Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Vampire squid are chill, but their ancestors may have been vicious killers

They lost some of their fire in old age.

When we think of vampires we often think of Dracula, Anne Rice’s famous novels, or maybe even tiny blood-sucking bats. We probably aren’t thinking of cephalopods. While it’s true that vampire squid live out their lives in the perpetual dark of the deep oceans, they’re about as far from blood suckers as any animal can be. Their name seemingly comes not from any monstrous behavior but from their appearance, which is admittedly shudder inducing.

Not only do vampire squid not feast on the blood of aquatic prey, but they don’t even hunt in any conventional way. Instead, they drift peacefully through the deep waters and let food come to them. Mostly, they subsist on marine snow — small pieces of dead material which filters down from above — which they gather with sticky filaments on their two longest tentacles. Their peaceful lifestyle, however, appears to have been a relatively recent evolutionary change.

Alison Rowe from Sorbonne University, and colleagues, recently analyzed the vampire squid’s Jurassic ancestor Vampyronassa rhodanica, and found they might have been brutal killers. Their findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

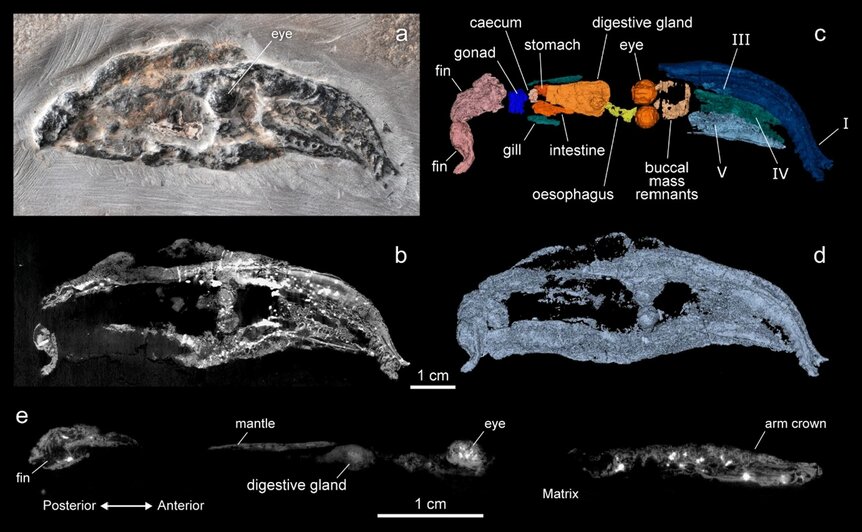

Fossils of V. rhodanica were uncovered in the La Voulte-sur-Rhône site in the Ardèche region of France and are incredibly preserved. The soft tissues of cephalopods don’t typically lend themselves to significant preservation. Most times, the best paleontologists can hope for are impressions in the sediment, but this site is known for preserving specimens in three dimensions. These specimens were first described in 2002, but advances in scientific instruments allowed for a new analysis which revealed much more about the ancient species.

“We utilized powerful X-ray imaging techniques at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (MNHN) in Paris, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York to scan fossil and modern specimens. This allowed us to observe previously unseen internal structures of the fossils, as well as view the external soft tissue anatomy with much better resolution,” Rowe told SYFY WIRE.

Comparing the features of the extinct V. rhodanica and modern vampire squid revealed a host of features in the Jurassic ancestors which aren’t apparent in their living relatives. Key among them were changes in the two longest tentacles. While today they are used to passively gather food from the ocean deep, millions of years ago they were equipped with powerful suckers which were likely used to actively hunt down prey.

“By comparing preserved anatomical features with that of coleoids today — suckers and cirri for example — and knowing how they function now, we can infer how the same features may have been used by the Jurassic V. rhodanica. Based on functional comparisons with modern coleoids, the combination of characters observed in the arm crown of V. rhodanica, as well as their streamlined, muscular mantle, suggest that unlike V. infernalis, V. rhodanica were adapted to a pelagic, predatory lifestyle," Rowe said.

It's not precisely clear what drove the shift from ocean-roving predator to deep sea pacifist, but scientists suspect it may have been due to competition from other species. Understanding their history is further complicated by their unique position in the cephalopod family. The name vampire squid is a misnomer from top to bottom. Not only are they not vampiric, but they’re also not squid.

“It is closer to octopuses than to squids. Like the octopods, it has eight arms, but also two filaments that are developmentally homologous to arms, which makes it somewhat comparable to squid or cuttlefish that have 10 arms. It has cirri on the arms like the octopods incirrate. It has its own characteristics not seen in other modern forms — such as its unique type of sucker attachment, which we have now also identified in V. rhodanica, and its gladius, which is a kind of internal organic shell,” Rowe said.

Getting a clearer look at their ancient ancestors, vicious as they may have been, shines a light on the abyssal darkness of these strange and horrifyingly beautiful creatures. They truly are in 20,000 leagues of their own.