Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The most ancient reptile still alive crawled out as far back as 190 million years ago

All its friends are extinct.

It looks like a lizard. It walks like a lizard. It sunbathes and lounges and eats like a lizard, but the tuatara is not a lizard.

What the tuatara actually is goes as far back as the dawn of the dinosaurs. This mysterious creature (which is also one of the poster animals for New Zealand) belongs to a group of reptiles known as sphenodontians, which are thought to have spawned 230 million years ago, around the same time monsters that were somewhat related to it started roaming the Earth. A fossil of an extinct sphenodontian has revealed that the linage of the tuatara itself has now been found to reach almost that far back — 190 million years ago.

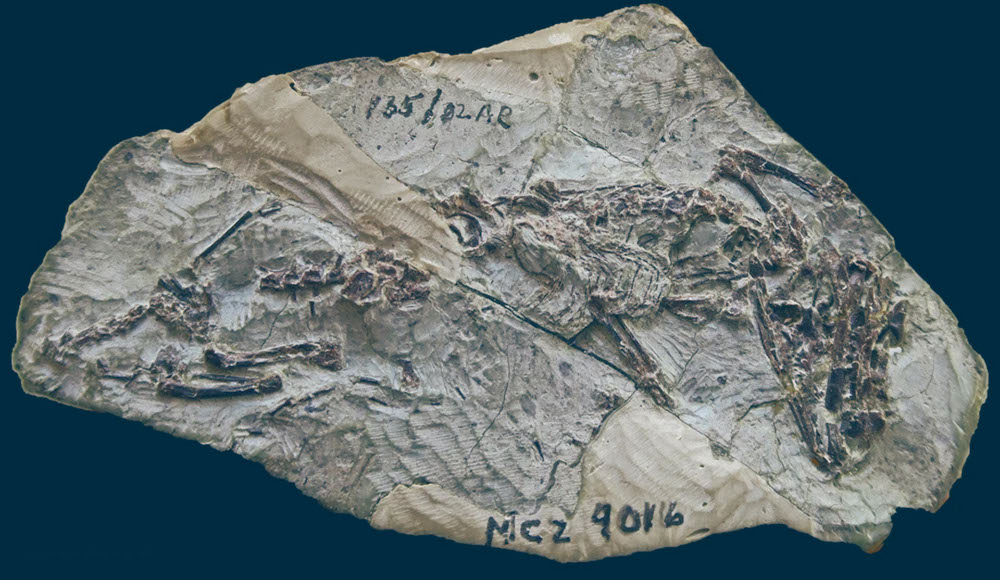

Sphenodontians were creeping around during the Mid to Late Triassic, and are thought to have possibly emerged even earlier than that, some 259 million years ago during the Late Permian, and held on for a while. Now only the tuatara is left. Paleontologist Tiago Simões was part of the team that identified the amazingly preserved fossil (above) and others as belonging to the new species, tuatara predecessor Navajosphenodon sani. He led a study recently published in Communications Biology. Why no other sphenodontians still exist remains unknown.

“We do not have the data yet to know how they managed to survive so long with such restricted diversity,” Simões told SYFY WIRE. "Without enough fossils, we cannot yet know where they were living and how they got to New Zealand at some point during the last 66 million years.”

Navajosphenodon sani is the oldest known direct ancestor of the tuatara. The nearly complete fossil that was unearthed is the holotype, or single specimen on which the identification of this species is based. More scattered fossils of Navajosphenodon teeth and bones were also found in the same formation, the Kayenta Formation in Coconino County, Arizona.

To see how this species of sphenodontian was related to others without any surviving DNA, Simões and his team used several type of phylogenetic analysis. These methods figure out how organisms evolved and the evolutionary relationships they have to other organisms that all came from a common ancestor.

Something that might have led to the tuatara being the sole survivor is the exceptionally slow evolution of its genome. You are pretty much looking at a reptile whose ancestors didn’t change much as other prehistoric creatures emerged and morphed and ruled the world before they died out, and kept crawling on as entire human empires rose and fell. The Navajosphenodon fossil is evidence that the tuatara’s body plan hasn’t really needed any upgrades in ages.

“One of the special things about tuataras is the way they chew,” said Simões. “They have a precise mode of dental interlocking and temporal bones designed to reduce stress when biting hard. Navajosphenodon shows both mechanisms had already evolved by 190 million years ago.”

If something works out evolutionarily, an organism will just go with it. This could explain why both the morphological and molecular evolution of the tuatara have been so slow. Morphology, which encompasses the inner and outer structures of organisms, such as the tuatara’s jaw, usually evolves as developmental genes change. Sometimes mutations can also cause a sudden leap in morphological evolution. Molecular evolution is involved with changes on a cellular level, including those that affect DNA, RNA, and the proteins they are made of.

However, never mind that there are no other living species of sphenodontians, but there is only one species of tuatara, Sphenodon punctuatus. It never diversified beyond that. Simões thinks most sphenodontians, including those that would give rise to the tuatara, stayed in southern continents for some reason, which might have had something to do with the lack of diversification. Navajosphenodon may be a prehistoric relative, but it is not another kind of tuatara. This creature is what it is — and no one knows why.

“We know there were slow rates of evolution in sphenodontians, especially in the lineage leading to the modern tuatara,” he said. “Yet, it's a mystery why they remained so restricted in diversity for so long.”