Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

In 774 AD, the Sun blasted Earth with the biggest storm in 10,000 years

In the year 774 AD, an enormously powerful blast of matter and energy from space slammed into Earth.

Nothing like it had been felt on this planet for 10,000 years. A mix of high-energy light and hugely accelerated subatomic particles, when this wave impacted Earth it changed our atmospheric chemistry enough to be measured centuries later.

Our pre-electronic societies went entirely unaffected by it. But were this sort of event to happen today, the results would be bad.

It was first discovered by an analysis of tree rings, of all things. Scientists found that the level of carbon-14, an isotope of carbon, was much higher in rings from that year than usual. Some years later, looking at air samples from ice cores, scientists saw that there were elevated levels of beryllium-10 and chlorine-36 as well.

The common factor in all these elements is that they are created when extremely high-energy subatomic particles hit Earth's air and ground. They slam into the nuclei of atoms and change them, creating these isotopes. The only way to get particles at energies like this is from space, where powerful magnetic fields in exploding stars, for example, can accelerate the particles to such high speeds. We call these isotopes cosmogenic, made from space.

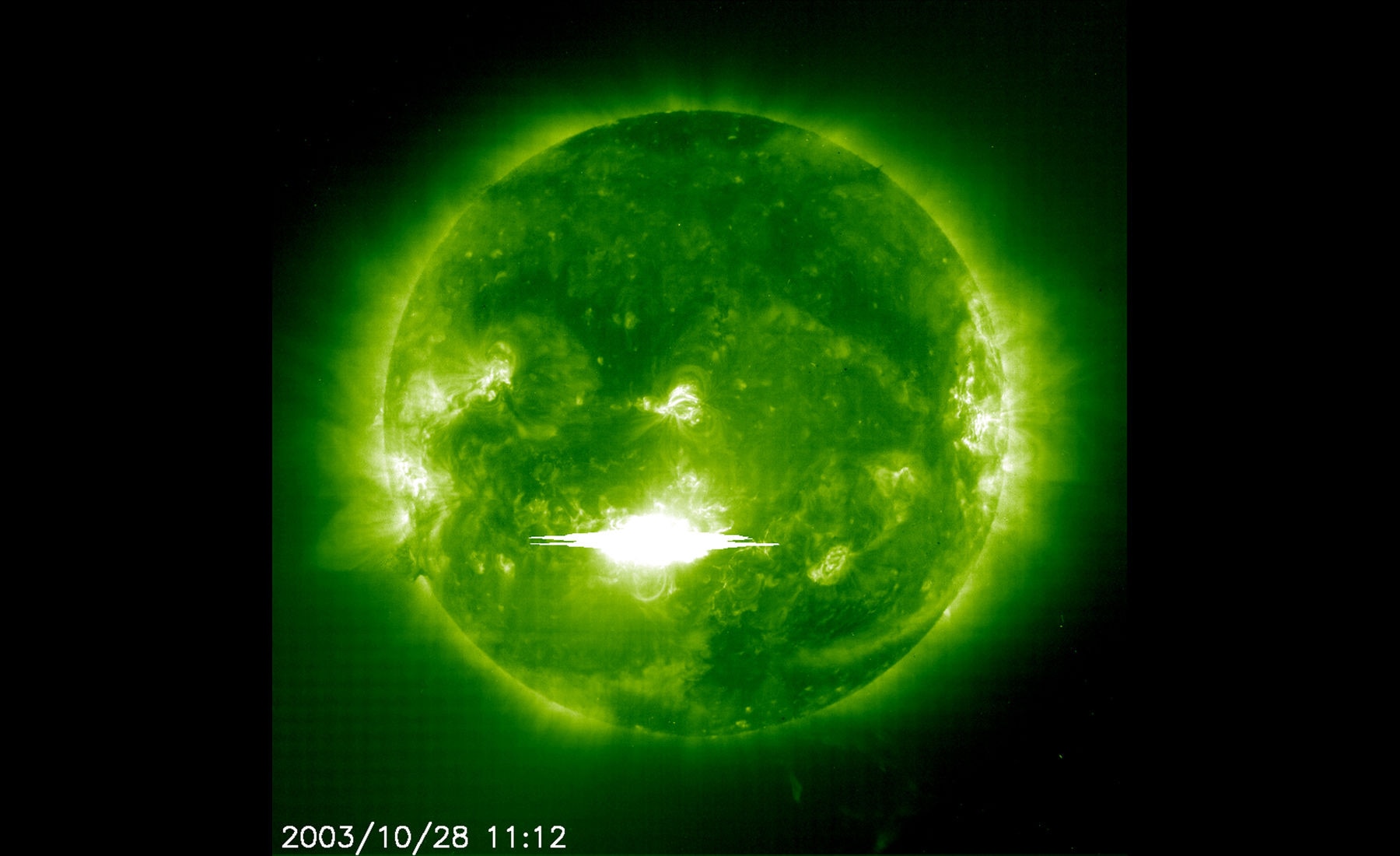

What could have created the space storm in 774 AD? The obvious candidate for such a thing is a very powerful solar flare, an explosion on the Sun created when intense magnetic field lines tangle up and short circuit, releasing huge blasts of energy and particles. But the 774 event was so powerful that at first scientists were skeptical it could be from a flare. Once any other type of astronomical phenomenon was ruled out, though, a flare was all that was left.

A team of scientists has gone through the records to look at other such events in the hopes of categorizing this flare compared to other known flares. What they found is that this event was by far more powerful than even some relatively scary modern flares.

For example, in 1989 the Sun erupted in a powerful series of flares as well as a huge coronal mass ejection (or CME), where billions of tons of hydrogen plasma is ejected at high speed. Carrying its own magnetic field, this bout of space weather slammed into the Earth's magnetic field, affecting it so profoundly that electric currents were induced under the Earth's surface. Called geomagnetically induced currents, this extra electric energy blew out transformers in Quebec and caused a power outage that lasted for hours.

In February 1956 was the most powerful solar storm in the modern era, which was easily twice as strong as the 1989 event. Our power grid wasn't as heavily used at that time, so it didn't cause the same sort of damage as the 1989 event, but was still a huge event.

