Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Earth gets a close shave from the small asteroid 2017 BH30

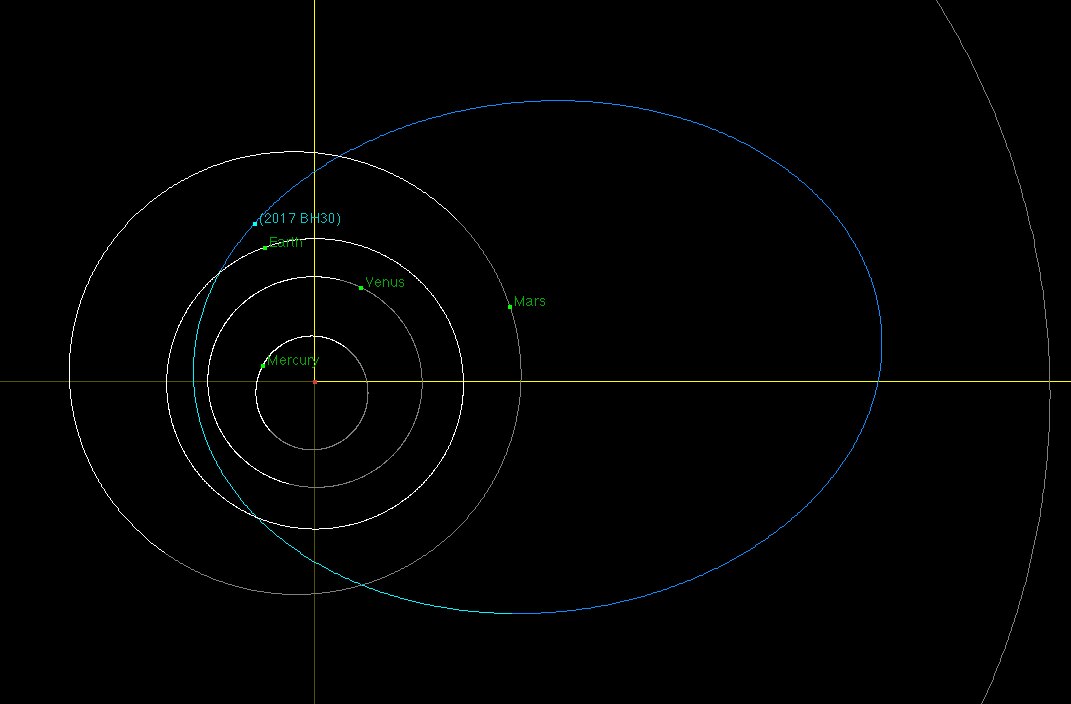

[The orbit of asteroid 2017 BH30 takes it inside Earth's orit and nearly out as far as Jupiter (large circle to the right). This shows its position on January 10, 2017, a couple of weeks before closest approach to Earth. Credit: NASA / JPL / Ron Baalke]

Last week, Earth got a very close shave by a small asteroid. I know, these kinds of things can scare folks, but I’m here to give you various levels of good news about this.

Good news: It did miss us.

Great news: We’re doing a lot better at finding rocks like this.

Bad news: We don’t really have a plan in place if one of these rocks gets too close.

So, it’s a mixed bag.

Let’s break this down: The asteroid is called 2017 BH30. On January 30, 2017, at 04:50 UTC, it missed the Earth by a squeaker, passing just 46,000 kilometers (28,000 miles) above our planet’s surface. It was discovered just one day earlier by the Catalina Sky Survey, a project that looks for near-Earth Asteroids by taking images of a large area of the sky every clear night.

The reason this asteroid was only discovered the day before it passed us is because it’s tiny, only about seven meters (roughly 22 feet) across. A typical fast food restaurant is bigger than that. That means this asteroid is faint. The faintest star you can see with your naked eye is still over 150,000 times brighter than the asteroid was when it was discovered!

I heard about it pretty quickly from my colleague Ron Baalke at NASA’s JPL, who frequently posts alerts on Twitter about passing asteroids. I looked it up on JPL’s Near Earth Object orbit simulator page and saw it was just a couple of hours from passing, and also that it would rapidly brighten enough to be spotted in smaller telescopes. I tweeted about it, asking if anyone would observe it, and got an immediate response that it had already been spotted by amateur astronomer Peter Lake. He made a short video of his observations:

The asteroid zipped past us so quickly that it appears as a long streak in one frame of his observations.

