Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Elon Musk Wants to Put a Million People on Mars

It’s no secret that Elon Musk wants to go to Mars. This week, he showed how he—and a lot more people—just might do it.

At the International Astronautical Congress in Mexico on Tuesday—and after teasing it for many months—he finally revealed his vision for the future of SpaceX, and possibly humanity.* It involves a big rocket, a big spaceship, a big fleet, and big money.

Perhaps you sense a theme here. Bigness.

He calls it the Interplanetary Transport System, or ITS, and he’s not thinking small: He claims this plan can lead to a city on Mars of 1 million people or more, and it could be well on its way in less than a century. It’ll take thousands upon thousands of individual rocket flights.

What he and his company are planning is not in any way easy, and as he himself pointed out with characteristic understatement in a press conference after the announcement, “A lot of things have to go right.”

Yes indeed. So what exactly has to go right to put humanity on the Red Planet?

The Hardware

The plan is to use an enormous rocket, comfortably larger than the Saturn V that sent humans to the Moon, topped with a spaceship that can hold as many as 100 people. It will go to orbit, be refueled using multiple launches, blast its way to Mars, enter the atmosphere using aerodynamic braking to slow, then eventually land on its tail.

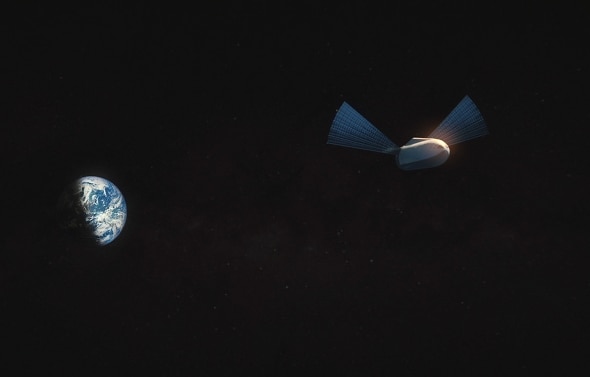

SpaceX put together a pretty dramatic animation of the basic flight:

Watching that I felt like I was seeing an updated version of movies I used to watch as a kid. But having thought it over, I have to say that what Musk is planning is doable. Yes, seriously. The engineering challenge is formidable, but technically possible.

There are four critical engineering steps needed to make all this a reality: The rocket must be fully reusable, the spaceship (the section that will actually go to Mars with people and supplies) must be refilled with fuel and oxygen on orbit, the right propellant must be used, and there must be a means of making that propellant on Mars itself.

None of these is easy. Not by a long shot. But they are possible.

First, the rocket. The as-yet unnamed booster is beefy. It’ll be 122 meters tall and about 12 meters wide (the Saturn V was 111 x 10 meters in size). That’s big. But it’s the thrust that shocked me: It’s planned to have a staggering 13,000 tons (29 million pounds) of thrust. The Saturn V—still to this day the most powerful rocket ever launched—had a thrust of 3,500 tons (7.5 million pounds). The SpaceX booster will have a thrust 3.5 times as much as that.

Thrust is one way to characterize how much stuff you can throw into space. This booster will be able to throw a lot. It should lift about 500 tons into Earth orbit, which is a huge payload. The heaviest payload the Space Shuttle took to orbit, the Chandra Observatory, had a mass of about five tons.*

That huge thrust is good, because the Mars spaceship will be huge, too. Measuring about 50 meters long and 19 meters wide, it’ll be so heavy that even the enormous booster won’t be able to put it into orbit by itself. After the booster drops away, the spaceship (again, also as-yet unnamed) will use its own engines to get the rest of the way to orbit, using most of its fuel doing so.

That means the spaceship will have to be refueled. Or, as Musk put it, “refilled”; it’ll need fuel and oxygen used to burn the fuel. That’ll need more rocket launches, which in turn means the booster must be reusable. Like the Falcon 9 first stage, which has now been successfully relanded a half-dozen times; after boosting the spaceship as fast and high as it can, the giant rocket will turn around, slow, descend, and then land itself back at Cape Canaveral in Florida. Musk notes that they’re getting pretty good at this with the Falcon 9, and each landing is more accurate.

