Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Pregnant mummy reveals fetus that wasn't just mummified, but pickled

Bizarre things can happen with body chemistry after death.

If you’ve ever meandered through an exhibit of oddities, you’ve probably seen some freakish things preserved in jars, but this goes far beyond a pickled snake or toad with two heads.

There is no jar that holds a mummified fetus which should have been born over 2,000 years ago in Egypt. After the expectant mother died, she became its coffin when she was embalmed, since the embalmers mysteriously didn’t remove the fetus with all the internal organs. Evisceration was a defense against decomposition, but the fetus was mysteriously left there to mummify. The researchers who virtually unwrapped her through CT scans now want to know why.

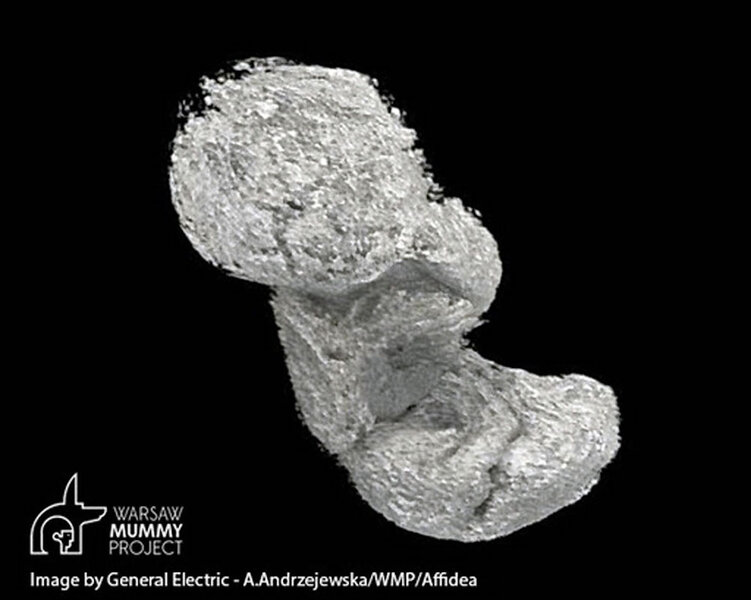

When the only known pregnant Egyptian mummy was first discovered, she was almost mistaken for a male priest. Archaeologist and anthropologist Marzena Ożarek-Szilke of the University of Warsaw and archaeologist Wojciech Ejsmond of the Polish Academy of Sciences are co-directors of the Warsaw Mummy Project and coauthored a study recently published in Journal of Archaeological Science. They examined her and were shocked to find that she was around 26 to 30 weeks pregnant. The fetus that had never been born was barely visible.

“After death, bones began to undergo a demineralization process due to the acidic environment around the body of the fetus,” Ożarek-Szilke and Ejsmond told SYFY WIRE. “Bone minerals began to dissolve in the acidic environment of blood and amniotic fluid, the pH of which changes from alkaline to acid postmortem.”

The bones of this fetus were found to be made mostly of cartilage, which had begun to ossify, or turn into bone, in some places. Ossification happens when cartilage cells grow larger and rearrange themselves so they end up in rows where they are further apart. These rows are embedded in a matrix. Deposits of calcium carbonate cause the matrix between cells to calcify, and the cartilage cells themselves are eventually trapped in the calcified matrix and degrade. Some ossification centers — where bone starts to form — were found in the fetus.

Much bone was eaten by acid. Human blood has a pH of 7 (neutral), which is the minimum for an alkaline substance. After its mother died, the pH of her amniotic fluid in her uterus plummeted, with ammonia and formic acid concentrations increasing enough to dissolve bone and preserve the fetus. When the body was then covered in drying natron salts, the fetus dried with it as if it was a part of the body (something that may have to do with why it was left there), and showed the same kind of tissue mineralization seen in other Egyptian mummies.

“The body cavity was filled with natron and the body was also covered with natron, limiting the access of air,” said Ejsmond and Ożarek-Szilke. “As a result, the fetus was left untouched by embalmers and tightly closed in the uterus during mummification in an acidic environment without oxygen.”

As natron continued to dry out the woman’s body and the fetus, the soft tissue of the fetus mineralized. Though the bones could not be easily detected through CT scans like the one above, because they were demineralized by acid, that mineralized soft tissue still made the anatomical details visible enough for the researchers to see. Fragments of the skull and preserved head tissue made it possible to measure head circumference, and some leg measurements could also be made. These gave an idea of how far along the woman was.

So why was the fetus even left there? Nobody really knows. While there is no actual evidence for the reasons it was not removed from the body, it is known that the ancient Egyptians considered naming to be extremely important. You could not enter the afterlife without a name. The woman’s name remains unknown, but maybe the only way for her to make it through with her unborn child is if it was embalmed with someone who had already been named. Miscarried fetuses like King Tutankhamun’s daughters were given identities and separately mummified.

“Due to the high-quality mummification of the mother, the fetus is very well preserved,” Ożarek-Szilke and Ejsmond said. “We must remember that we are dealing with a fetus that has undergone two different mummification processes, which is truly amazing.”