Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

NASA just launched a yeast-filled generation ship to test the effect of space on biology

Bread. Beer. Space. There's nothing yeast can't do.

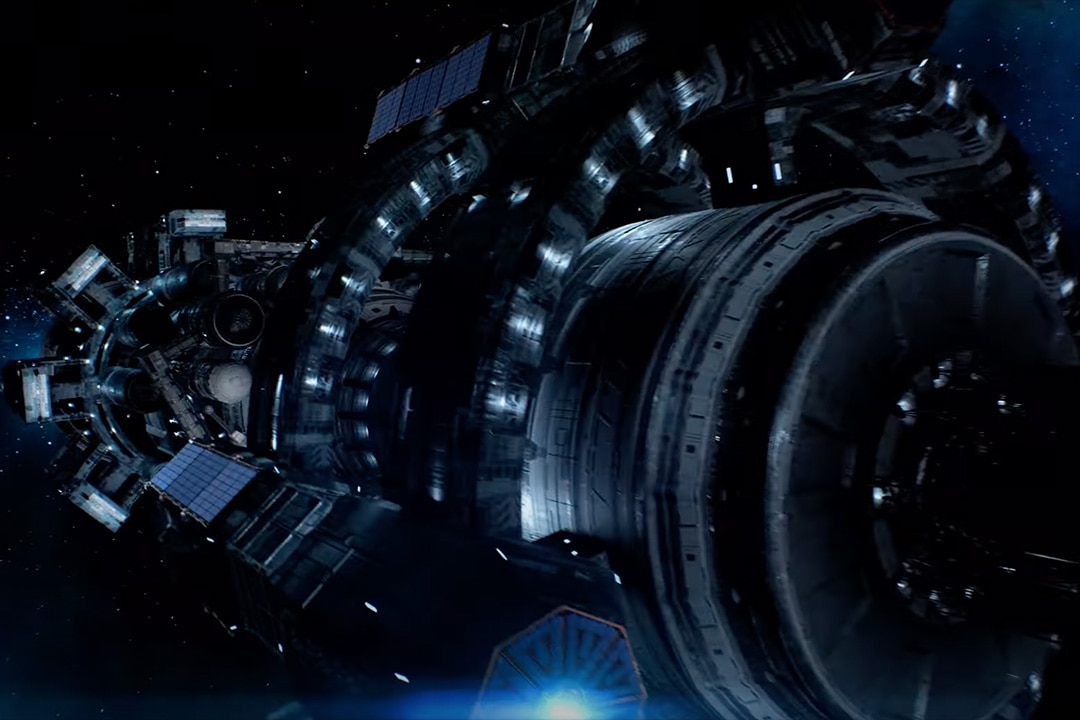

From Dean Devlin, the creative mind behind science fiction classics like Independence Day and Stargate, comes humanity’s next struggle for survival in the vastness of space, The Ark. The upcoming SYFY series (debuting February 2023) takes viewers on an interstellar adventure one hundred years in the future. A century from now, the Earth can no longer support humanity and we have taken to space aboard a ship called the Ark One, in search of a new home.

The challenges that face the crew of the Ark One are many, varied, and deadly. That’s as it should be. If we really wanted to send a group of people toward the stars, on a ship that would bear them to a new planet, we’d have to make plans for generations of their descendants to live, reproduce, and die on that ship. The entirety of their lives would take place in transit, without the protection of a planet. It sounds like a far-flung sci-fi fantasy, but without the benefit of faster-than-light travel, It’s the only way we’re getting out of our own neighborhood. The trouble is deep space presents some additional challenges we don’t really have to deal with closer to home. If we ever want to build a generation ship, or even send humans to Mars, we’ve got a lot of work to do.

