Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

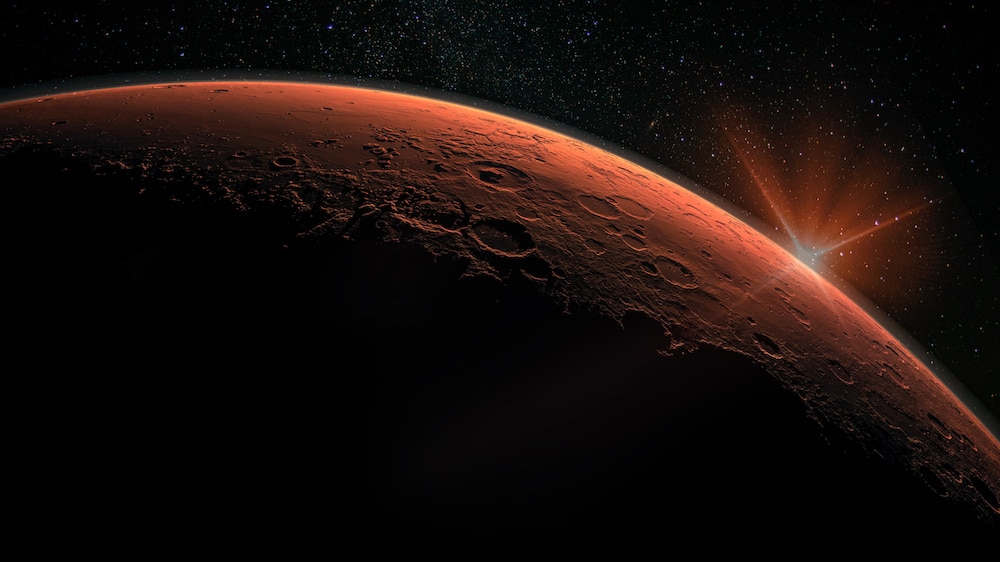

Mars has been getting beat up by asteroids for 600 million years

Even if things had lived there, they probably wouldn't have wanted to hang around.

Nobody knows if anything ever lived on Mars, but nothing would want to hang around on a planet that has been pounded by asteroids for hundreds of millions of years.

Relentless asteroid impacts have scarred the Red Planet. Its surface is obviously pockmarked with craters. What was unknown until now was how often space rocks would crash into it, and for how long those collisions consistently happened. It was previously thought that asteroids would randomly smack Mars in the face, but AI saw through that. Turned out that Mars would have known when to expect them for the last 600 million years, if it was a sentient being.

The visage of Mars is naked, as opposed to Earth, which has plate tectonics going for it. Something like an erupting volcano is going to destroy evidence of collisions by smothering them in magma. Earth’s geological features and vast oceans are also covering up many asteroid acne scars. Now, researcher Anthony Lagain of Curtin University and his team have exposed Martian craters in a study recently published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

“The long-term impact flux of asteroids…is most likely constant over the last 600 million years,” the researchers said, “and that the influence of past asteroid break-ups in the cratering rate…is limited or inexistent.”

It doesn’t help that Mars is so close to the asteroid belt. That’s pretty much asking to get whacked. It also partly explains the suspicion that there were sometimes spikes in crater formation because of debris that was sent flying during a humongous crash, which was believed to have formed smaller craters elsewhere. Lagain and his team proved this wrong by using an AI that had been taught to scour hi-res images and detect visible craters. The algorithm counted those craters and determined that they hardly formed more or less frequently for ages.

Having an idea of how many craters there are on the surface of a body can help with figuring out when geological events happened with Mars, like its past volcanism. Counting craters can also give away the craters’ age and the age of the surface those asteroids hit. Newer expanses of a planet’s surface will have fewer impact craters, since hunks of rock have been bombarding the solar system at a pretty constant rate for billions of years. This may be deceptive because some asteroids may form newer craters that wipe older craters off the face of the planet.

So if the rate of asteroid impacts has been pretty steady for several billion years, what gives? Why was Mars assumed to have erratic spikes in crater formation? Its proximity to the asteroid belt has probably caused some bias, but even that hasn’t resulted in it experiencing drastic highs in crater formation in between what was otherwise a steady occurrence. The AI was able to reveal how huge (or not) the craters were and how many were in a given region, along with when they formed and how often asteroids slammed into Mars. It was all mostly predictable.

This tech could also be adapted to other bodies in space, such as the Moon, which is also naked enough for the algorithm to see everything automatically. You can’t do that so easily by observing Earth from the outside. However, the researchers were able to virtually rewind and reconstruct tectonic plate action from millions of years ago so they could see probable impact craters that indicated when certain features formed on our planet. This told them that there was most likely a cluster of craters that were formed about 470 million years ago.

Jezero Crater might now be the most famous Martian crater, not only because Perseverance is searching it for signs of fossilized microbes, but because it has been proven to be a lake. Maybe some of the others also held water — and maybe even life.