Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Talk about bug-eyed, this critter fossilized in amber could see in 360 degrees

Watching. Always watching.

As Jurassic Park opens, before the viewers or the characters ever set eyes on a dinosaur, we’re taken first to an amber mine in the Dominican Republic where workers are dutifully digging into the sediment in search of fossilized tree sap. That amber proves critical to the functioning of the park and it’s an important source of preserved specimens for real-world paleontology as well.

Trees regularly release sap or resin, allowing it to flow over their bark. It helps to protect them by filling in gaps and creating a barrier between them and the outside world, especially when they’re injured. Once it stops flowing and fills in any creases, sap hardens and remains in place. Sometimes, over millions of years, that sap fossilizes into amber. And, if we’re lucky, it rolled over a small animal during its release and trapped them, nearly perfectly preserved, inside.

These amber deposits provide paleontologists a novel window into extinct animals, preserving them with much higher clarity than is provided through conventional fossilization. Burmese amber, one of the types of the most interest, comes from the Hukawng Valley in the southwest of Maingkhwan in the Kachin State, and nearby areas of Myanmar.

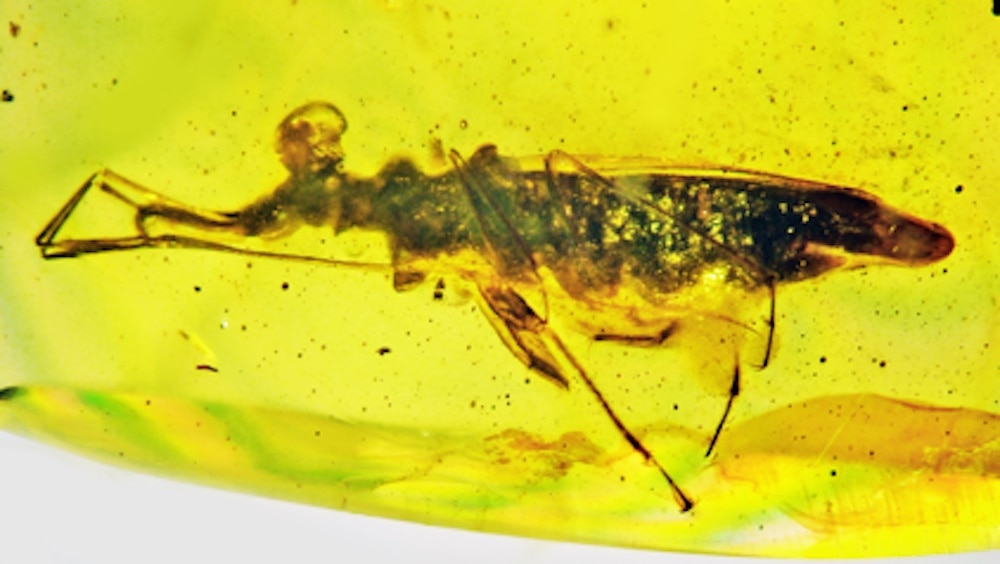

There, amber miners uncovered a previously unknown insect which lived roughly a hundred million years ago in the mid-Cretaceous. The specimen was then sold to scientists including George Poinar from the Department of Integrative Biology at Oregon State University, who studied the trapped bug in collaboration with partners from Berkeley and the Eötvös Loránd Research Network, revealing some truly bizarre traits. The results of that work were published in the journal Palaeodiversity.

“It underwent a detailed morphological study, which revealed the unique eyes and the sticky front legs, as well as many other unique features,” Poinar told SYFY WIRE.

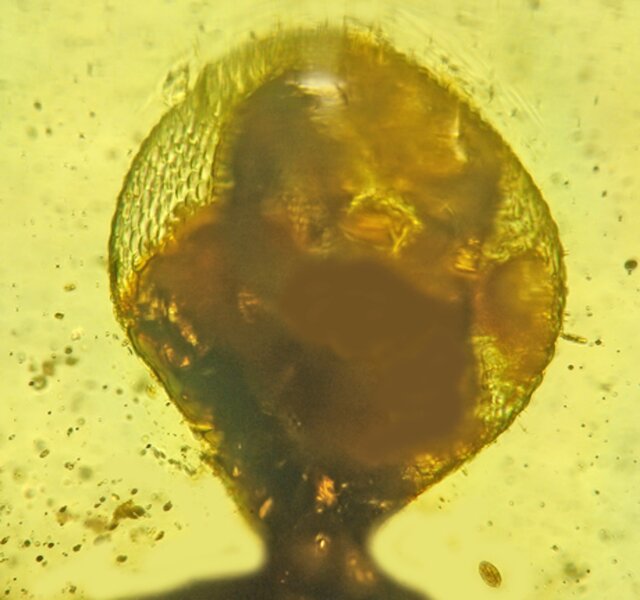

The specimen, dubbed Palaeotanyrhina exophthalma, is roughly 7 millimeters long and has relatively large, bulging eyes sticking out from stalks at the front of the head. Those eyes would have provided it with an incredibly complete visual field, allowing it to see most if not all of its surrounding environment.

“Since they protrude above the head, I think they provided a 360-degree view of their surroundings. This would allow the bug to more easily detect prey items and also larger predators that could harm them,” Poinar said. For comparison, our own eyes provide us a visual field roughly half that size. We’re unable to see anything coming at us too far to the side or from behind. P. exophthalma wouldn’t have had that problem.

Nature is always red in tooth and claw, but that was terrifyingly illustrated during the Cretaceous when massive predatory dinosaurs like the T. rex roamed the world, chomping through the flesh and bone smaller dinosaurs unlucky enough to cross their paths. We easily imagine those bloody battles when we imagine the world 100 million years in the past, but we often forget that similar battles were carried out on a smaller scale in the invertebrate world.

P. exophthalma was a well-evolved predator, stalking other creepy crawlies on the trunks and branches of Cretaceous trees, and its impressive eyes weren’t the only tool in its arsenal. Analysis of the fossil revealed a sticky trap built into a sheath on the final leg segment of the front tarsus which could have grabbed hold of prey like a piece of handheld fly paper.

“That is very curious. A sticky material was manufactured by glands in the front legs. This material essentially coated the tips of the front legs, allowing the bug to snatch up small prey items. Some bugs today coat their front legs with tree resin to accomplish the same result,” Poinar said.

While P. exophthalma does share some traits with existing bugs — notably, the assassin bug which has a tendency to sneak up on spiders and calm them with gentle taps before striking — Poinar noted that it’s not directly related to any living modern bug. Instead, it is an example of something that was wonderfully adapted for the time in which it lived but fell to extinction, like so many other species, as the world changed.

The first part of its name, Palaeotanyrhina, reflects that reality by placing it into its own extinct family. As yet, it is the only member. There’s something almost poetic in the knowledge that P. exophthalma used a sticky resin to trap its prey before falling victim to the same tactic from the trees on which it lived. In doing so, it allowed us to see it with almost as much clarity as it could see its own environment.