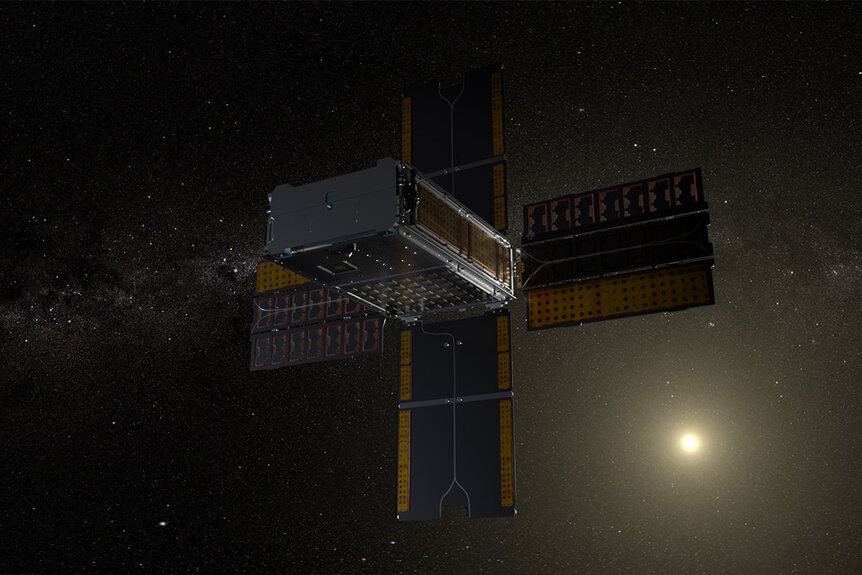

That work began in earnest a few weeks ago, thanks to a shoebox sized cube satellite called BioSentinel, which stowed away aboard Artemis I. Inside that small satellite is a collection of yeast which is, right now, in the midst of a long-term deep space mission investigating the impact of cosmic radiation on living organisms. To be clear, humans are doing the investigating. The yeast is just yeasting… IN SPAAAACE!

We have maintained a continuous human presence in space for more than 20 years, thanks to the efforts of astronauts and cosmonauts aboard the International Space Station. But even that remote port of call, 250 miles above the planet’s surface, is relatively protected by the Earth’s magnetic field. That field extends about 40,000 miles above the planet, which might sound like a lot, but it runs out quickly. When astronauts board Artemis II on a trip toward the Moon, they’ll run out of magnetosphere with only about a sixth of their trip behind them.

RELATED: What we know about the damaged Soyuz capsule and what's next for the crew?

If we’re going to get people to Mars, or to a distant star, we’re going to need to bring our own protection against cosmic radiation. In order to do that, we need to better understand what we’re up against. BioSentinel will carry the yeast more than a million miles away from Earth, well beyond the influence of its magnetosphere, and park itself in orbit around the Sun. It will stay there for at least 18 months while scientists observe the yeast for any changes.

Yeast cells are relatively similar to human cells, including DNA which can be damaged by radiation, and we expect them to undergo the same sorts of damage and repair processes humans might experience in the same conditions. Those observations officially kicked off Dec. 5, when BioSentinel was 655,730 miles from Earth. You can follow along with the satellite’s journey using NASA’s Eyes on the Solar System tool.

Not only will BioSentinel show us what happens to individual yeast cells experiencing extended exposure to cosmic radiation, but it will also show us how generations of yeast are impacted by the novel environment. The doubling time of yeast is about 90 minutes, which means they’ll go through nearly 9,000 generations over the course of 18 months.

For comparison, MIT estimates it would take 6,300 years to get to Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to the Sun, using current technology. Assuming an average of 25 years per generation, it would take us about 250 generations to get there. Take that, yeast!

When we do finally set boots down on Mars or send our first envoys toward the stars, we’ll have to add yeast next to Gagarin and Armstrong on the list of names that helped us get there.

Looking for more deep space adventures before The Ark sets sail in February? Join the crew of Space: 1999 as they ride a rogue Moon into the abyss; the complete series is streaming, right now, on Peacock!