Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Exoplanet news Part 4: More wretched hives of scum and villany

[I'm trying to catch up with all the news that's been released this week while I was off lecturing in Texas. This is Part 2 of a few articles just about exoplanets. Here's Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.]

Astronomers have found more Tatooines! Cool.

Astronomers have found more Tatooines! Cool.

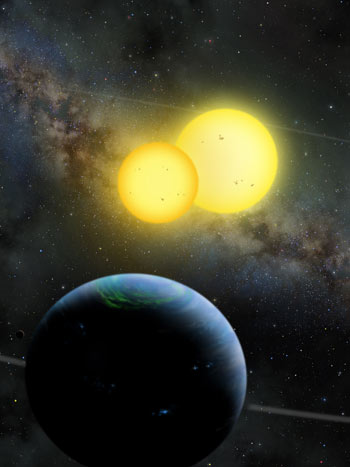

In September, astronomers announced the discovery of a planet (Kepler-16b) that orbited not one but two stars. The stars orbit each other (in what's called a binary system) and the planet circles both. This was the first such planet found doing this (out of hundreds of planets orbiting single stars discovered), which opened up the question: how rare is this kind of system? Is Kepler-16b one of a kind?

The answer appears to be no: two more such systems have just been announced! Dubbed Kepler-34b and Kepler-35b, both are gas giants, similar in size to Saturn.

The planet Kepler-34b orbits two Sun-like stars once every 289 days. The two stars (Kepler-34A and Kepler-34B; note the capital letter denoting a star versus the lower case letter denoting a planet -- which technically should be called Kepler-34(AB)b, but at some point I have to draw the line and simplify) orbit each other every 28 days. The planet Kepler35-b orbits a pair of somewhat lower-mass stars every 131 days (the stars orbit each other every 21 days).

Note that in both cases, the planets orbit their stars at distances much larger than the distances between the two stars themselves. That's not surprising to me. From far away, a circumbinary planet (literally, "around two stars") feels the combined gravity of the two stars more than either individual star, much like distant headlights on the highway look like a single light. When you're close, the two lights resolve themselves. Same thing with a planet; if it orbits much closer in the gravity field is a bit more distorted by the individual stars. Too close, and the orbit becomes unstable and the planet can be ejected from the system entirely! But it looks like both Kepler-34b and 35b have nice, stable orbits.

Binary stars are very common in the Milky Way: roughly half of all stars are binary, and now we know that at least three such systems have circumbinary planets. And we've only just started looking! Mind you, these planets were found using the transit method, so the orbits have to align just right from our viewpoint or else we don't see them transit. For every one transiting system we find there are many more that exist but don't transit, so we don't see them. But they're out there.

I suspect that the fraction of binary stars with planets is probably lower than for single stars, since planets forming (or moving) closer in to the binary center will get ejected. But still, even with a lower fraction we're still talking about a pool of hundreds of billions of stars, so it's likely that there are millions of circumbinary planets out there: millions of Tatooines!

And hmmmm. Kepler 34 and 35 are 4900 and 5400 light years away, respectively, making them among the more far-flung planetary systems seen. You might say that if there's a bright center to the Universe, they're the planets that it's farthest from.

I've always dreamed of standing on a hill and watching twin suns set in the west. Sadly, the wind won't blow through my hair like it did Luke Skywalker's, but that would be a small price to pay. What a view that would be!

[UPDATE: Wait a sec! Right after posting, I realized: the two planets are both gas giants, but far enough from their stars that big, terrestrial moons might be possible. So imagine that: a binary sunset with a gigantic planet looming in the sky as well! That would be incredible.]

Image credit: Lynette Cook and SDSU