Using various methods to characterize the 1956 storm, including measurements in visible light, radio waves, changes to the Earth's ionosphere (a high-altitude layer of ionized air that, when it changes rapidly, can affect magnetometers on the ground that measure magnetic field strength), and more, they found the 774 AD event was a staggering 30 to 70 times stronger. This means it was likely 100 times stronger than the one in 1989.

It's not clear how long the flare lasted; most strong ones grow and decay in a matter of hours. But the total energy released in this flare was about the same as what the entire Sun radiates in one second: 2 x 1026 Joules, or the equivalent of roughly 100 billion one-megaton bombs going off.

That's a lot of energy. Enough to power our entire planet (given our current energy use) for 300,000 years.

Yegads.

A flare like this is called a superflare, and until now it wasn't thought the Sun could produce them (other stars that are more active magnetically make them quite often). The scientists think the 774 flare may have been a special circumstance, where a powerful flare occurred near a streamer of gas called a filament, slamming it and accelerating the protons in it to such high energies.

That's actually something of a relief! I'd prefer that it's hard for the Sun to do this.

Such an event happening today would be catastrophic. It could take out numerous satellites — the particles and high-energy radiation can short out even hardened electronics — and cause widespread blackouts. Those could take a long time to fix, since the bigger transformers used by power grids cannot be mass-produced. Some scientists calculated that passengers on international airplane flights could receive a lifetime dose of radiation in a few hours from such an event.

The effects on Earth can be difficult to determine; in part it depends on the whether the flare and CME's magnetic polarity (the north-south part of the magnetic field) is able to couple with the Earth's magnetic polarity. If it does we get the blackouts and other damage. But some of the effects occur either way.

I'll note that we haven't seen as powerful an event since 774, though many have been quite strong. The Sun erupted in 2012 in a coronal mass ejection that, had it hit the Earth, would've been worse than the 1989 event. Happily it was sent off in another direction.

But it's clear the Sun can have some pretty big tantrums, and we need to take this seriously. Certainly solar astronomers do, and as the Sun ramps up into the newest magnetic cycle they're looking at our star with everything they have. We don't know how strong this cycle will be; one prediction is that it will be no big deal, but another says it very much will be.

We'll see. There's clearly a lot more we have to learn about the Sun. It's not an exaggeration to say that our modern lives depend on it.