Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Here’s What a Comet Looks Like When You’re Close Enough to Touch It

On Aug. 6, 2014—and for the first time in human history—a spacecraft caught up to a comet with the intent of staying there. We’ve flown past a half dozen or so cometary bodies over the years, but never before has a probe made a rendezvous packed for the long run; the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft will orbit the comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko for more than a year, examining its surface, interior structure, mineral composition, and the gases it ejects as it orbits the Sun.

From Rosetta’s current distance of 100 kilometers astonishing detail can be seen … but it’ll get even better in the coming weeks as it slowly drops down, lowering its orbit, culminating in deploying the lander named Philae to the surface of this icy comet.

In the meantime there are pictures galore, science to be learned, and wonder to be experienced. And not just with the comet, but also with a few other cosmic objects Rosetta passed along the way on its 10-year voyage to its historic rendezvous. Here are 10 of my favorite pictures returned from the distant spacecraft … so far.

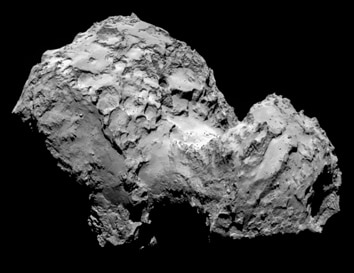

Comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko

Behold, the comet! Rosetta took this shot on Aug. 3, 2014, just days before it arrived. From a few hundred kilometers away a lot of detail is visible, including the weird overall “rubber ducky” shape, the oddly sculpted jagged spires, lots of circular features that may or may not be impact craters (we may find out over time as Rosetta gets more observations of these features), and even boulders lying on the surface in the weak gravity of the 4-kilometer-long chunk of dirty ice.

Bottom Up

On Aug. 6, the day of arrival, Rosetta got this observation of the bottom of the main body of the comet. The smooth area may be due to ice turning into a gas, erupting from the comet, then replating back down on the surface. You can see cracks, ridges, and more boulders, especially in the close-up shot of this same region.

NAVCAM Locks On

On the last day before Rosetta arrived at the comet, the low-resolution navigational camera took images of the target. My friend Emily Lakdawalla at the Planetary Society assembled these images into a single montage, showing the comet nucleus over two of its 12.4 hour “days.” You can see the comet getting bigger as Rosetta slowly approached, with more surface details becoming visible. The tiny dots you see on each image are from the camera itself and are not real surface features on the comet.

67/P in 3-D

One of the advantages of approaching a rotating comet is that you can take two images taken at slightly different times, which means you have slightly different angles on the target. That in turn (“turn”! Haha! I kill me.) means they can be combined to form a three-dimensional picture called an anaglyph. If you have red/green glasses (and given how many anaglyphs I post, you should) then you’ll see this image as an amazing 3-D picture that seems to come right out of the screen. It was created using images from Rosetta’s main OSIRIS camera and the NAVCAM by amateur astronomer Daniel Machacek, a frequent contributor to the Planetary Society website.

Comets Visited by Spacecraft

Rosetta is making history by being the first spacecraft to orbit a comet, but it’s not the first to visit one. In total, six comets have been the targets of probe flybys, including Comet Halley. This poster, care of my friend Emily Lakdawalla at the Planetary Society, shows their nuclei (their solid parts) to scale with each other. The obvious characteristic is that none is really round and in fact at least half are bipolar—bowling pin shaped. The comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko is, with one lobe quite a bit larger than the other. Although it’s a small sample size it’s possible many comets are shaped this way. It’s unclear why; perhaps they are the merger of two smaller comets, or material evaporated away to leave this shape, or low-speed impacts shatter the comets that then recoalesce this way. Hopefully, Rosetta’s long-term lease at 67/P will help solve this puzzle.

Moonrise

Rosetta launched in March 2004, and a year later flew past the Earth to pick up some needed energy to fling it farther out in the solar system. This was the first of three fly-bys, and as it passed over the Earth it took this dramatic shot of the crescent Moon rising over the Pacific Ocean. This shot was taken at 22:06 UTC on March 4, 2005, just three minutes before closest approach to Earth—when the spacecraft was about 2,000 km (1,200 miles) above Earth’s surface.

Close Encounter With a Red Planet

After the Earth flyby, Rosetta headed out to Mars, using the smaller planet’s gravity and orbital motion to again get a bit of energy. It came to within an astonishing 250 km of the planet’s surface, but four minutes earlier, at 1,000 km out, a camera on the Philae lander took this amazing picture showing part of the spacecraft itself with Mars in the background.

Mars

On Feb. 24, 2007, when it was about 240,000 km (130,000 miles) out, Rosetta took this incredible full-disk image of Mars with its main OSIRIS camera. It was the first three-color image taken by the camera that closely represents what the eye would see.

Lutetia

On its way out to the comet, Rosetta flew past another rock: Lutetia, a 130-km-wide asteroid. Rosetta never got closer than about 3,100 km, but that was enough to take some amazing shots, including this one, which shows craters and grooves along the asteroid’s surface.

Home

Rosetta passed Earth a total of three times, and—on Nov. 2, 2009, just five hours after closest approach on its very last pass—it took this shot, what I consider to be one of the finest images of our home planet ever taken. Rosetta was 633,000 km (390,000 miles) away when it took this picture, and the photo shows the South Pole of Earth, clouds whirling around Antarctica.

Remember, these are just the beginning. Although Rosetta has traveled for more than 10 years, it's just now reached its ultimate goal, and there is much, much more yet to see.