Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Memories of the Blue Snowball

I was procrastinating the other day — shocker, I know — and tooling around Instagram to see what there was to see.

An astonishing number of astrophotographers post their work there (and a lot of content scrapers do as well, which is extremely irritating), as do some national observatories and international science collaborations.

NASA does too, of course, and when I saw this image I gasped, then smiled, then chuckled out loud.

My first reaction was due to the beauty. The second was when I recognized what it was. The third was when I remembered I’ve observed this object.

It’s NGC 7662, a planetary nebula: The gas blown out by a dying star, which is lit up by high-energy ultraviolet light from the star itself. Stars like the Sun eject their outer layers over millions of years as they die, and various conditions can shape those winds into beautiful and eerie shapes. When the layers are all ejected, they reveal the hot, dense white dwarf core, which is what excites the gas and causes it to glow. NASA’s page about this image of NGC 7662 has some more info.

NGC 7662 is relatively bright and located in the constellation of Andromeda, making it a moderately easy target for small telescopes. In this case, Hubble’s view shows the central white dwarf, and the gas blowing away from it. The reddish bits are called FLIERs, for Fast Low-Ionization Emission Regions, which means gas moving rapidly where the atoms in it have had one or two electrons removed from them. In this case the glow is due to singly-ionized nitrogen. It’s not clear what causes FLIERs, though many planetary nebulae have them.

To be honest, I’m not sure I understand the color scheme in this image here. Generally hydrogen gas is shown in red, but as far as I can tell it’s displayed as blue here. Another famous shot of this nebula shows it as green! It goes to show you that color in astronomical images you see online or printed in books can be somewhat arbitrary. The person creating the image can pick what color represents which filter used, and sometimes it’s done for aesthetic reasons more than scientific.

The funniest bit: By eye through a telescope the nebula appears bluish, due to oxygen in the gas. It’s even nicknamed the Blue Snowball nebula! Maybe that’s why this image shows it as blue.

Back in the day, when I was working on my Master’s degree, I studied planetary nebulae. Surrounding some of them is a giant halo of gas, usually spherical, which is the first gas expelled by the star when it just starts the final cycle of its life. I observed a few using UVA’s 1-meter telescope at Fan Mountain, and wound up concentrating on NGC 6826, the halo of which was bright enough to spot.

I observed a half dozen planetaries in total, including NGC 7662, which isn’t too far in the sky from NGC 6826. I took a pile of images but couldn’t see the outer halo, so I dropped it as a target we could measure. Ironically, I learned later it too has a giant halo, and we actually could detect it in our data! It was too faint to actually do anything useful with, but if I had had more time I would’ve gone back and taken deeper images. Ah well.

The image of NGC 7662 here by Hubble only shows the inner region; the outer halo is much larger and too big to fit in this field of view. You can find images of it by searching online (Derek Santiago’s image is especially nice, and Courtney Seligman has a good one too).

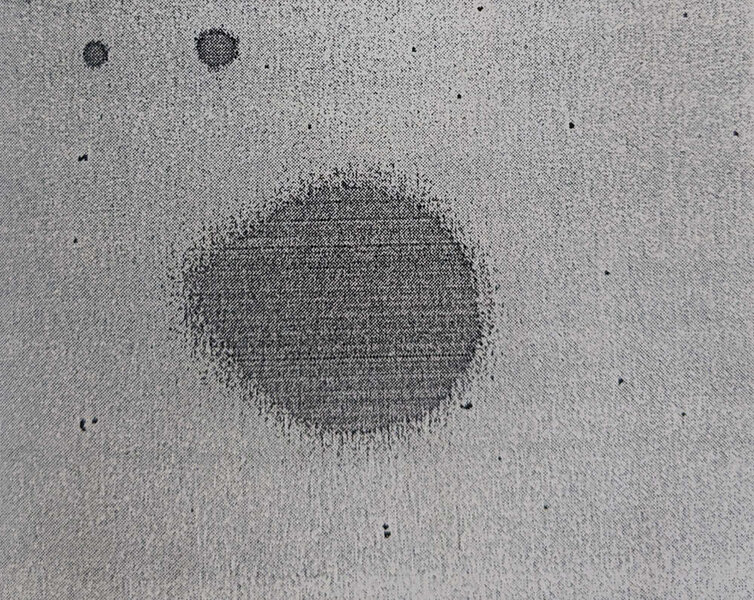

That’s why I chuckled when I saw the Hubble image. I pulled out my old Master’s thesis, and found my image of NGC 7662. This was in 1989, so we didn’t have a lot of fancy digital printing available; for the thesis I literally printed out a copy of the image and stuck it on a page. I couldn’t balance the image brightness at all, so it looks like a vast black blob with stars in the background (black because it’s routine to display astronomical images as negatives; the eye is better at seeing contrasting detail that way).

Hubble launched around the time I got my Master’s degree, and I wound up using Hubble data of the gas around a supernova to get my PhD (which, coincidentally, was very similar to a planetary nebula in many ways). At the time I remember thinking it would be fun to observe some planetaries with Hubble, but was a bit busy with other work to ever talk to other astronomers about it.

Others had the same idea, of course, and now Hubble shots of planetaries are staples of websites and classrooms. They are gorgeous almost beyond anything else Hubble has peered at, and that’s a pretty damn high bar.

Still, in the summer months when I haul out my own ‘scope — sometimes when I show others the sky, too — I will inevitably point it at the Ring Nebula, the Dumbbell, and other bright planetary nebulae. Maybe one day I’ll see if I can spot NGC 6826 and 7662 through the eyepiece. I am not overly prone to nostalgia, but sometimes, y’know, it’s just nice to see old friends.