Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

New Data Show Mercury Almost Certainly Has Buried Ice at Its North Pole

New data from the NASA space probe MESSENGER indicate that Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun, almost certainly has water ice buried beneath the surface at its north pole!

I know, it sounds completely crazy, but hang tight. It all makes sense.

Mercury is a mere 58 million kilometers (36 million miles) from the Sun and has a surface temperature of 430 degrees Celsius (800 degrees Fahrenheit). But thatâs a maximum temperature. In shadows that temperature can drop drastically.

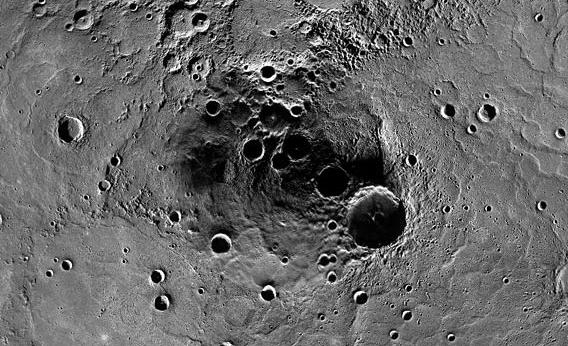

At Mercuryâs north pole there are some deep craters. For example, the large crater Prokofiev is the deepest crater measured on Mercury so far. Itâs over 110 kilometers (68 miles) across. Because the crater is deep, and the Sun never gets very high off the horizon at the pole, there are parts of the crater floor that are permanently in shadow; they literally are never illuminated by the Sun. Those spots can be very cold; well below the freezing point of water. There are actually quite a few spots like that at Mercuryâs north pole.

Over many years, astronomers have sent pulses of radar at Mercury to map its surface. They were surprised to find that there were spots near the north pole where the radar pulses were reflected back to Earth far more strongly than expected from mere rock. Ice, literally frozen water, is a good reflector of radar, so it was hypothesized that there might be ice there.

The MESSENGER space probe has been orbiting Mercury since March 2011. It has a piece of equipment called a neutron spectrometer, which measures neutronsâsubatomic particlesâblasted off Mercury by cosmic radiation. Itâs complicated, but the speed of neutrons coming from Mercury can be changed if thereâs hydrogen present, and thatâs just what has now been seen at Mercuryâs north pole. Combined with the radar data, thatâs strong evidence that thereâs water thereâwater is made of two atoms of hydrogen and one of oxygen.

Furthermore, the bright spots seen by Earth radar together with the neutron data from MESSENGER were superposed on a map of Mercury made using MESSENGERâs cameras, and all those spots correspond to deep craters. And the final bit of evidence that makes this so convincing: thermal maps made using infraredââheat vision,â if you likeâshows these very same spots are ones that stay permanently cold!

Thatâs what this picture shows: Red spots show permanently shadowed (and therefore cold) spots at Mercuryâs north pole, and yellow shows where the radar from Earth indicates ice. Note how strongly they correlate to craters!

The ice appears to be buried a few dozen centimeters beneath the surface, and may be from half a meter to 20 meters (20 inches to more than 60 feet) thick. That adds up to an amazing 100 billion to one trillion tons of ice!

And weâre not done: Further observation indicates that some regions in these craters are intrinsically dark, and others bright. The best explanation of this is the presence of organic, that is carbon-based, molecules on the surface. This does not mean life! But carbon molecules are very interesting because we know comets (and some asteroids) have lots of organic compounds like that, as well as water ice. And this is starting to give us a complete picture of whatâs going on.

Comets hit Mercury, and have been doing so for billions of years. Most of the water ice in a comet impact gets blown back into space or destroyed by solar radiation over time. But if some of that cometary material settles down in Mercuryâs shaded north pole crater areas, it can survive, protected. Over the eons itâs built up, and now with our technology we can actually see it!

This is simply amazing. The irony of finding water ice on such a hot planet is obvious, but also an indication that water is everywhere in our solar system, from close in to the Sun to the farthest reaches we can see, billions of kilometers out past Neptune. We know our kind of life is based on carbon and needs water. I donât think weâll find life on Mercury, but what this says to me is that the basic ingredients of life can survive formidable circumstances. And that makes me wonder even more if life can get a toehold (pseudopodhold?) in places where we might have earlier thought it impossible.

Mercury is an unlikely place to teach us about life in the Universe. Still, perhaps itâs good to remember that life itself may seem unlikely at first, but the conditions for it to arise may be common in the cosmos.