Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Interstellar Science

Correction, Nov. 9, 2014: The basic assumptions I made about black holes in this movie were incorrect, so the conclusions I drew below were incorrect. This needs some explaining, so please read my follow-up post that hashes out my errors.

I generally enjoy writing movie reviews; they’re a fun way to gather my thoughts about a movie, analyzing its plot, the production, the writing, even the science.

It’s for that very reason I dreaded writing this one. I was really looking forward to seeing Interstellar … but I thought it was awful. A total mess. So if you’re looking for a tl;dr, there it is. I really, really didn’t like it. And I really, really wanted to.

What makes it worse is that the movie could have been truly great. The overall plot isn’t bad (if a rehash of an old science fiction idea), and some of the ideas in it were solid. The special effects were breathtaking. Outstanding. But they can’t carry a movie with leaden dialogue, obvious foreshadowing, ham-fisted philosophy, and a serious but misguided attempt to be deep. And a lot of the critical details in the plot were a mishmash of ideas that made no sense.

And the science. Oh dear. The science.

From here on out there will be spoilers, so fairly warned be thee, say I.

Plot Boiler

The plot is hard to synopsize, but here’re the bullet points: In some unspecified time in the future, likely more than 50 years hence, the world is in ecological disaster. Crops are failing, food is scarce, billions have died. Matthew McConaughey plays Cooper, an ex-pilot and engineer who is now struggling to grow corn on his farm along with his father-in-law, son, and daughter Murph. His daughter complains of a ghost in her room that’s trying to send her messages. Initially dismissive, Cooper discovers the messages are real, are encoded using gravity somehow, and include coordinates to a location somewhere within driving distance.

Cooper and Murph discover a secret NASA base at those coordinates, and Cooper is told that half a century before, a “gravitational anomaly” was discovered out near Saturn: a wormhole, presumably placed there by aliens, also presumably the same beings who communicated with Murph using gravity. A dozen habitable planets have been detected on the other side, and a dozen humans sent to explore them. One system has three potentially habitable planets, and it’s now up to Cooper to pilot a ship through the wormhole, figure out which planet is best, and save humanity by giving humans a new home.

At this point the movie pretty much falls apart, both scientifically and in its storytelling. For example, NASA, despite being defunded decades before, somehow has the capability of launching dozens of crewed ships that would cost hundreds of billions of dollars each (and does so, inexplicably—get used to that word—from an underground silo that is literally right next to its work offices). It wasn’t clear why the ships had to have a crew as opposed to being robotic, and the idea that only low-bandwidth data could be sent back (thus precluding getting lots of details about the planets) struck me as a brazen and clunky plot device to get Cooper and his crew to go take a look for themselves.

Cooper successfully pilots the ship through the wormhole (which was lovely and quite well-done, even down to the much-used explanation of how wormholes work borrowed from A Wrinkle in Time), and on the other side he and his crew find the three-planet system, which is inexplicably orbiting a black hole. I sighed audibly at this part. Where do the planets get heat and light? You kinda need a star for that. Heat couldn’t be from the black hole itself, because later (inevitably) Cooper has to go inside the black hole, and he doesn’t get fried. So the planets inexplicably are habitable despite no nearby source of warmth.

At this point I could go on and on (and on and on and on and on … ) with the scientific missteps the movie takes from here. Let me just pick one example, since it was crucial to the movie’s plot but shows how much science was tossed out the airlock.

The Planet That Wasn’t There

It turns out that one of the three planets orbits very close to the black hole, so close there will be severe relativistic effects. Relative to a distant observer, time slows down near a black hole (true), so one hour on the planet will equal seven years elapsing back on Earth. Right away, this is a big problem. To get that kind of time dilation (a factor of about 60,000), you need to be just over the surface of the black hole, and I mean just over the surface, practically skimming it. But because of the way black holes twist up space, the minimum stable orbit around a black hole must be at least three times the size of the black hole itself. Clocks would run a bit more slowly at that distance than for someone on Earth, but only by about 20 percent.

In other words, for the planet to have the huge time dilation claimed in the movie, it would have to be too close to the black hole to have a stable orbit. Bloop! It would fall in.

Also, there’s the problem of tides. One side of the planet is much closer to the black hole than the other side. Gravity changes with distance; the farther you are from the source, the weaker the gravity you feel. The change in the force of the black hole’s gravity across a planet’s diameter is very large, creating a tidal force that stretches the planet. That close to a black hole, the tidal force is huge, mind-(and planet-)bendingly huge. So huge, the planet would be torn to shreds, vaporized.

So if the planet doesn’t fall in, it’s crushed to literally vapor. Either way, there’s no planet.

In the movie, of course, the planet is there. The explorers go down and find it covered in water as well as suffering through periodic ginormous tidal waves sweeping around it. These are unexplained, and I assumed they were caused by tides from the black hole … but that doesn’t work either. That close to the black hole, this inexplicably unvaporized planet would be tidally locked, always showing one face toward the hole. There would be huge tidal bulges pointing toward and away from the hole, but they wouldn’t move relative to the surface of the planet. No waves.

