Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Forget bandages: This first-ever Egyptian mud-wrapped mummy dates back over 3,200 years

In a discovery or extreme rarity and historical importance, archaeologists have identified a mud-wrapped Egyptian mummy dating back to approximately 1207 B.C., representing the initial instance of this type of hard-encased preservation practice.

According to a new research paper published last week in the online journal PLOS One, its unusual "mud carapace" indicates an ancient a mortuary treatment never documented in the entire Egyptian archaeological record.

While theories abound as to the reasons this method was used, one possibility is that the mud covering was meant to be a budget attempt at replicating the resin-based procedure of embalmment employed by the ultra rich, who were often mummified with imported resin from the late New Kingdom to the 21st Dynasty, roughly the period from 1294 B.C. to 945 B.C.

"Mud is a more affordable material," explained the project's lead researcher Karin Sowada, of the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

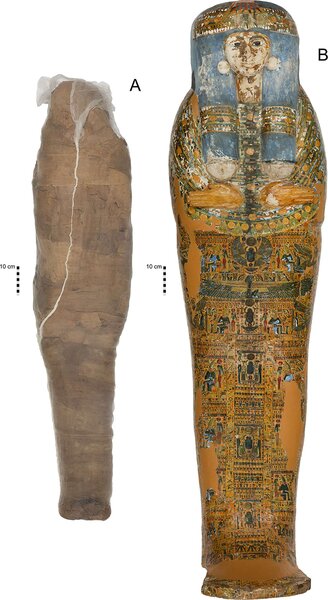

Besides the crunchy mud shell protecting the corpse, this particular mummy of a woman who died between the ages of 26 and 35 appeared to have been damaged after its demise and was found lying in an incorrect coffin intended for a female who had perished much more recently.

According to the study, this particular archaeological specimen and its accompanying coffin were obtained in the mid-1800s from Sir Charles Nicholson, an English-Australian politician and antiquities collector who took it with him to Australia. Nicholson generously donated the relics to the University of Sydney in 1860, where they are now housed at its Chau Chak Wing Museum.

However, it seems that the adventurous Sir Nicholson was duped into buying a mismatched set as the mummy dates back further than the coffin, something that occurred with great frequency as Egyptian treasures were being rounded up an sold to private individuals, academic institutions, and museums in the 19th century.

"Local dealers likely placed an unrelated mummified body in the coffin to sell a more complete 'set,' a well-known practice in the local antiquities trade," Sowada and her colleagues wrote. "The coffin is inscribed with a woman's name — Meruah or Meru(t)ah — and dates to about 1000 B.C., according to iconography decorating it, meaning the coffin is about 200 years younger than the mummy in it."

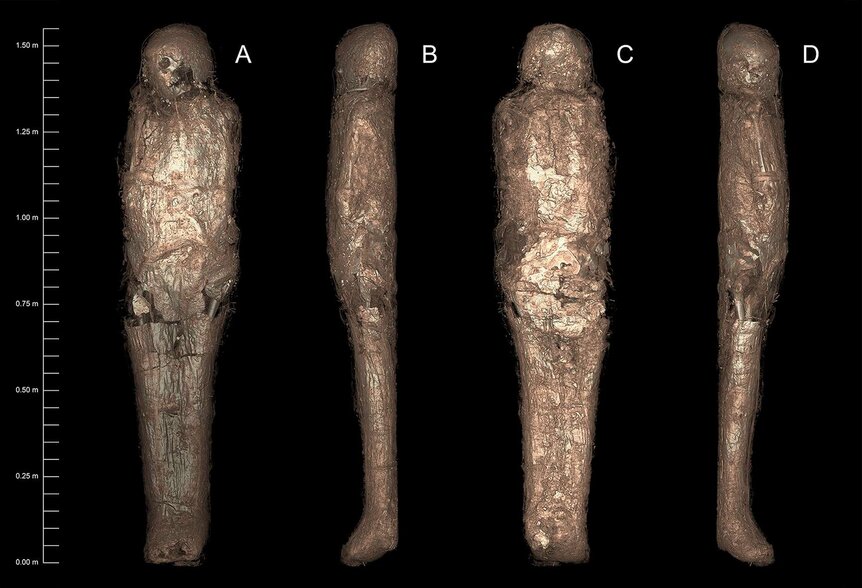

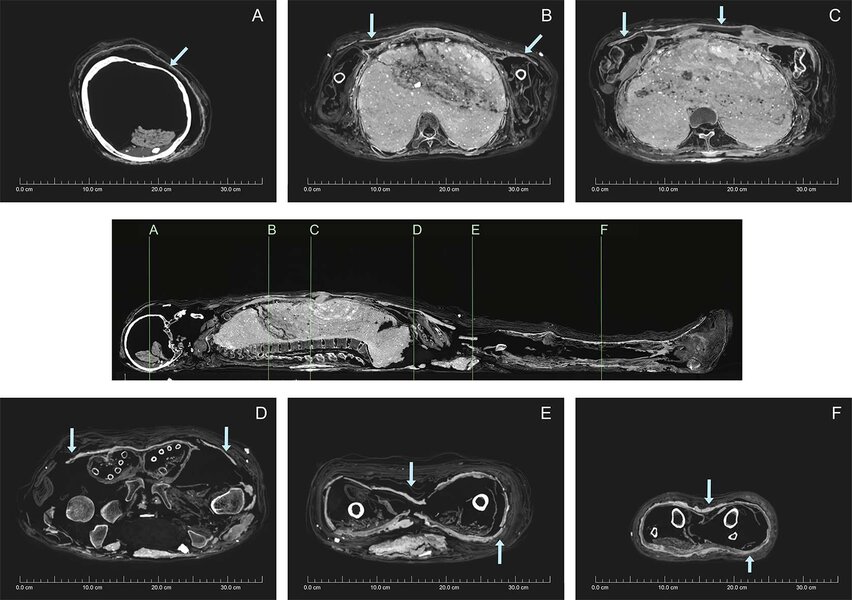

Back in 1999 during a computed tomography (CT) scan of the mummy, scientists saw some interesting images that led them to carefully extract samples of the original wrappings and saw that they were layered with a sandy mud mixture. Researchers re-scanned the specimen in 2017 and identified more intriguing details about the carapace following a chemical analysis of the crumbling bandages and ancient mud flakes.

Sowada and her crew have speculated that after dying, this person was mummified and wrapped in the normal linen tradition of the times. Damaged to her left knee and lower leg was probably caused by grave robbers shortly after her death. Indications of repair means that someone tended to the body by rewrapping, packing and padding it with textiles, and finally covered the entire corpse with a mud mixture.

"Whoever repaired the mummy made a complicated earthy sandwich, placing a batter of mud, sand and straw between layers of linen wrappings. The bottom of the mud mixture had a base coat of a white calcite-based pigment, while its top was coated with ochre, a red mineral pigment," Sowada said. "The mud was apparently applied in sheets while still damp and pliable. The body was wrapped with linen wrappings, the carapace applied, and then further wrappings placed over it."

More injury was inflicted upon the mummy towards the modern era, this time to the right side of the neck and head, which necessitated the insertion of steel pins to the affected regions.

"This is a genuinely new discovery in Egyptian mummification," Sowada added. "This study assists in constructing a bigger — and a more nuanced — picture of how the ancient Egyptians treated and prepared their dead."