Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Is our moon still rumbling from an ancient asteroid strike?

Violent clashes of all natures often have lasting impacts that echo long after the initial collision occurs — and our lone satellite in the sky is no exception. Once believed to be a dead rock orbiting the Earth, the moon is now displaying evidence of freshly discovered ridges on the lunar surface which are causing scientists to insist that the moon could possibly have an active tectonic system.

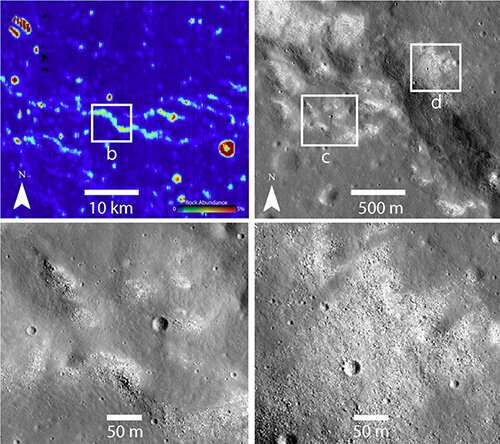

In a new study recently published in the online scientific journal Geology, researchers used data from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) to locate a variety of ridges with exposed bedrock, all suspiciously free of the powdery grey moon soil called regolith, distributed along the moon's nearside surface. These distinctive ridges, dotted with boulders of different sizes, might be evidence that some level of tectonic activity has disrupted the moon's desolate landscape.

Areas of naked ridged bedrock are not common on the moon, and the mystery of their cause can often be put to rest by rolling out the concept of ancient lava flows and volcanic activity as the main culprit. However, this new study maintains that the creation of these ridges goes far beyond basic volcanism and actually points to reverberations due to a past collision with a massive meteor, dwarf planet, or other rogue heavenly body some 4.3 billion years ago.

"The distribution that we found here begs for a different explanation," said lead study co-author Peter Schultz, a professor in Brown University's Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences in an official statement. "There's this assumption that the moon is long dead, but we keep finding that that's not the case. From this paper, it appears that the moon may still be creaking and cracking — potentially in the present day — and we can see the evidence on these ridges."

Shultz and his team, headed up by University of Bern grad student Adomas Valantinas, employed the LRO's temperature-taking Diviner instrument to discern which types of rocks and what sorts of surfaces exist in specific areas as territory blanketed in lunar regolith tends to be chillier than exposed areas of regolith-free bedrock.

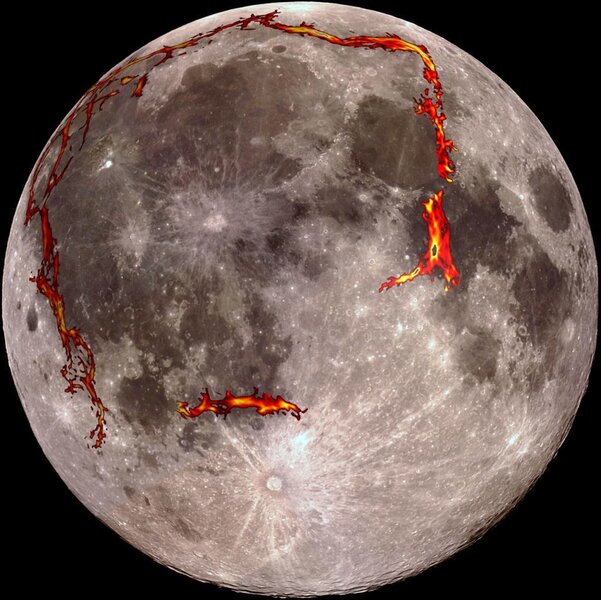

Applying these observations, the crew was able to identify 500 bare blotches of exposed bedrock along thin ridges spread across the moon's surface near the darkly-patched lunar maria. Valantinas and Schultz then traced and mapped these exposed ridges to reveal that they synched up exactly with ancient cracks in the moon's crust revealed by NASA's GRAIL mission of 2014, which concluded that magma once oozed through these splits up to the moon's surface.

"It's almost a one-to-one correlation," Schultz explained. "That makes us think that what we're seeing is an ongoing process driven by things happening in the moon's interior. This looks like the ridges responded to something that happened 4.3 billion years ago. Giant impacts have long-lasting effects. The moon has a long memory. What we're seeing on the surface today is testimony to its long memory and secrets it still holds."

This idea of the moon's Active Nearside Tectonic System (ANTS) indicates that those recent ridges located above the ancient cracks are still experiencing upheaval, causing regolith to drop into gaps which leave bedrock exposed. The theory posed is that ANTS first began billions of years ago when the moon was struck with a sizable impact that formed the 1500-mile South Pole Aitken Basin and whose enduring ripples are still being felt and reacted to today.