Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Pluto Is Sublime. It’s Also the Pits.

Astronomers are still getting data back from the New Horizons space probe from July’s Pluto flyby, and some new ones are a bit … odd.

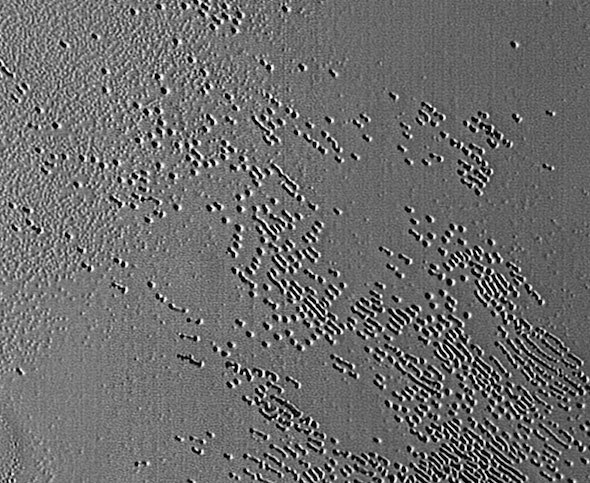

I mean, they’re all odd—Pluto is a really strange place—but this one has a new feature. The shot above shows hundreds of pits in Sputnik Planum, the “atrium and ventricle” of the famous heart-shaped region. This huge area is probably a depression on the surface filled with frozen nitrogen, which may have flowed into the lowlands like a glacier, smoothing it over. The lack of craters indicates it’s younger than the rougher highlands; though how old isn’t clear. A hundred million years, maybe more. (Note: The NASA press release has the images flipped vertically with respect to earlier photos, so I flipped them back to match the map of the area you can find below.)

The Sun is shining more or less from the left in these shots, as you can tell if you look closely at the pit walls. The bigger, circular pits look to be roughly a kilometer across, with some bigger. The smaller dimples on the left are a few hundred meters across, and some tens of meters deep.

These are likely to be sublimation pits, depressions in the surface when ice turned directly into a gas from sunlight. They probably start very small and grow over time as the Sun shines down on them.

Many of the pits are connected, forming short troughs, aligned in the same direction. That’s interesting! It’s unclear to me why that might happen. If this were Earth, I’d guess the pits would align depending on the overall direction of sunlight. For example, near the Earth’s North Pole, the Sun would shine more directly on the northern walls, so the pits would connect in a north/south line as they grew in size preferentially toward the north until they overlapped with another pit.

But Pluto is tipped way over with respect to its orbit! Over the course of its 250-year orbit, the Sun can hit these pits from literally every direction. I’d guess these features are far older than that, so there may be more going on here than simple sublimation.

This area, farther toward the center of the heart, shows wiggly patterns to the pit alignments. They get darker where they’re bunched together, which is likely a topological effect; you’re just seeing more shadows there in one spot, making those parts look darker. I have to wonder, though: Are the wiggles due to movement of the nitrogen ice? Does it still flow, achingly slowly, over huge stretches of time? And why is there a smooth stretch from the upper left to the lower right? Different material?

So many questions. I was chatting with my friend Emily Lakdawalla (who will no doubt have much more to say about these features at some point on her blog when she’s done playing with new Cassini images) about these pits, and we came to the conclusion—stop me if you’ve heard this before—that Pluto is just really weird.

She offered this bit of wisdom, which I really like and agree with: “I've concluded that flyby missions are for teaching us what questions to ask. You need orbital missions to have a hope of answering some of those questions.”

We can answer lots of questions with just the flyby data from July. But those data raise a hundred questions for each one answered … and so in the end what this may be teaching us is patience. It’ll be a long time before we get an orbiter to Pluto; even if we could build one today, it would be decades before it could reach Pluto and start sending back data.

So what you see is what you get. But, as New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern points out, a lot of the best stuff is still sitting on the probe’s hard drive. We’ll see more and more of it over the next few months, and no doubt every one will be a surprise.

Except to reinforce that Pluto is weird. That’s no longer a surprise.