Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Get over here! Giant-clawed sea scorpion ruled the Silurian

The Silurian was metal.

The Silurian, spanning from 443.8 to 419.2 million years ago, was a period of massive evolutionary change on Earth. The landmasses were vastly different, comprised of a few supercontinents which would later come together to form Pangaea.

Landmasses were low with rising sea levels, which provided a swathe of shallow oceanic environments. These new niches, rich in sunlight, were a perfect home for the emergence of all sorts of new life. Plants and animals were just beginning to get a toehold on land, but all the most interesting things were happening in the water. Coral reefs were abundant, and the seas were dominated by invertebrate animals, the most impressive of which were the mixopterids.

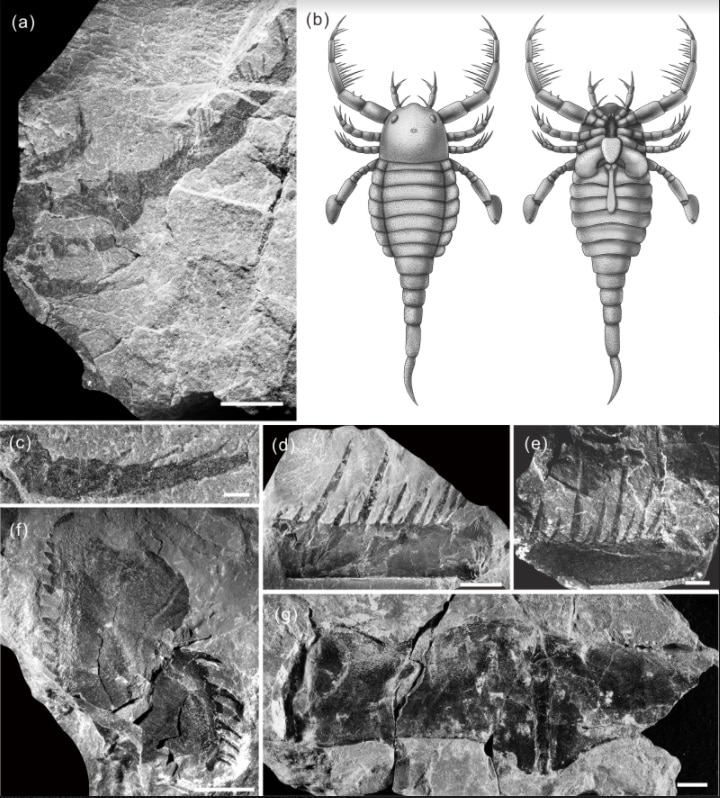

Very few examples of these animals –– commonly known as sea scorpions, owing to their superficial resemblance to the modern animals –– have been discovered. For a long time, they were known only by four species, discovered in Norway, New York, Estonia, and Scotland. All of which were part of the paleocontinent of Laurussia during the Silurian. Until recently, all known mixopterids derived from Laurussia, but a recent discovery in China proved they were more prolific, swimming the seas of ancient Gondwana as well.

Han Wang, graduate student at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and colleagues, described two specimens of a new species found in Xiushan and Wuhan, China. Their findings were published in Science Bulletin.

“The finding of Terropterus xiushanensis represents the first mixopterids in Gondwana, and also the oldest mixopterids,” Wang told SYFY WIRE.

These early arthropods are related to all manner of modern arthropods including arachnids and horseshoe crabs. It’s likely their descendants were among the first terrestrial animals, and they might have been semi-terrestrial themselves. Though, given the large size of their bodies, it’s likely they would have preferred the water, only stepping onto land occasionally.

These new specimens were sufficiently different to be considered a new species, unsurprising considering the difference in locality. They differed from previously described sea scorpions primarily in the construction of their limbs and spine patterns.

Terropterus xiushanensis has specialized limbs, the largest of which are covered in spines likely used for capturing prey. Similar structures can be seen in the modern whip spider (shown below), where they’re used to latch onto prey, preventing its escape.

While the whip spider is frightening enough despite its moderately small size, terropterus would have been far more terrifying to meet during a day at the beach. The two specimens measure at 40 cm and 100 cm (15 and 39 inches) respectively, and it’s possible they were juveniles, hinting at much larger adults. Other species have been measured at up to 190 cm (75 inches). Already, this makes them among the largest, if not the largest sea scorpions discovered.

The first fish with jaws did appear in the oceans during this period, but they were outliers. Most of the fish during the Silurian were jawless and similar to modern hagfish or lampreys. Those ancient oceans were filled with a menagerie of horrors, all of which bent to the will of the sea scorpion.

“They would have been living in shallow seas, playing an important role as top predators. They may have fed on jawless fish,” Wang said.

If their massive, spiny claws weren’t enough for them to dominate the Silurian seas, it’s also possible they had a weaponized telson (stinger) much like modern day scorpions, which they would have used to hunt prey animals in the water. The team did find a preserved telson in one specimen, but it’s unclear if they were actually used in this way.

This discovery expands the domain of sea scorpions both geographically and chronologically, reinforcing the notion that there is much yet to discover. It also reminds us to be grateful that we live during a time when scorpions aren’t the size of large dogs with piercing stingers and barbed-wire claws.

The Silurian would be a nice place to visit, but unless you’re a sea scorpion, you wouldn’t want to live there.