Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

In order to survive some sauropods had the tooth fairy on speed dial

You couldn't build a pillow big enough.

The prehistoric tooth fairy might have really had their work cut out for them, and not just because it’s hard to get a tutu around armored skin. Many modern animals, humans included, have a limited number of teeth which they keep for the majority of their lives. Those teeth vary in size and structure depending on a number of factors, including the sort of diet the animal consumes.

For humans, that means the tooth fairy comes for us a limited number of times during childhood then never again. For dinosaurs though, keeping up with all those dental deliveries would have been a total nightmare. Similar to modern sharks, who are just teeth all the way down, all dinosaurs replaced their teeth continually throughout their lives in a process known as polyphyodonty. But the rate at which they replaced their teeth varied by species.

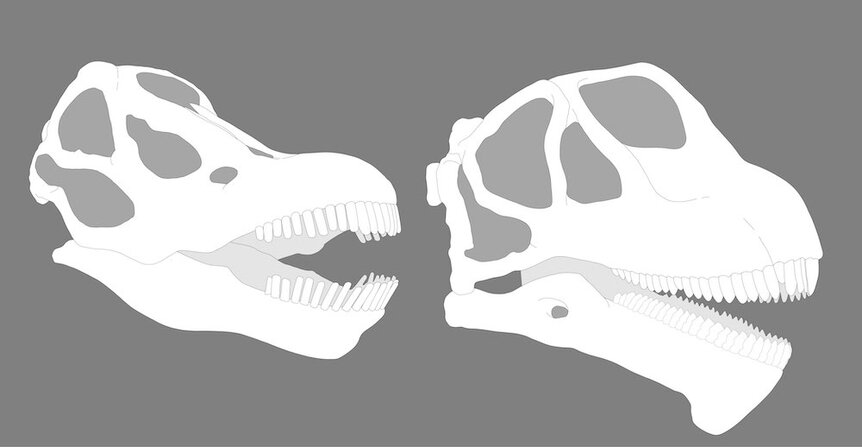

Additionally, the types of teeth an animal has almost always follows a specific trend. Carnivores have simpler teeth, wedge-shaped and sharp with minimal complexity on the surface. Herbivores have more complex teeth filled with ridges and valleys to better break down plant materials before swallowing. This rule holds true in modern animals and has little relationship with whether or not teeth are replaced or at what frequency. Sauropods, however, are dental rebels, breaking with tradition. Despite their plant-based diets, they have shockingly simple teeth which, by some measures, would look more at home in the mouth of a predator. What gives?

A recent paper by Keegan M. Melstrom from the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, and colleagues, outlines the way sauropods buck the tooth trend, trading complexity for rapid replacement. Their findings were published in the journal BMC Ecology and Evolution. The study builds on previous research which had identified the replacement rates of teeth across a number of different species by examining their internal structures as well as the layout of the jaw.

“Basically, you take the teeth, cut them, and count the lines,” Melstrom told SYFY WIRE. “Similar to how a tree lays down a ring every single year, teeth do the same thing for dinosaurs. Scientists also used CT scans to count the teeth in the jaw and estimate replacement rates.”

Sauropods have variable replacement rates. Some species, like Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus replaced their teeth every 80 to 90 days, while others replaced all of their teeth much more frequently, as often as every two weeks.

“In Nigersaurus, each tooth would have been dropped every 14 days,” Melstrom said. “They’d probably be dropping a couple of teeth a day. For each erupted tooth there were seven teeth being grown at the same time.”

This variability existed even among species who were living together at the same time and in the same general area. And looking at the data, a pattern began to emerge. The tooth replacement rates of sauropods correlated nicely with complexity. Those animals with more complex teeth held onto them longer, while simpler teeth were basically dropping out of the jaw almost as soon as they emerged. These exceedingly simple teeth in herbivores broke the trend seen in almost every other animal, living and dead, across the world.

“Today, almost every animal that eats plants has complicated teeth. Iguanas that replace their teeth constantly have complicated teeth; horses have complicated teeth. So, the fact that sauropods have done something different was surprising,” Melstrom said.

The answer might come down to their diets. In order for large animals to live together in the same space they need to minimize competition. There’s only so much food to go around. One way to do this is to partition resources through food preferences.

Melstrom looked at the plants which were prevalent at the same time and location as these sauropods and found something startling. There was evidence some sauropods were eating equisetum (horsetail) which still exists in the world today. The plant has high energy content as compared to other plants, but is also rich in silica on its surface, making it hard to chew. These abrasive plants would have done damage to the teeth of anything eating them regularly.

Modern animals, like rodents, can get around these sorts of challenges by having teeth which never stop growing. Their diets wear them down, but they just grow back again. Sauropods seemingly solved this problem in a different way. Having simple teeth which were rapidly replaced could have allowed them to eat plants which would have been too damaging for teeth which stuck around longer.

“It’s tough for these animals to live side by side and eat the same things because then you’re competing, but if you’re eating different things then you don’t have to compete to the same degree,” Melstrom said. “That’s likely being manifested in things like tooth shape, complexity, and replacement rate. It’s all pointing to an environment where these animals who are huge are trying not to compete while living together.”

Simpler teeth might have had the added benefit of making the head lighter, reducing the energy requirements of holding it at the end of a long neck.

“There could be other explanations,” Melstrom said. “But I think it’s that constraint of making sure your head is as light as possible that caused them to innovate and have higher replacement rates and lower complexity.”

It goes to show that evolution doesn’t play by hard and fast rules. When there are multiple strategies for solving a particular problem, sometimes it’s a roll of the dice, even if those dice are loaded. Certainly, the overwhelming evidence suggests that evolution favors one solution over another in this case. Almost every plant-eating animal has complex teeth regardless of replacement rate. Sauropods are an interesting exception to this rule and while this sort of dental strategy is rare, it may not be totally unique.

“There is potential that it happened a second time. Independently in this other group of sauropods called titanosaurs, they also evolved high teeth replacement rates and their teeth start to look simple. This strategy was successful enough that given the opportunity life went that way again,” Melstrom said.

Teeth falling out might be a common nightmare scenario for many of us, but it worked for sauropods. There’s no such thing as mounting dental bills when you have replacement teeth on constant delivery.