Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Closest approach: Scientists found a black hole less than 1,600 lightyears away

That's about as close as we like.

Before Stephen Hawking was synonymous with genius, he was an astrophysics student at the University of Cambridge. There, he began thinking about black holes, a path of inquiry which would eventually lead to a career as perhaps the greatest mind in a generation. It also led to The Theory of Everything, a dramatic adaptation of Hawking’s life, released in 2014. Hawking’s work, along with colleagues all over the world, has revealed a cosmos filled with endlessly hungry gravity wells whose numbers nearly rival the stars themselves.

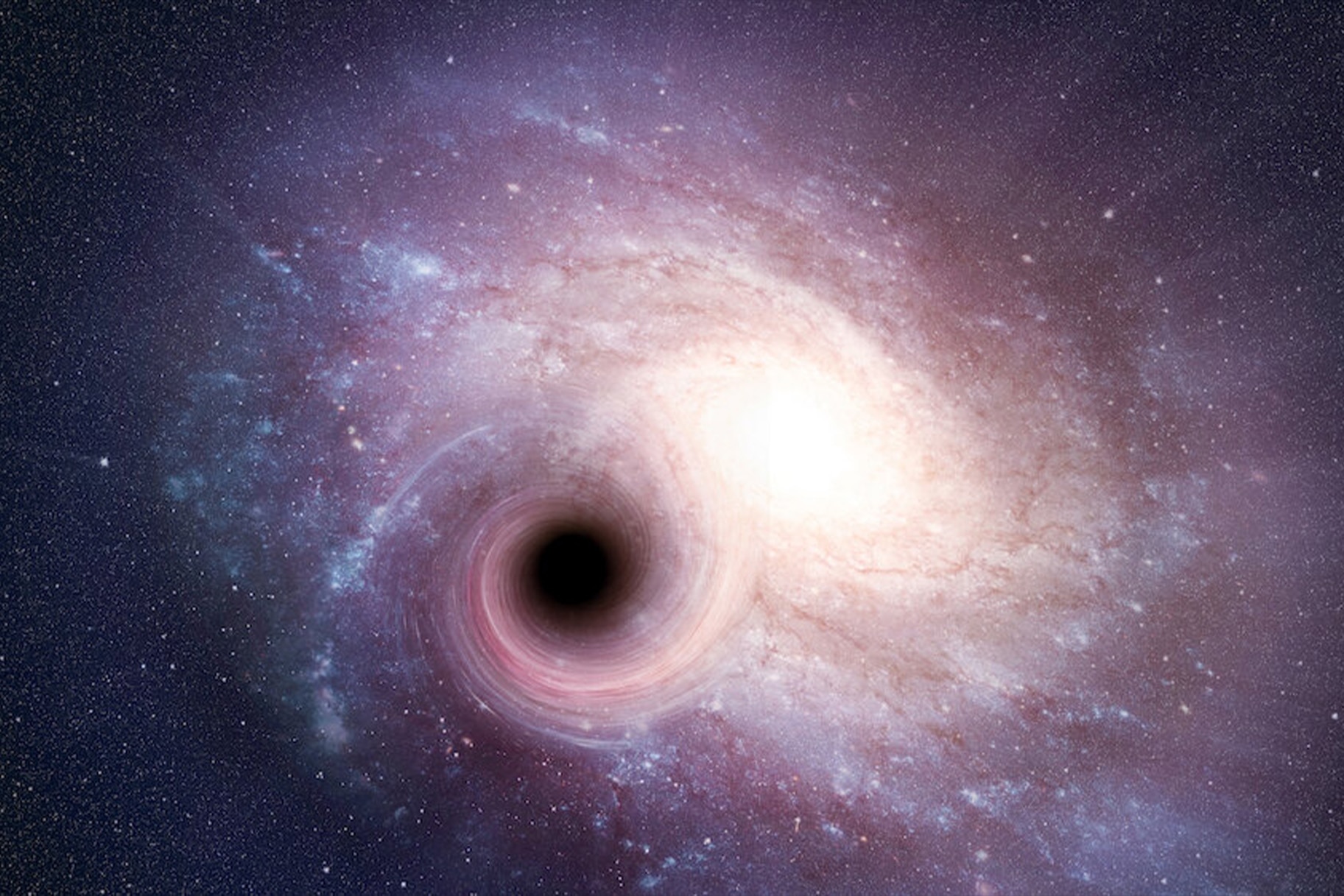

It’s believed there are supermassive black holes at the heart of every galaxy, an incredible point of intense gravity around which the galaxy spins. In recent years we have succeeded at imaging some of those black holes, confirming they are right where we expected them to be. There is, however, another kind of black hole which is more difficult to find. Scientists estimate there are 100 million stellar mass black holes, with masses between five and 100 times that of our Sun, populating the Milky Way alone, but they are incredibly difficult to find.

Most of the stellar mass black holes we have detected so far are in the process of consuming nearby companion stars. The light from these destructive close proximity relationships lights up the sky with X-ray light, making them easier for our telescopes to see. Black holes not in the process of filling their endless maws are effectively invisible, except for the ways their gravitational influence distorts the space around them. Recently, scientists pinpointed the location of one of these dormant stellar mass black holes and it’s closer than any black hole we’ve ever found before.

An international team of astronomers used combined data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft and ground based telescope observations to closely measure the gravity around a star roughly 1,600 lightyears away and found a black hole hiding nearby. Their findings were published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Researchers started their search by scouring the data collected by Gaia. During its mission, it has mapped the positions, speeds, and trajectories of roughly 2 billion stars in our own galaxy. While looking at the Gaia data, researchers noticed small irregularities in the movements of a star 1,560 lightyears away in the constellation Ophiuchus, which suggested the presence of something massive but invisible nearby. They then studied the star more closely using ground based telescopes in Hawaii and Chile.

The combination of data confirmed the presence of an unseen object about 10 times the mass of the Sun near the target star. In fact, the distance between the star and the black hole is about the same as the distance between the Earth and the Sun. “Take the Solar System, put a black hole where the Sun is, and the Sun where the Earth is, and you get this system,” said Kareem El-Badry, the paper’s lead author, in a statement. This discovery is the first confirmed observation of a dormant stellar mass black hole which would make it notable all on its own, but its position less than 1,600 lightyears away also places it about three times closer to Earth than the previous proximity record holder. That’s still plenty far away for us not to worry about it, at least in the foreseeable future.

It’s likely the black hole, dubbed Gaia BH1, was formed by the death of a star 20 times the mass of the Sun or more. These kinds of stars are short lived, their fuel burns bright, hot, and fast, and they die young, usually after only a few million years. For comparison, our Sun is believed to be about 5 billion years old and it’s only middle aged.

Their short stellar lives are a tradeoff for a second life as a black hole, and that life is much longer. Scientists believe that the end stages of the universe will begin with the deaths of the black holes. That death is in progress right now, but it will take an incredibly long time. Slowly but surely, black holes radiate energy away and lose mass. That radiation, appropriately enough, is called Hawking radiation.

In the universe’s distant future, after the stars have gone cold and the cosmos has fallen into true darkness, the black holes will begin to die. With nothing left to consume, no way to refill their larders, their mass will evaporate away until they fizzle out of existence. Even for a black hole like Gaia BH1, which is small compared to the supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies, and which isn’t bothering to gobble up the food source nearby, that evaporation will take longer than the universe has existed. For all intents and purposes, we’re stuck with black holes, and it’s nice to know we’re getting better at finding them.