The ITS booster could be back on the pad after as little as 20 minutes. It’ll be inspected, and if it’s good to go a tanker full of fuel and oxidizer will be mated to it. The tanker is basically the same design as the spaceship itself (redundant designs save a lot of money and time to develop). It’ll launch into orbit, meet up with the spaceship, mate, and transfer the fuel. This may have to be done several times to give the ship enough fuel to get to Mars.

Once that’s all done, the spaceship leaves Earth orbit, accelerates to interplanetary speed, coasts for a few months, then arrives at Mars. Like the Space Shuttle Orbiters, it will slam into the Mars atmosphere and use drag to slow it down—parachutes for a ship this size are impractical—and then use its engines to land on its tail, just like in those old movies.

But we’re not quite done. To make the spaceship fully reusable (to save on cost per flight), it will need to tank back up and return to Earth (perhaps with people and supplies if needed). To do that, it’ll need to make its own fuel.

This part of the plan is probably the hardest, technologically speaking. The rocket and spaceship will use a new engine SpaceX calls Raptor (the first test model has already been built and underwent a test firing just the other day). It will be more powerful than the Merlins currently used by the Falcon 9, and will use extremely cold liquid methane for fuel. This has some advantages over current fuels; while tricky to design the engine, it does allow for more thrust and a bigger rocket, but most importantly it can be made on Mars! There’s lots of water there in the form of ice, and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Using various methods, these can be processed into methane to make more fuel.

So there you go. Easy peasy, right?

Welllll …

Some Issues

There are some issues with this. For one, we’re not really sure how to make the fuel on Mars, or how much it will cost. The chemistry of it is understood, but in practical terms the ice has to be mined, purified, and processed, and all that has to be done in quantity. That’ll take a lot of machinery, and a whole lot of robust engineering to make sure it works right. Repairs will be difficult until the base becomes sufficient.

Nothing this large has ever been attempted before, either. Despite recent setbacks, SpaceX has been doing pretty well with the Falcon 9, and has learned a lot about bringing boosters back, making reusable vehicles, and the like.

But there’s a helluva long way to go to get to the point where this huge rocket can be built. They need to learn how to do autonomous docking in space (that’ll be tested next year with the Dragon capsule berthing to the space station). They need to relaunch a used booster, and not just once, but multiple times. And of course, SpaceX still hasn’t sent any humans to space.

I’m not saying any of those are show stoppers. Just that this is a long, long road, and SpaceX is just now pulling onto it.

Still, I have some bigger concerns. For example, a trip to Mars using the ITS will take roughly 80 to 140 days (Mars has an elliptical orbit, so sometimes the dance of the planets brings it closer to Earth than other times, so this is an average). This raises the danger of radiation. Normally this isn’t all that big a deal; in interplanetary space, levels are low. But if there’s a solar storm like a flare, this can send deadly waves of subatomic particles racing into space. If such an event occurs, astronauts will have to be protected.

Musk was remarkably cavalier about this, saying it’s not that big a deal. I disagree; it’s something engineers will have to plan for, especially given the sheer number of flights planned. Over 10,000 trips, the odds of a ship getting hit are very high indeed. Water is an excellent shield, and the ships will need plenty of it, so designing the transport to use it that way would be beneficial.

There’s also the issue of recycling air and water, and how that many people will get along for the months of hopefully uneventful travel through interplanetary space.

Also, it’s not clear to me what will happen when the first ships get to Mars. They’ll need protection from dust storms, from radiation, and also just a place to live. I know that this isn’t the kind of thing this presentation was meant to cover in detail, but some mention would’ve been nice to hear. If Musk really wants a million people to live on Mars, those first few will need shelter.

