Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

New research points toward "no" on arsenic life

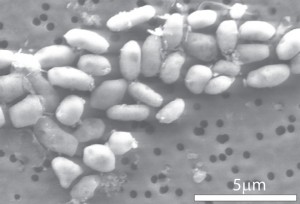

In December 2010 a team of researchers, with NASA's blessing, announced a truly remarkable result: bacteria that lived in California's Mono Lake not only thrive in the arsenic laced water, but have incorporated arsenic into their biophysical processes. This was a big deal, since it wasn't thought that this was possible (while arsenic has similar properties to the biologically-necessary element phosphorous, replacing one for the other had never been seen before in nature).

In December 2010 a team of researchers, with NASA's blessing, announced a truly remarkable result: bacteria that lived in California's Mono Lake not only thrive in the arsenic laced water, but have incorporated arsenic into their biophysical processes. This was a big deal, since it wasn't thought that this was possible (while arsenic has similar properties to the biologically-necessary element phosphorous, replacing one for the other had never been seen before in nature).

However, the team found their findings immediately under fire by other biologists. Here is my initial report on the press conference announcement, and here's my followup after severe doubt had been cast on the findings, and a third article from a few months later. Basically, the team's methods, analysis, and results were found to be lacking, and two other groups of biologists started up their own investigation to replicate the research.

Today, Science magazine published the results. Arsenic? Nope. One team found that while the bacteria thrive in arsenic-rich water, there must be some phosphorus present for it to live (indicating the cells had not replaced As with P). The second team found no evidence that arsenic had been incorporated into the cells' biochemistry.

This is disappointing but not unexpected news.

When NASA held the press conference, a lot of media - including me - were very excited. We trusted NASA that the work had been vetted by other scientists and was legit. While I think the work was done honestly - that is, the research team didn't cheat or anything like that - it's looking like they jumped to their conclusion, and the initial peer review process didn't work as it should have.

But there's more to it than this. The members of the original team are sticking by their results, saying that not finding something may not indicate it's not there - in other words, the followup research may have missed the arsenic. While that's possible, it comes across as stubbornness in the face of contradictory results. That is simply an interpretive opinion by me, but it does seem odd that they claim the new results actually don't refute their original findings. It looks to me (though I'm no biologist) that they certainly do.

[UPDATE: Here's a good article by my pal Dan Vergano at USA Today about this, and he also got great quotes from both the original researchers and the other teams.]

Discover Magazine's The Loom blogger Carl Zimmer - who has always been very skeptical of the results - live-blogged this new announcement, which makes for fascinating reading. There are some great quotes in there, and it's worth your time to read through. DM's 80 Beats blog also has relevant links about all this.

There are several lessons I think we can pull from all this:

1) The scientific process works, but there's friction with the journalistic process. Of course, we've known that for a while!

2) Just because there's a press conference, and just because it's backed by NASA, doesn't mean the results are true. That's a hard-won thought for me, but one I take seriously.

3) The thing we shouldn't forget: all the biological research teams do agree that the bacteria in Mono Lake actually do thrive in those arsenic-heavy waters!That itself is an important scientific result. While those bacteria may not incorporate the poison into their own biochemistry, it shows again that life can adapt to extremely difficult and even previously-thought toxic circumstances. The ramifications for astrobiology (finding life on other planets) are still important, and this gives us strong and critical insight into the very chemistry of nature itself.

Related Posts:

- NASA's real news: Bacterium on Earth that lives off arsenic!

- Independent researchers find no evidence for arsenic life in Mono Lake

- Arsenic and old posts

- Arsenic and old Universe