Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Europa's 'chaos terrains' deliver Earth-level oxygen to the ocean below

It's like a bunch of frozen snorkels helping Europan aliens to breathe.

The question of whether or not there is life elsewhere in the universe has nagged at humanity’s psyche for ages. The simple math of existence seems to suggest that there must be, but it might be too distant for us to ever see it, let alone interact with it. It’s possible, however, that there is life much closer to home, within our own solar system. If there is, there probably isn’t any better place to look for it than Jupiter’s moon, Europa.

Life as we know it requires a few basic supplies in order to get going and sustain itself. In addition to the molecular building blocks that make up life, it needs water, an energy source, and it probably needs oxygen. It’s likely that Europa has most, if not all of those things at the ready.

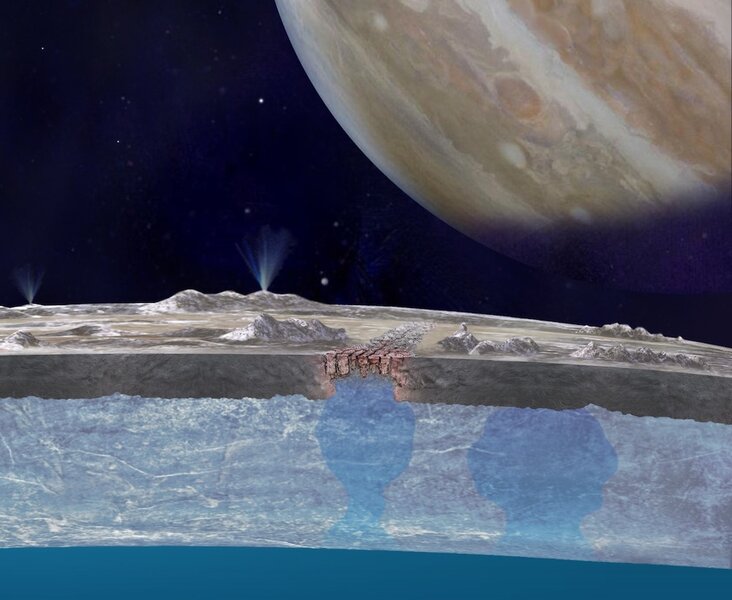

Previous research has suggested the chemical building blocks of life might be more common than we once thought, and there’s pretty solid evidence that there’s liquid water beneath Europa’s icy surface. Europa exists inside a complex gravitational ballet between Jupiter, the rest of its moons, and the Sun. The tidal forces at work very likely keep its core molten and maintain a global liquid ocean beneath the ice. Now, scientists may have identified an oxygen transport system for delivering oxygen from the surface to the waters below.

Marc Hesse is a professor in the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Texas and lead author of the paper describing the process.

“What we didn’t know was where the oxidants would come from. Then there was this tantalizing observation that the surface seems to be full of oxidants and the question now is how it could get through the ice,” Hesse told SYFY WIRE.

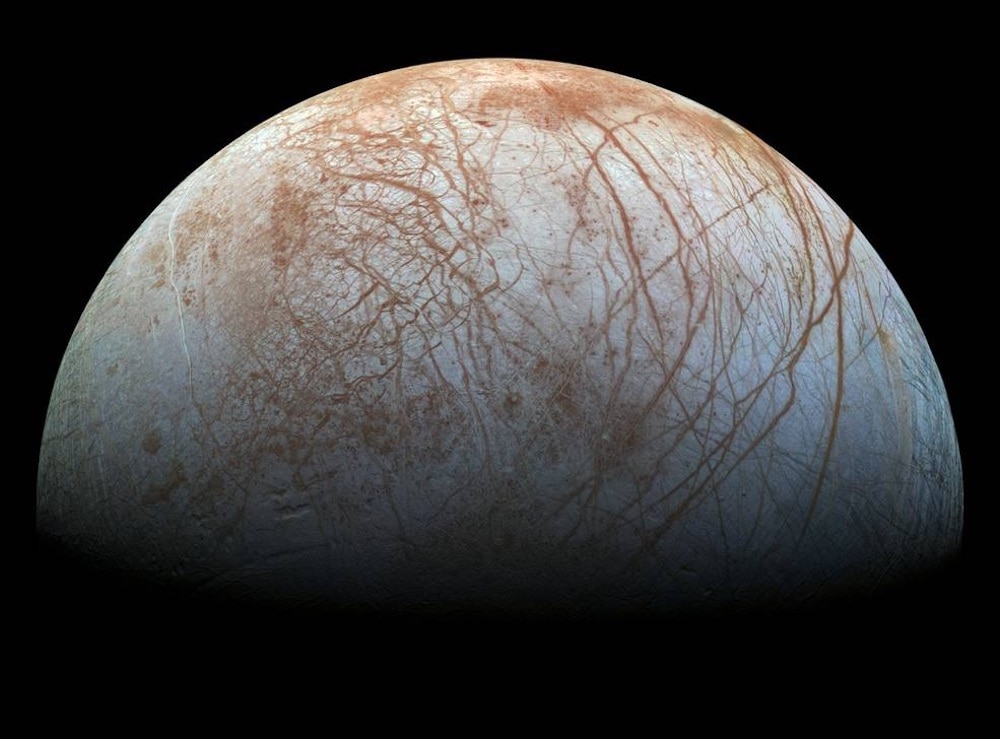

Sunlight striking the surface of the moon reacts with the ice to create oxidants, among these are O2, the oxidant we’re most familiar with here on Earth. What was less clear was how deep oxygen penetrates into the surface ice and how that oxygen could get through the moon’s thick ice and into the subsurface oceans. Europa’s ice sheet, which is estimated to be roughly 15 miles thick, serves as a considerable barrier between the surface and the ocean below.

“We think the oxidant saturation is somewhere in the range of tens of centimeters up to a few meters. It’s not saturated, but it does contain oxidants. If there is active cryovulcanism or other resurfacing processes, that would help to bury it deeper,” Hesse said.

Still, there’s a considerable difference between a few meters and a few miles, and the oxygen would need a reliable way of traveling through the ice if surface oxygen ever hoped to reach the global ocean.

The team created models to replicate the physical process believed to be present on the surface of Europa. As tidal activity or other processes cause portions of the ice to melt, a brine forms on the surface which captures oxygen in the slush. These regions are known as "chaotic terrains," and they could indicate pores in the ice, acting as temporary tunnels through the sheet. The models suggest surface brine is able to drain through those pores before they freeze again.

“The melted water is denser than ice and has a tendency to want to go down. It could be through porous flow, through fractures, or through viscous overturn. In all those cases, the result is the same. There’s brine and it’s draining, and it’s carrying the oxidants down,” Hesse said.

Just how much oxygen is being carried to the subsurface ocean depends largely on how deeply the regolith is permeated with oxidants and how common these chaotic terrains are. The estimated range is wide and varies by orders of magnitude, but within that range is a level of oxygen comparable to that found on Earth’s oceans.

NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission should gain a much clearer picture of the icy moon, answer some of these questions, and help planetary scientists to refine their environmental models. Here’s hoping the surface is good and chaotic, so that any alien life below the surface can breathe a little easier.