Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Are those famous T. rex skeletons...really T. rex? Some fossils thought to be other species

Because everyone wants to be the undisputed star of Jurassic Park (sorry Jeff Goldblum).

If there was ever a dinosaur with celebrity status, it has to be Tyrannosaurus rex.

The beast that catapulted to fame in Jurassic Park is also a roadside attraction, a theme park ride jumpscare, and the namesake of a rock band. The inflatable costume version of it has been terrorizing comic cons for years (it isn’t a con without at least five). Famous skeletons like Stan, Wankel, Sue ,and Scotty have been eating up attention at museums, flashing their teeth to millions of wondering eyes. You know you’ve got star power when there’s a T. rex in your exhibit.

But wait. What if some of those iconic skeletons are not exactly T. rex? Make no mistake, they are tyrannosaurs, but paleontologist Greg Paul thinks there could be something else among them. T. rex has become something of a stereotype. Paul, who led a study soon to be published in Evolutionary Biology, has found that there are subtle variations in supposed T. rex fossils that might indicate other, still tyrannical species of tyrannosaur that were previously unknown.

“Because species are very close relatives, there are few differences between them, and they can often interbreed, which increases the similarities,” Paul told SYFY WIRE.

There have been mistaken identities the other way around. What was thought to be the smaller Nanotyrannus actually turned out to be a juvenile T. rex. Inversely, when looking at adult tyrannosaur specimens up close, Paul noticed that some of them had a more robust build while others, like the notorious Stan which went for almost $32 million at auction in 2020, had more slender bones. The “robusts” and “graciles” presented a problem. Did this mean T. rex was sexually dimorphic — that the females were physically different from the males? Maybe not.

With no surviving DNA to go off of, and no remnants of skin or feathers that would suggest differences in coloration between sexes or species, Paul turned to the rock formations from which the fossils were originally unearthed. Finding that robusts and graciles came from the same level of the formation could have suggested they were males and females of the same species. It was either that, or the different species coexisted. If robusts and graciles had been fossilized at different levels, that would mean an evolutionary giveaway.

“In one way or another the two species had evolved separately,” said Paul. “All species are transitional from one to another, unless a species goes extinct before a new one has evolved from it.”

There were apparently gradual changes in these tyrannosaurs over time, especially in the femur, or thighbone, and teeth. Earlier femur specimens showed more bulk. There was more variation in the femora of tyrannosaurs thought to be T. rex than there was in any other tyrannosaurid. Also, earlier versions of this creature’s lower jaw had two front teeth, which were small incisors, while specimens from later on had only one small incisor at the front (“small” is relative here when you’re talking about a mouth full of teeth up to six inches long). Suspicious.

The holotype of T. rex is a robust. That might be one reason why anything close enough was assumed to also be T. rex by default. More evidence that deepened the mystery surfaced as Paul realized that robusts didn’t just vanish from the fossil record when graciles began to appear. It could only mean that some of these robusts, for whatever reason, were evolving into more slender versions of a dinosaur that is thought to have been so bulky it had trouble getting around. The graciles became more common later on, and even robusts were less…robust.

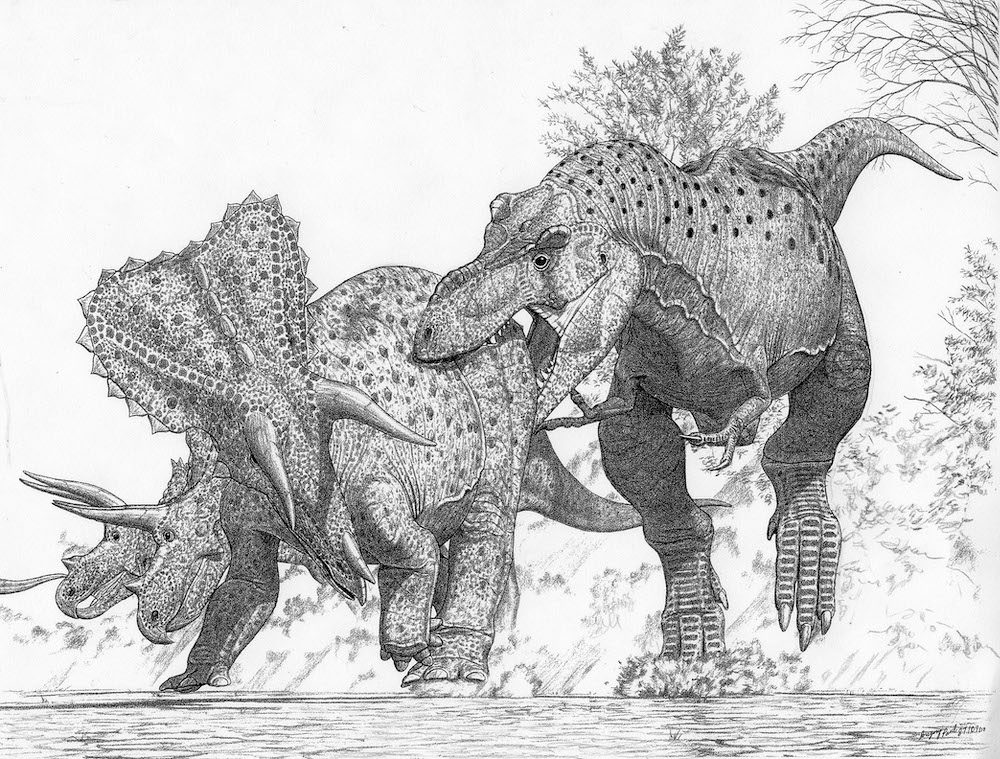

“It is possible that the graciles evolved to hunt unarmed edmontosaur hadrosaurs, while the robusts focused on the massive and heavily armed Triceratops,” said Paul. “However, the edmontosaurs were much less common, so why that would have happened is not clear.”

Whether the graciles were juveniles is out of the question. Tyrannosaur juveniles are nothing like adults, with a much lighter build and longer legs that were more suited to chasing after smaller, swifter prey. Their skulls were also long and low compared to the bone-crushing adult skulls. After a thorough investigation, Paul and his research team were able to tell two gracile tyrannosaur morphotypes apart from T. rex. These possible, though not yet official, species are T. Regina, the tyrant lizard queen as opposed to the lizard king, and T. imperator, the lizard emperor.

Of course, nothing has a bite in the media like the name T. rex. Paul's findings have some stubborn opponents. He speculates that museums which have what they think is a T. rex skeleton on display may be afraid of losing visitors if they own up to the species being mistaken. The misrepresented Stan (now in an Abu Dhabi museum) is most likely a T. Regina.

In the meantime, Paul would be thrilled if a rock band called Tyrannosaurs imperator could exist. It just sounds fierce.