Plot Hole

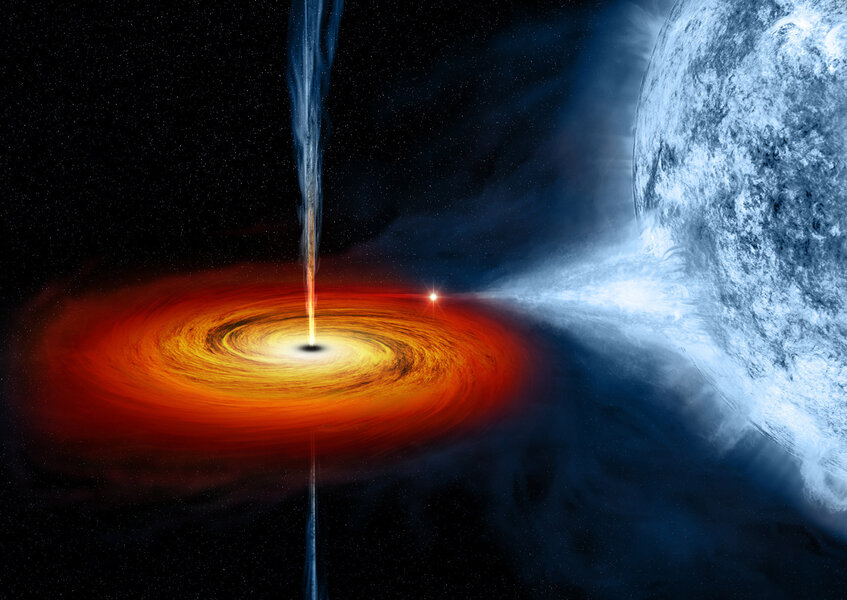

The planet’s very existence is just one example of the scientific stumbles in the movie. There are many others. OK, fine, let me give just one more: the ultimate black hole. For the climax of the movie, Cooper has to fall into it. We see a ring of material around the black hole, presumably the accretion disk: a flat, swirling disk of material that is about to fall into the hole. Because of the incredible forces involved, accretion disks are extremely hot, like millions of degrees hot. They are so brilliant, they can be seen millions of light-years away and blast out enough radiation to completely destroy any normal material.

Yet Cooper flies over one like he’s flying over Saturn’s rings (literally; it was a visual callback to an earlier scene in the movie when they actually fly past Saturn’s rings). In reality, his ship would be flash-heated to a bazillion degrees and he would be nothing more than a thin and very flat stream of subatomic particles. All right all right all right?

Also, for some reason, we don’t see the accretion disk moving; it’s static, frozen, when in reality it would be whirling madly around the black hole. And, due to the tides I mentioned earlier, as Cooper fell in he would’ve been torn apart.

The Play’s the Thing

You may think this is nitpicking, and in a sense it is; I can happily forgive bad science if good science would get in the way of the storytelling. But in this case, the science is critical to the storytelling: This movie is all about black holes. In fact, one of the executive producers is theoretical physicist Kip Thorne (one of the robots in the movie is named KIPP, which made me smile), a scientist for whom I have quite a bit of respect. Thorne’s participation got some press, mostly due to the way black holes in the movie are depicted—and they are visually stunning.

That’s fine, but the thing is, there’s nothing in this movie dealing with black holes you couldn’t find in a college textbook or a Wikipedia page. The ideas of time dilation, warping space, wormholes, even time travel at the end: There’s nothing really new here, and almost all of it has been used in science fiction before. Thorne is a great and very important physicist, and I mean absolutely no disparagement of him, but I’m not sure how the plot of this movie would have been different had he not been involved.

The real problem isn’t with the science, it’s with the story. I’m sure Thorne knew the science was (way) off, but I can guess that director and screenwriter Christopher Nolan chose to ignore those issues in order to advance his story.

Even ignoring the problems with the science, it was the storytelling in the movie that made it nearly unwatchable for me. The characters have very little depth, for one, and the dialogue turned into pure cheese several times.

In a conversation between Cooper and Anne Hathaway’s character about love, she says that love is an artifact of a higher dimension (what does that even mean?) and “transcends the limits of time and space,” as if it’s a physical force—an allusion to gravity, which, critically to the plot, does transcend dimensions, time, and space. The dialogue here was stilted to say the least, and it gets worse when Matt Damon’s character talks about a parent’s love for his children, saying, “Our evolution has yet to transcend that simple barrier.” Who talks like that? The movie is riddled with attempts to be profound, but due in part to the clunky dialogue it just sounds silly.

The plotting was just as laborious. The setup was ham-fisted and plodding; it was obvious immediately that Murph’s “ghost” would turn out to be a black-hole-diving time-traveling Cooper, and that the aliens were in fact advanced humans from the future. They apparently created the black hole and wormhole in the first place, manipulating time and events so things had to unfold the way they did. That part was interesting, though by no means new; Kurt Vonnegut covered this thoroughly in The Sirens of Titan, for example. This might not seem obvious to folks who haven’t watched or read a lot of science fiction, which is fine, but for it to be the Big Reveal fell pretty flat for me.

There were obvious nods to 2001, 2010, and several other movies. And sometimes more than just nods … in an early scene, before he leaves for his space voyage, Cooper decides to give his daughter a gift. It turns out to be a wristwatch, which later in the movie proves critical in her being able to save the world.

I almost yelled at the screen during that scene. In the movie Contact, McConaughey’s character gives Jodie Foster’s character a compass before she goes on her space voyage, and tells her it might just save her life (which it eventually does). The same actor in a similar movie performs the same gift-giving act with a similar gift that turns out to have similar plot results.

There are so many other problems with this movie: characters tossed aside, huge plot points that pivot on coincidence or on one character’s offhand comment that gives another character a crazy-idea-that-just-might-work, plot threads that wind up going nowhere. Like I said, it was a mess.

I’m a scientist, I love science, and I love it when it’s treated well in a movie. But it wasn’t the science that sunk this movie. I’d say that the real, basic problem with Interstellar is that it’s a movie that desperately wants to be profound, but simply isn’t. Had the profundity not been repeatedly shouted at us, it might have worked better.

Ironically, in the end this movie all about gravity doesn’t have the gravitas it thinks it has.