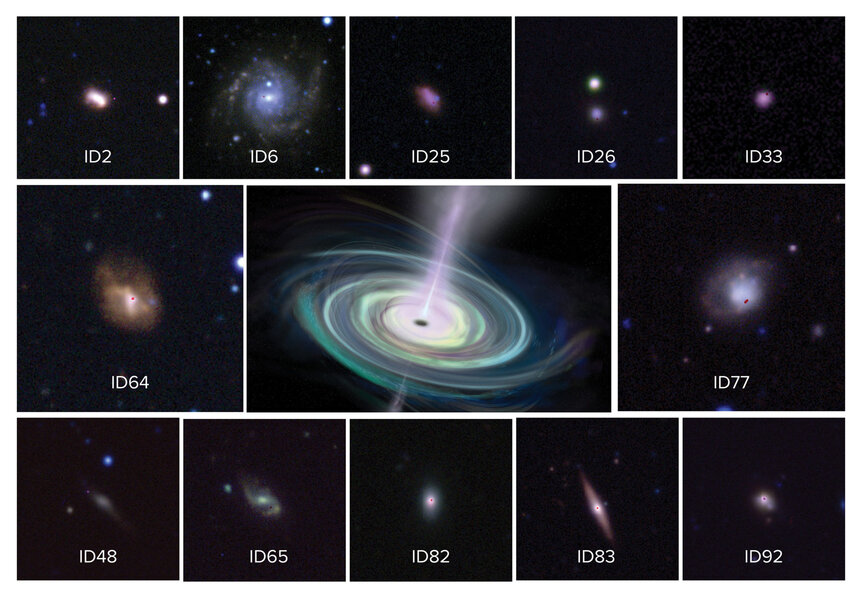

But finally, in the end, they had what they were looking for: 13 dwarf galaxies they could confidently classify as active.

