Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The Milky Way's Old (and Huge) Faithfuls

The Milky Way galaxy—our home galaxy—is erupting. Two monumental geysers are blasting out of its heart in opposite directions, and astronomers recently got the clearest view of them ever seen.

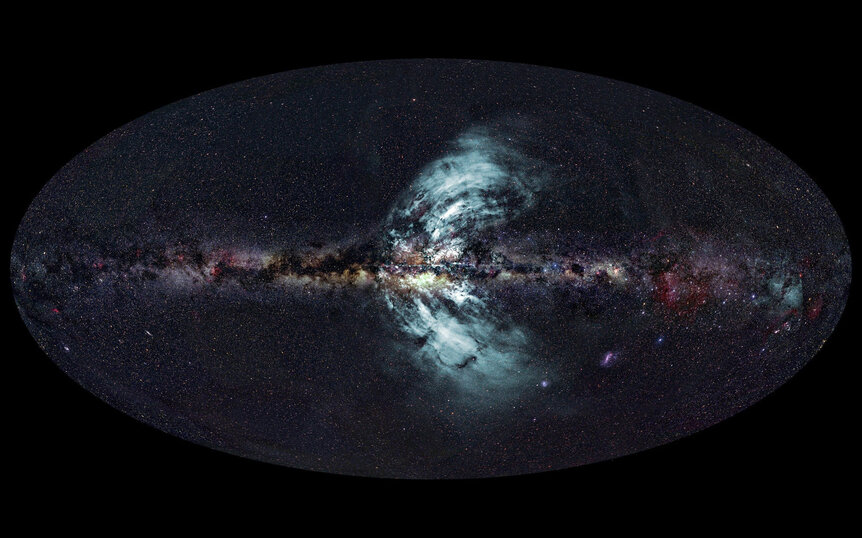

The image above shows the Milky Way in visible light, as we see it on a very dark night—stars, gas, and dust strewn across the sky. Superposed on that is the radio emission from those vast winds of material blasting outward (which is invisible to the eye; it's colored blue so you can see it). Those radio waves were detected by the Parkes radio telescope in Australia. These winds been seen before using both radio telescopes and Fermi, an orbiting observatory that detects gamma rays (the highest energy form of light), but only at low resolution. Until now they haven't been mapped so clearly and in such detail.

The scale of this image is difficult to grasp. I’ve cropped it here to let you see the structures, but if you look at the original image it shows the whole sky … and you can see these eruptions of matter are so vast they stretch across two-thirds of the entire sky!

I’m actually rather stunned at this. If you had radio-vision, and you could see these streams of matter, you’d have to physically turn around to see the whole thing end to end. In real numbers, the material is about 50,000 light years long—half the length of the galaxy itself—and is rushing away from the center of the galaxy at a mind-numbing 1000 kilometers per second!

When I read that, the hair on the back of my neck stood up. My first thought was, “What the frak could power something that vast?”

And then I found out: The geysers contain the energy equivalent of a million exploding stars!

At that point I may have blacked out for a moment or two. If you want to know what humbles an astronomer, then this is pretty much your go-to scenario.

It’s hard to express the colossal nature of this. Think of it this way: Take all the energy the Sun emits every second (enough to power the entire Earth’s needs for nearly a million years). Now multiply that by 31 million, the number of seconds in a year. Now multiply that by 10 billion, the numbers of years the Sun will be around. It’s a huge number, staggering, and that’s still only about 1% of the energy output of a single supernova. That means these geysers contain a hundred million times the Sun’s entire lifetime supply of energy.

See? That’s why I was overwhelmed.

I’ll note that these geysers present no danger at all to us here on Earth. If they did, we’d have been zapped a long time ago; this structure is pretty old, millions of years old at least. But we’re a long way from the action; the core of the galaxy, where the geysers are generated, is 26,000 light years away, and the material itself is not headed anywhere near us. We’re safe.

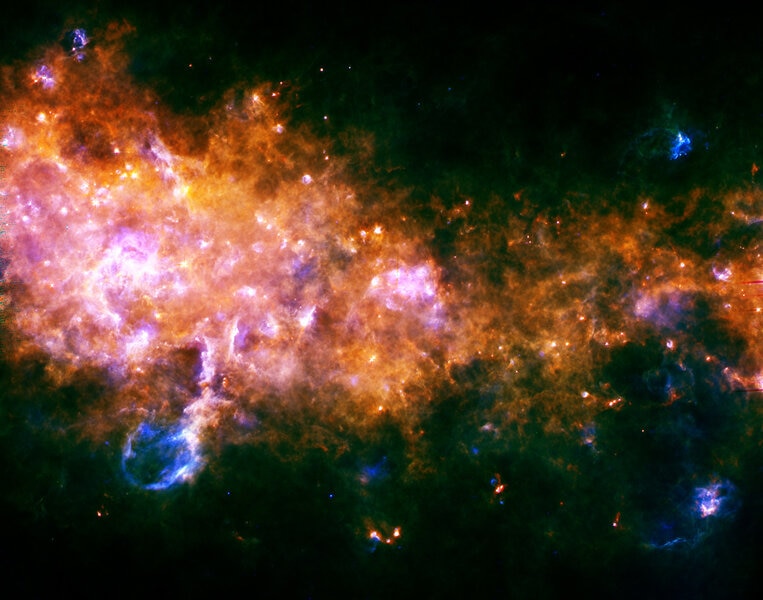

So still, what could possibly generate this much energy? For a long time it was thought to be the supermassive black hole we know exists in our galaxy’s center; matter falling in can be ejected away at high velocity. Another competing idea was that vigorous massive star formation over millions of years would generate huge winds of material, boosted even more when those stars died as supernovae. We know this happens on a smaller scale in the galaxy; bubbles of gas and dust erupting outward have been seen before, as in this image from the Herschel space telescope:

At the lower left is a small herniated region (colored blue in this false-color far-infrared image) caused by supernovae and the winds from new stars blowing material out of the galaxy. Even though this is pretty big on a human scale (many light years across), it’s peanuts compared to the Parkes observation. Still, the idea is the same.

And the new Parkes observations finally do resolve this. As the material blows out from the galaxy it carries with it a magnetic field. Careful analysis of the effect of that field on the material using the Parkes data shows the energy source to be star formation, and not winds from the black hole. The shape and structure of the geysers indicate there must have been several different episodes of star formation, in fact, and not just one long, continuous event.

I’ll note I’ve been reading about these competing ideas for a long time, and the debate has been pretty strong. Until now, it wasn’t clear which was right, so it’s nice to see this resolved.

And it’s amazing, too: It’s incredible to think that something with so much power could have been hiding from us for so long; it’s only because it’s spread out over so much sky that we missed it.

Such an incredible image, on such a scale! It’s wonderful to know that we can learn so much about our own home. Even better, it reminds us that we still have so much more left to learn.

That’s yet another reason I love science so much. It’s a magnificent puzzle that never ends. There's always another piece of it waiting to be found around the corner, and there's always more to learn.

[Update: I got a note from my friend Carolyn Porco—imaging team leader for the Cassini Saturn mission—saying that technically, the term "geyser" is only used to describe eruptions of water. She should know, since she studies the geysers at the south pole of Saturn's moon Enceladus! I'll note I use the term here as an analog, a metaphor if you like. There are many terms for such events—jets, bubbles, cavities, and so on—but none seemed to fit like "geyser." This is a common problem in communicating science; being technically accurate while still being able to actually describe things to people who may be unfamiliar with the science. I apologize for using any misleading terms, and I'm happy to hear of any better ones!]