Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Supermassive black hole has been caught stuffing its face with space dust

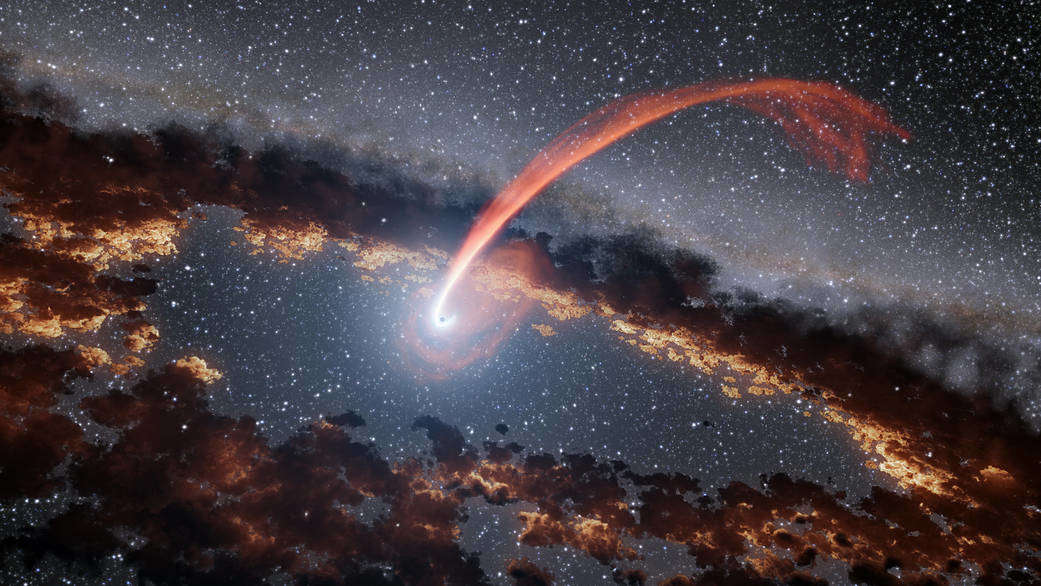

Whatever passes too close to a black hole is doomed. Entire stars can get shredded if they don’t keep their distance, and so can anything else pulled in by its monstrous gravity.

However scary the constantly gaping maw of a black hole sounds, no one has actually been able to image it devouring the cosmic dust and gas it usually feeds on—until now. Even the astounding image of the M87 black hole didn’t catch that. This is the first time a team of scientists, led by astrophysicist Almundena Prieto, were able to get a direct look at a supermassive black hole in the center of a galaxy as it was voraciously eating stardust.

Prieto, who led a study recently published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and her colleagues at Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), were able to use images from Hubble, the Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) to create an unprecedented visualization. The combination of images from these telescopes shows the nuclear black hole of galaxy NGC 1566 glutting itself with long, thin filaments of dust swirling towards its mouth before they vanish forever.

“Black holes are in a rather quiescent state for most of their time, and they do not need much food either, so such an event is rare,” Prieto told SYFY WIRE. “Capturing these events also requires extremely powerful telescopes that can see through the surroundings of a black hole to unveil a bunch of long, narrow filaments in such a detail.”

Dust, gas, photons and other particles caught by the gravity of a black hole end up in its accretion disc, moving ever closer until they finally reach the event horizon, or the point of no return. They will end up as food for the black hole once they overstep it (and that much gravity makes it impossible to turn back). These particles then fall further and further until they are lost in a place with so much density and gravitational force, even light cannot escape. Previous telescopes were just not powerful enough to capture the series of images needed to create a composite of this phenomenon.

What made a difference this time was the ability to image two critical things that were combined for the visualization. The telescopes used could see with a high angular resolution and also visualize their surroundings as a panorama. Angular resolution is the power of a telescope to see the smallest angle at which it can see objects separately. The diameter of its lens or mirror and the wavelength in which it is seeing factor into this, with the wavelength divided by the diameter giving its resolving strength.

Together, Hubble, the VLT and ALMA were able to produce images that allowed Prieto and her research team to follow the dust filaments as they began their final death spiral.

“By combining both spatial resolution and light from different spectral ranges, we can penetrate into the center of a galaxy to uncover its structure and see what is going on there,” she said.

This research was part of the IAC’s PARSEC project, which is intended to figure out how supermassive black holes wake up after such long periods of quiescence, begin to accrete massive amounts of material and feed again.

Galaxies studied for the PARSEC project are observed with extreme angular resolution. They were also seen at different wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum, such as infrared and radio, which both have waves too long for the human eye to see. Infrared light can see through galactic dust because its longer waves can sneak between particles visible light cannot.

“These images are snapshots in time,” Prieto said. “Because these phenomena take many millions of years, we could not capture what was going on before or after. In this galaxy, we captured the arrival of the filaments at the time they started to spiral towards the center.”

Black holes actively eating could also be the reason why the centers of galaxies mysteriously darken sometimes—there is too much dust crowing around the nuclear supermassive black hole.

Prieto and her colleagues will keep searching to find out when and how these beasts awake and reactivate.