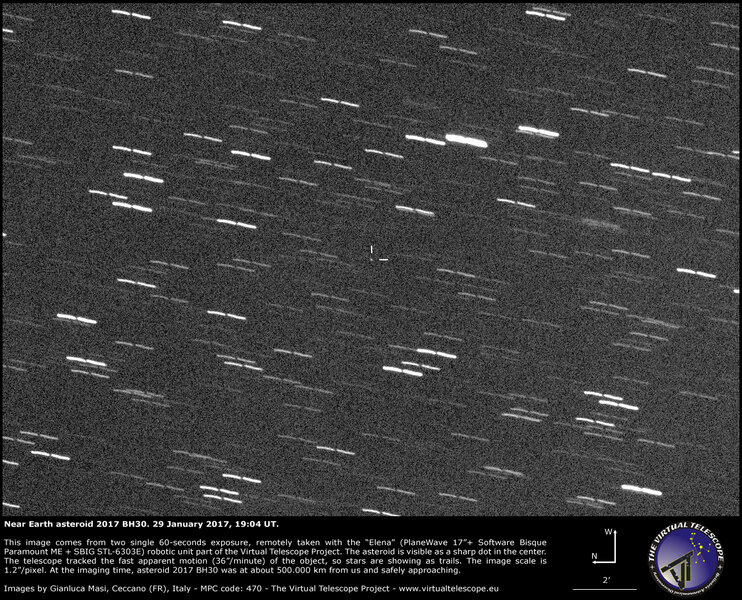

The Virtual Telescope Project also got a fine shot of it. In that case, Gianluca Masi set his telescope to track the asteroid, so it appears as a dot while the stars are streaked:

So, how close was this pass? Well, the Earth is about 13,000 km across, so it missed us by less than four Earth diameters. That’s pretty close… but still a miss.

If it had hit, it would’ve at least been a helluva light show, burning up and breaking apart as it plunged through our atmosphere at 55,000 kilometers per hour. The huge pressure generated as objects ram through the air tend to disintegrate asteroids like this rapidly, and they convert all their huge energy of motion into heat and light. That’s what we technically call an explosion. BH30 would’ve made a decent boom, equivalent to roughly 25,000 tons of TNT exploding. That’s a lot, but it would’ve happened between 50 and 90 kilometers above the Earth’s surface, far too high and weak an explosion to do any direct damage. It’s possible the shock wave from the explosion would have been audible, but I’m not sure it would’ve been strong enough to do much, if any, damage.

I base this on the Chelyabinsk event, when a 19-meter asteroid exploded over Russia in February of 2013. That was 20 times more massive than BH30, and it exploded like a half million tons of TNT. The shock wave shattered windows across the city of Chelyabinsk, hospitalizing a thousand people with wounds from flying glass. BH30 is much smaller, so the damage would have been considerably less.

...but it doesn’t matter, because it missed. And, although the orbit of BH30 brings it close to us every few years,, it’s not predicted to have another pass as close as this one for quite some time; decades at least, most likely.

But there are lots more rocks out there where this one came from. You may not know this, but the Earth is hit by about 100 tons of asteroidal and cometary debris every day. These are generally smaller than pebbles, and burn up as meteors (or, if you prefer, the less prosaic but more poetic “shooting stars”). Bigger stuff is rarer - something the size of Chelyabinsk hits us on average every 25 years or so. If that sounds like a lot, remember that ¾ of the Earth is ocean, and even the land is sparsely populated, so, until recently most of these impacts went unnoticed.

Another way to think about it: Rocks pass us all the time -- heck, look at how many passed us last month and will in the next month -- but Earth is small and space is big. That’s why we call it “space.” The vast, vast majority of these rocks miss us.

So, it goes to show you that asteroid impacts may be scary, but they’re relatively rare. The problem comes when something bigger than BH30 and Chelyabinsk -- say, 100 meters across or more -- comes in, and we don’t see it.

Which brings me back to the “good news” bit: We’re pretty good at spotting these, and getting better at discovering potentially hazardous rocks farther out, giving us more time should we need to do something. We have more observatories coming online soon, too, like the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, which should start searching the skies in the early 2020s.

And if we do “need to do something”? Well, that’s a topic for another article -- and I’ve written it -- but, to be honest, right now we don’t have any plans in the works for a mission to deflect an incoming rock should it be headed our way. I’m hoping that will happen, though given our current political situation, I have no clue what capriciousness will affect NASA. Other space agencies have made noises about this in the past, but I haven’t heard anything concrete.

While the gears of progress grind slowly, the odds of any impact are pretty low for the next few years, so we most likely have some breathing room. My hope is that more governmental space agencies will take this seriously and fund some test missions. The cost of launching them may very well be about to come down, so the price tag is getting more affordable. It’s long past time we looked into this.