Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Helium-Filled Planets

Well, here’s something that never would have occurred to me: Lots of exoplanets (alien worlds orbiting other stars) may have helium-rich atmospheres. We don’t have any planets like this in our solar system, so this is something of a surprise.

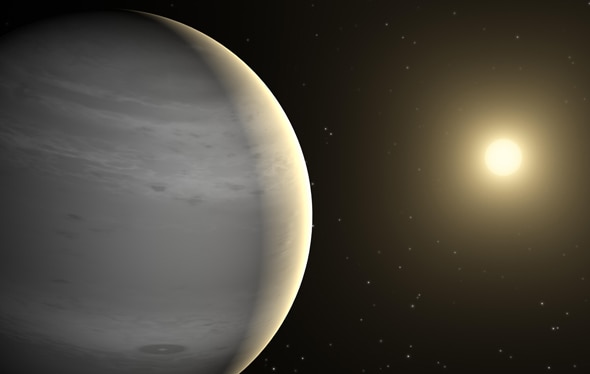

The planets in question are called “warm Neptunes,” because they have about the mass of Neptune (17 or so times that of the Earth) and orbit their parent star very closely, closer than Mercury orbits the Sun. The Kepler Observatory, designed to hunt for exoplanets, has found hundreds of candidates that match this profile.

Our technology is getting so good that we can actually get low-resolution spectra of some of these planets, which allows astronomers to get an idea of the compositions of their atmospheres.

One such warm Neptune, GJ 436b, was a surprise: It has almost no methane in its atmosphere. In fact, according to physical models of the atmosphere you’d expect the planet to have, it only had 0.00001 as much methane as expected!

It’s possible it has a thick haze layer over its atmosphere, blocking the signal from methane. It’s also possible it just doesn’t have much methane. Assuming the latter, why?

A team of astronomers has come up with an idea: The assumption in the models is that the atmospheres of these planets are mostly hydrogen (which is true for the giant planets in our solar system). Methane is made up of carbon and hydrogen, and if the hydrogen is gone, you can’t have methane. Not only that, but if there’s no hydrogen, carbon would be more likely to pair up with oxygen, and in fact carbon monoxide was seen in GJ 436b’s atmosphere (making it less likely that it’s just haze blocking our view).

So where did the hydrogen go?

This part’s clever. The planets orbit so close to their stars that the hydrogen evaporated away due to the heat. Hydrogen is the lightest element, so when you heat up a planet like that the hydrogen will be the first to be lost. We do see hydrogen in hot Jupiters, more massive planets orbiting closely to the stars, but these planets have more gravity and can hold on to the hydrogen better. Something with the mass of Neptune (only 5 percent the mass of Jupiter) has less gravity and can’t hold on to the lighter element.

The next most abundant element in giant planet atmosphere is helium (four times heavier, per atom, than hydrogen). That means that these warm Neptunes would have proportionately a lot more helium than planets in our solar system, and in fact may have air that’s mostly helium!

They would look decidedly odd to our eyes. Instead of the deep rich colors of our gassy planets, these helium planets would be somewhat colorless, gray or white. How about that?

I love this. This isn’t an obvious result at all (at least not from our experience, looking at planets in our own solar system), and it shows that the Universe is more clever than we are. It also shows that basing our assumptions of other planets on what we see in our own neighborhood is naive, and ultimately limiting. We need to be open to the rich diversity of Nature, to appreciate that given even slightly different conditions to start with, circumstances can wind up very differently.

And that’s what makes the Universe so much fun to study.