Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Creepy extinct fish with fingers unearths the bizarre truth of how hands evolved

No, not those fish fingers. Defrosting and a microwave weren’t required here.

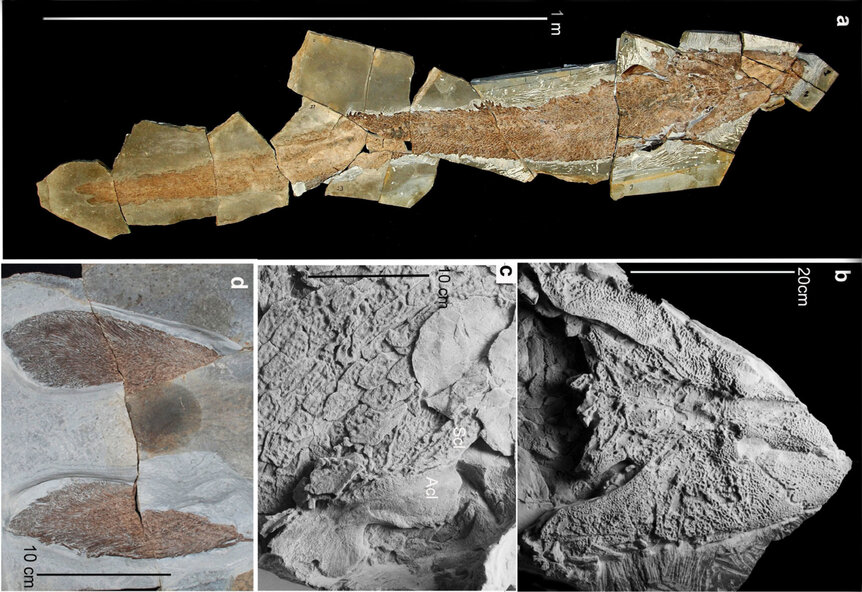

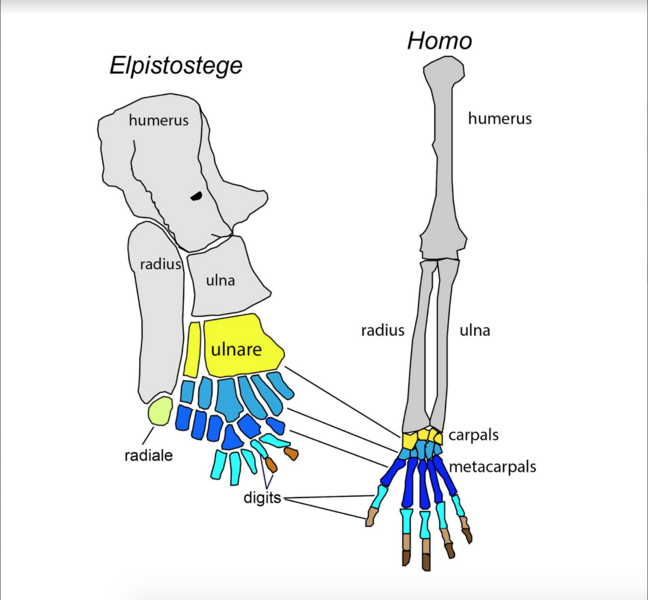

Humans may not be directly related to fish (except maybe Abe Sapien or that creature from The Shape of Water), but the fossil of an extinct fish known as Elpisostege watsoni was a breakthrough for a research team from Flinders University in Australia and Universite de Quebec a Rimouski in Canada. This literal fish out of water had fingers, as in actual finger bones, in its pectoral fins. Its 380-million-year-old skeleton revealed how vertebrate fingers evolved from fins — and how prehistoric fish morphed into tetrapods.

The find “reveals extraordinary new information about the evolution of the vertebrate hand," said John Long, Strategic Professor in Paleontology at Flingers University, who recently published a study in Nature. “This is the first time that we have unequivocally discovered fingers locked in a fin with fin-rays in any known fish. The articulating digits in the fin are like the finger bones found in the hands of most animals."

Elpisostegalians were amphibious predators that merged features of fish and tetrapods. They were the closest known evolutionary ancestors of tetrapods, but are thought to have appeared more fishlike (closer to how you would probably imagine a fish-crocodile hybrid) since they still had the scales and gills. Their large skulls with eyes on top were parts of their morphology closer to tetrapods, and unlike fish, they had insignificant dorsal and anal fins or none at all, relying instead on their pectoral fins to carry them around in shallow water or all the way to shore. Finger-like bones made it easier for them to spread their weight through those fins.

No other fossils have revealed the complete anatomy of an elpisostegalian’s extraordinary pectoral fins until now. Out of four elpistostegalian species, E. watsoni is the only one whose body shape and proportions can now be fully fleshed out.

Tetrapods are thought to have emerged in the form of elpisostegalians during the Devonian period. Earlier fossilized impressions of bones that suggested the beginnings of a transformation do exist, but these not-quite-fish, or tetrapodomorphs, which probably “walked” something like this, marked the dawn of the transformation into tetrapods. What may have deceptively appeared to be a fin could have been mistaken for one, since it still shows fin rays characteristic of fish. These fins were actually hiding skeletal digits that Long and his team determined to be the closest skeletal structure to tetrapod hands ever found.

"This finding pushes back the origin of digits in vertebrates to the fish level, and tells us that the patterning for the vertebrate hand was first developed deep in evolution, just before fishes left the water," Long said.

So where did fish end and tetrapods begin? The Devonian phenomenon of fish fingers was undoubtedly one of the most significant events in vertebrate evolution. Later incarnations of tetrapodomorphs would eventually ditch the gills for lungs and further adapt to terrestrial life by developing stronger muscular structures in fins that were turning into legs. Dorsal and anal fins that are necessary for stability and swimming in water also disappeared. Functions of major organs began to change, and sensory abilities to detect movement of predators and prey in water gradually faded, though E. watsoni was probably not in much danger of being eaten since it had fangs for days.

“Elpistostege further blurs the line between fish and tetrapods in showing a greater number of tetrapod novelties than are present in any other ‘fish’,” Watson and his team concluded in the study.

Just hope that monster sharks won’t start taking sunset walks on the beach anytime soon.

(via Flinders University/Nature)