Mars Needs Money

Also, how this enormous undertaking will be financed is a bit hazy. Musk said that SpaceX is funding this right now, spending a few tens of millions of dollars per year on research. The Raptor engines have been funded privately, though recently the Air Force kicked in some dough). Eventually, once the final designs of the Falcon 9 are implemented, the company will spend more resources on it. They still need to get the Falcon Heavy off the ground as well, which hopefully will happen next year.

The costs of developing and launching the ITS are formidable: It’ll cost more than $500 million just to manufacture a single rocket, spaceship, and tanker. Even if it’s reused many times, this is still a lot of cash, especially when you remember that Musk wants to launch thousands of these things.

SpaceX obviously can’t do it alone, and Musk said he hopes NASA and private companies can pitch in. There is some reason to do so; the engineering will be very useful and easy to spin off, and NASA is very interested in data SpaceX generates. The company is making money on contracts now, and heavy lift vehicles like the Falcon Heavy and the ITS booster could turn a profit for the company.

I strongly suspect that the ITS will cost far less than NASA’s Space Launch System, too, which will cost more than $1 billion per flight (and is not reusable). SLS hasn’t been built or launched yet, so we’ll have to see how it will compare to ITS. Musk hopes to complete the initial development of the first ITS booster in 2020, and send people to Mars in about 10 years or so.

That’s possible. SpaceX has plans to send an uncrewed Dragon capsule to Mars in 2018, though realistically, given inevitable delays, they may have to wait until the 2020 apparition to launch (the same year NASA will send the Mars 2020 rover there, too). Musk wants to send people to Mars by 2024 as well.

But we’re talking a lot of money, at least a $10 billion investment before money starts to be made back. Musk talked about the cost per person to go to Mars as a way to judge the efficacy of this, and more than once talked about people “buying a ticket” for $100,000 to $200,000. It’s possible he might sell some, given that it could be a round trip, but I’m not sure people will pony up that kind of money to go live on Mars until it’s a viable habitat.

So, Will This Work or Not?

So what’s the bottom line? Is this possible?

The answer is yes, it’s certainly possible. But is it doable?

That one I’m not sure about. I think it very well may be, but again fortune will have to smile down a lot on Musk and SpaceX.

Still. Musk has pulled a rabbit out of his space helmet more than once in the past. SpaceX was nearly bankrupt when it finally got a Falcon 1 rocket off the ground, and showed it could go to space. The loss of a vehicle in 2015 slowed but did not stop them, and neither will the more recent Falcon 9 loss. SpaceX has built up quite a bit of momentum, and the Falcon 9 is still operating at a more than 90 percent success rate. And their ability to develop their own engines and bring a booster back from space is very, very impressive (Blue Origin is doing this as well).

While I can’t say for 100 percent sure we’ll be seeing people going to Mars on a rocket with SpaceX’s logo on the side using the ITS … I wouldn’t bet against Musk.

Why?

And finally, there’s one more question: Why do this? What motivates Musk?

As he said at the announcement:

It would be an incredible adventure. I think it would be the most inspiring thing that I can possibly imagine. And life needs to be more than just solving problems every day. You need to wake up and be excited about the future. And be inspired, and want to live.

I agree. And while some people have quoted him as saying he “wants to die on Mars,” when I talked to him in 2015 about this he waved off this as a bit of headline link bait. Then why go, I asked him.

“Humans need to be a multiplanet species,” he replied.

I agree with that as well. It’ll happen, inevitably, if we choose to make it happen. Musk has made his choice. I hope it pays off. It very well might.

*Correction, Sept. 29, 2016: This post originally misidentified the International Astronautical Congress as the International Aeronautical Conference.

*Update, Sept. 30, 2016: The mass of the observatory was about five tons, but it also had a rocket booster attached that brought the total payload mass to more than 20 tons. Not incidentally, the shuttle Orbiters had masses of roughly 80 tons as well.