Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Jupiter from below

[Credit: NASA / SwRI / MSSS / Damian Peach]

On February 2, 2017, the Juno spacecraft made its fourth flyby of the mighty planet Jupiter, passing just 4300 kilometers (2700 miles) above the cloud tops. That’s about the same distance as New York City to Los Angeles ... and given that Jupiter is about 140,000 km across, that’s a very, very close pass.

On board the spacecraft is the JUNOCam, an instrument designed to take high-resolution images of Jupiter’s poles as the spacecraft passes above them. The camera was designed specifically for public outreach; the images are made public as soon as they are sent back to Earth. That means anyone can grab them and process them. When this is done by people who are masters of their craft —like Damian Peach— you get the magnificence you see at the top of this article (click that image to embiggen it!).

This is the view of Jupiter’s south pole. It doesn’t look anything like what you expect, does it? I’m used to seeing images taken from Earth, where we are looking “sideways” at Jupiter, down on the equator. That means we see the broad dark belts and lighter zones stretching all the way across the face of the planet, with a few storms (like the famed Great Red Spot) dotting the picture.

You can still see the banding, sort of, in Peach’s Juno image. The pole has a darker, bluer circular area, then a swirly lighter one surrounding it to the north, then progressively paler arcs. From the side, these would make the familiar stripes, but from this angle they take on a peculiar aspect, their true annular nature revealed.

The detail is amazing: You can see storms blemishing the entire planet, and turbulent ripples created as the winds of the planet’s atmosphere distort the more stable flow. Mind you, there’s nothing solid to see here! Jupiter likely has no solid surface or, if it does, it’s buried under tens of thousands of kilometers of atmosphere. On the far right, you can just barely see a red storm right on the edge. That’s not the Great Red Spot; that’s Oval BA, a smaller but similar storm at a latitude just south of the GRS. It’s only about 18 years old; it formed in 2000 when three smaller storms merged.

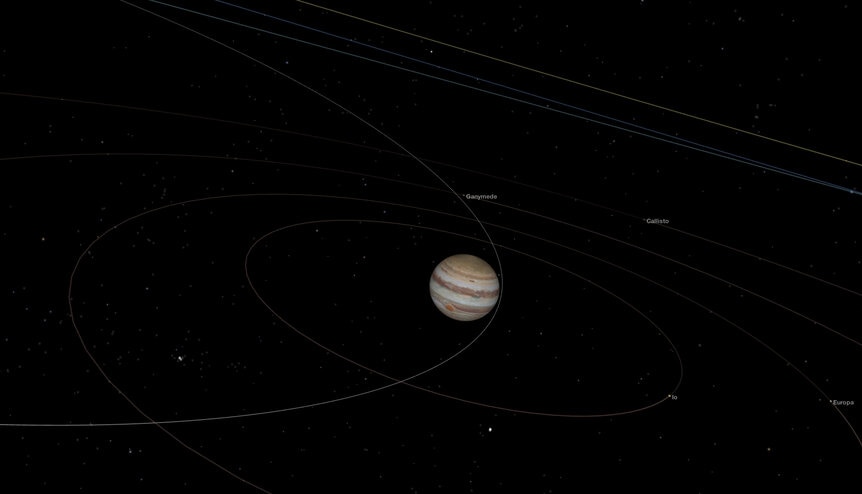

Juno is on a highly elliptical 53-day orbit that takes it over both poles of the planet, then swings it out past the orbits of its four big Galilean moons (Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto). It was supposed to fire its engines after the second orbit to drop it down into a tighter orbit over the planet, but an issue with some valves caused engineers to postpone the maneuver. The next close pass will be on March 27.

I’m hoping the valve issue will be solved soon; these long orbits are cool, but the primary goal of the mission is to be close enough to Jupiter that it passes deep inside the planet’s ferocious magnetic field, mapping it and using it to figure out what’s going on beneath the clouds: The magnetic field is generated deep inside Jupiter, so understanding the magnetic field helps us understand the interior. Also, the different layers of atmosphere inside the planet will tug gravitationally on the spacecraft, nudging it faster and slower as it passes. Those changes in velocity will also be used to indirectly map out Jupiter’s interior. We actually know very little about what’s going on inside the planet! The pressure, temperature, and chemical composition deep inside are hard to mimic in the lab, and computer models rely on observational data for accuracy. Juno will hopefully provide much of that needed information.

If you want to learn more about the planet, watch my episode of Crash Course Astronomy about it.