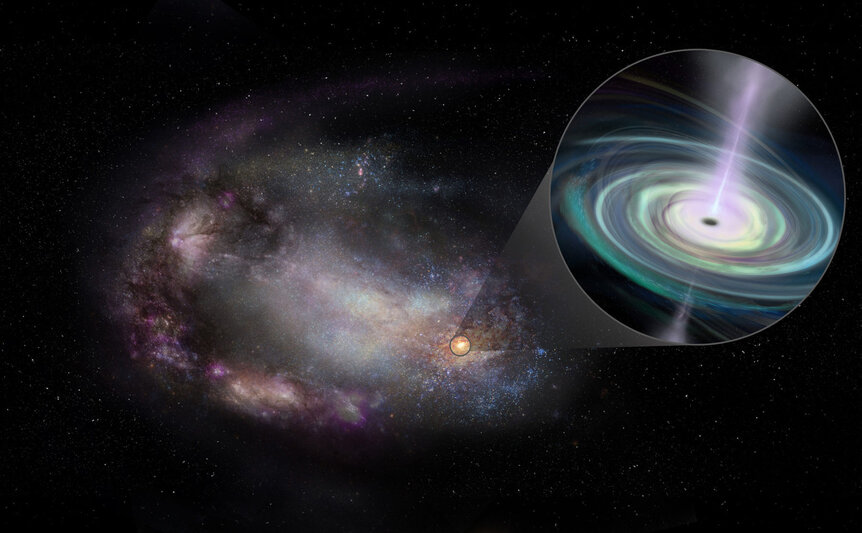

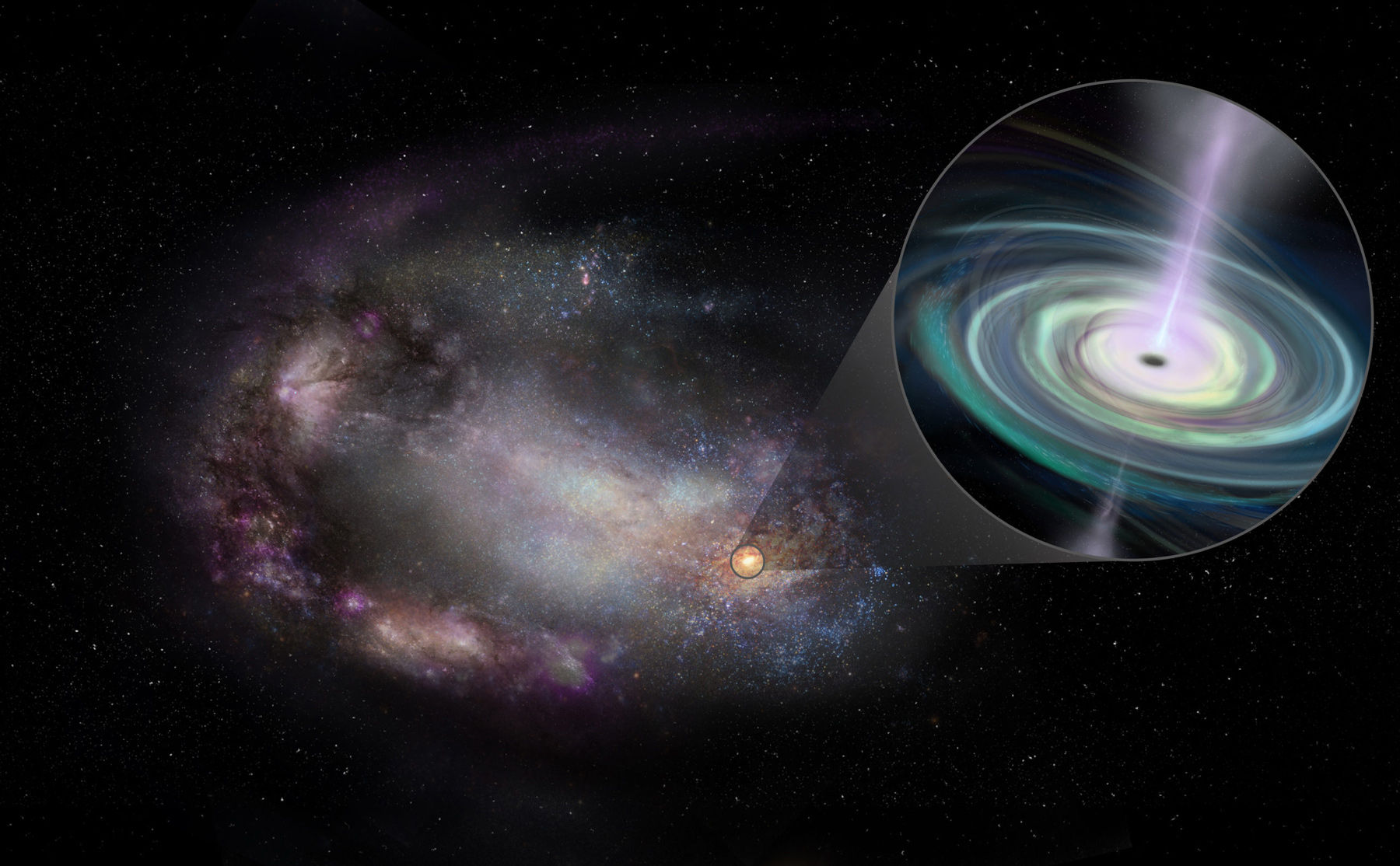

And this is where they got a surprise: When they compared the location of the supermassive black holes in the radio data to visible light images of the galaxies, in half their sample the black holes were not in the galactic centers! They were offset, clearly not sitting in the exact middle of the galaxy.

How could this be? The most likely explanation is that these galaxies have suffered massive collisions with other dwarf galaxies in the past. Galaxies do collide, and when that happens there are all sorts of gravitational effects that occur. Dwarf galaxies don't have as much gravity as bigger galaxies, making it easier for the central black hole to wander away — think of it like a shallow gravitational dip in the center instead of a sharp one. If an asymmetric collision occurs and the black hole gets a kick, it's likely to move away from the center and not as likely to fall back.

Simulations have shown that about half of all dwarf galaxies with supermassive black holes in them will have that offset, with the black hole sometimes located far from the center. And that's just what these observations found!

The sample is small (13 isn't very many), but it's pretty interesting that the numbers align so well. The authors note that there are probably a lot more dwarf galaxies like these out there; many won't emit radio waves so they weren't found in these surveys. Hopefully more of them can be detected, so that the statistics here can be improved.

These results are important for a number of reasons. As I said, these are the most common kinds of galaxies, so understanding them better is important. Also, most big galaxies today started off as much smaller ones when the Universe was young, and grew through collisions. So these nearby dwarfs are models of what many galaxies were like billions of years ago. This helps us understand how big galaxies, like our own, grow. It also helps us understand how these supermassive black holes grow, too. We still have lots of questions on how that happens, too.

It also has implications about supermassive black holes. In big galaxies, as far as we can tell, these black holes are right smack dab in the center. But that's not the case for a large fraction of dwarfs. Our galaxy ate a lot of dwarf galaxies to get to its current size… so could there be million-solar-mass black holes wandering our galaxy?

I think that's certainly possible. It's not something to worry about overmuch; the galaxy is huge beyond human scale, and a black hole with that mass would have to come very close to us to cause any problems. If they exist, the nearest one would likely be thousands of light years away. I'll note that there are cold, dark gas clouds in our galaxy with that much mass and more as well, and are likely more common. Despite that, the Earth is still here, so I'm not too concerned with getting tossed around or sucked down by a rogue semi-supermassive black hole from a previously eaten dwarf galaxy any time soon. Or ever.

So this is exciting! A whole new type of object has been found — active dwarf galaxies with supermassive black holes — and right away the first ones found are surprising and weird. I love that. It shows us (again) that the Universe is a strange place, and it also shows us that there are still lots of pieces of it we still haven't found yet.

We just have to keep on looking, keep on exploring, and keep on trying to understand this vast cosmos and delightful of ours.