Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Seeing through the Meathook Galaxy

Just about 70 million light years away — a stone’s throw, in a cosmic sense — lies the galaxy NGC 2442. It’s a lovely example of a spiral galaxy, with two wide flung arms and lots of stars merrily being born in them.

But it’s also weird. I’ll get to that, because it’s not readily apparent in the first image I want to show you, but it will be as you read on.

The image below was created by astrophotographers Robert Gendler and Robert Colombari. They merged images taken by the space-based Hubble Space Telescope and the European Southern Observatory’s ground-based MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at La Silla, Chile. What they made is magnificent:

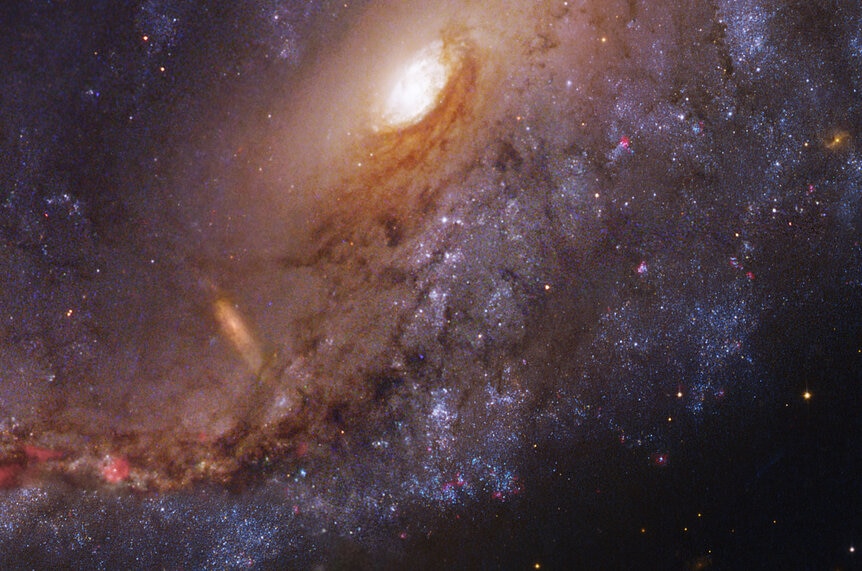

Oh, wow. Look at the detail! You can see the myriad reddish gas clouds forming stars strewn along the length of that one arm, and dark dust lanes obscuring the stars behind them. That bright blue patch is also a site of star birth; the massive, luminous stars born there are blue, and completely outshine the lower mass redder stars, giving that region its hue.

The central region of the galaxy is interesting. It’s not quite spherical, but neither is it elongated into a true bar, a rectangular-shaped volume of stars seen in many galaxies (including our own). I looked it up and, sure enough, NGC 2442 is classified as an SAB galaxy: a spiral that is intermediate between having a bar and not having one.

One thing that is hard to tell from this shot is why NGC 2442 was given its nickname: the Meathook Galaxy. Perhaps this wider-angle view will make that clear:

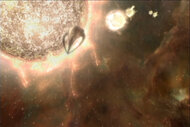

Aha! That one spiral arm is oddly shaped, curved wickedly. This image doesn’t have the resolution of the Hubble one, so you can’t see the details as well, but that actually helps a bit in seeing large-scale features, like the reddish-pink gas clouds all along that long arm.

Why are they shaped this way? Most likely, NGC 2442 suffered a collision with another galaxy in the past —perhaps 200 million or so years ago — and the gravitational interaction between them drew out the arms like taffy. This is very common in galactic collisions, actually.

Interestingly, you can usually see the culprit intruder galaxy somewhere nearby, and that might be the case here. The fuzzy galaxy to the lower right is called AM 0738-692. Spectra taken of both galaxies show they lie at about the same distance from us, making it very likely the smoking gun. Not only that, but AM 0738 is also distorted-looking, with arms that look very much as if they’ve been pulled out by a recent encounter. Studies of both galaxies indicate that they may fall back together and merge in the next three billion years or so. Mark your calendars.

It’s funny. In galactic collisions, huge gas clouds will slam into each other, collapse, and form stars (that is likely why NGC 2442 has such fecundity, in fact). But stars are very small compared to the distances between them, so the odds of a stellar head-on train wreck are actually pretty small.

That’s a weird thought, but take another look at that Hubble image of NGC 2442. Just below and to the left of the nucleus is another galaxy, a nearly edge-on reddish spiral. You might think that galaxy lies in the foreground, or else we wouldn’t see it. But that’s not the case: It’s clearly in the background, behind NGC 2442, probably much farther away! The big clue is that dark streak going across it to the lower right. You can see that this is a dust streamer in NGC 2442, itself, because it continues on well past the smaller galaxy’s edges. Also, the small galaxy may look red, because we’re seeing it through the dust of NGC 2442; these small grains of metals, carbon, and rocky material tend to scatter away blue light, making objects behind them appear red. It’s similar to why hazy sunsets look red.

But that tells you just how ethereal galaxies are! As mighty — and as solid — as they appear, they are actually mostly empty space, and even close to their cores, they’re translucent. It’s quite common to see background galaxies right through closer ones. That’s also consistent with the stars being so far apart inside them.

I love seeing images of galaxies like this. There’s so much to see! Even an initial inspection can reveal so much, but then when you dig deeper, you find out that there’s a lot more going on than you might initially think. It’s one of the reasons this sort of science is fun.