Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Earliest predator ever discovered is a tentacled nightmare named for David Attenborough

Early animals were basically hitting random in the character creation menu.

Generally speaking, if you find yourself at the business end of a tentacled beast, you’re going to have a bad time. That was certainly the case for the residents of Perfection, Nevada in the movie Tremors. There, great underground monsters called Graboids hunted anything that moved, latching onto prey with multiple tentacle-like tongues.

Tentacled monsters aren’t just for the big screen, however, they might also have been the earliest predators to ever hunt other species in the ancient oceans. A recently discovered fossil reveals the most ancient animal with living descendants ever discovered. Frances Dunn from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, in collaboration with the British Geological Survey (BGS), described the animal in a recent paper published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

The animal, dubbed Auroralumina attenboroughii lived during the Ediacaran Period and has spent the last half a billion years or so hiding out in Charnwood Forest in the northwestern part of Leicestershire, England. That’s where famed biologist and science communicator David Attenborough spent his childhood. The fossil was named after him in honor of his connection to the area and his contributions to popularizing Ediacaran paleontology.

In 2007, the British Geological Survey went to Charnwood Forest and made a massive silicone rubber mold of the entire fossil surface. Those molds were then housed at the BGS where scientists could study them. That’s where Dunn got her first look at Auroralumina attenboroughii.

“I was shown the fossil by one of the authors on the paper, Phil Wilby, and it was instantaneous, we both new this was something really, really special,” Dunn told SYFY WIRE.

At first glance, it’s difficult to know precisely what you’re looking at when viewing images of Auroralumina. That’s because fossils in the area were preserved in a relatively uncommon way. When we think of fossils, we often think of dinosaurs with great bones beautifully mineralized, but that’s not what happened with the creatures who lived during the Ediacaran.

“These beasts lived at the bottom of the seafloor and there was an underwater volcano which erupted and smothered everything, kind of like an ancient underwater Pompeii. What you’re looking at are the impressions the fossil made when it fell to the seafloor,” Dunn said.

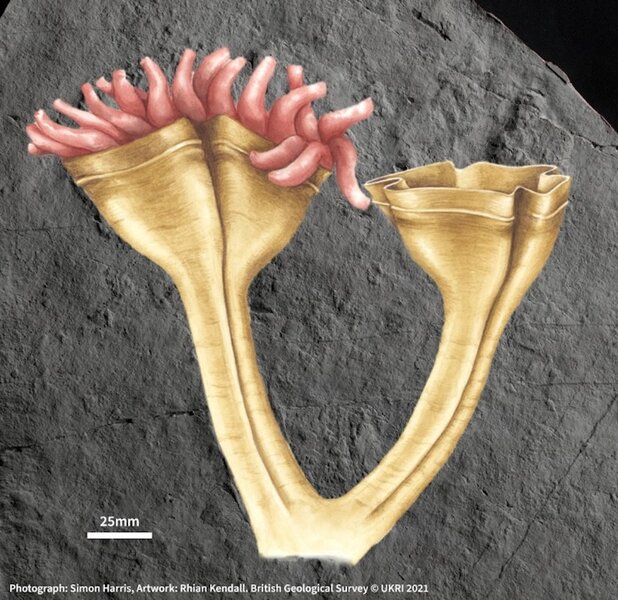

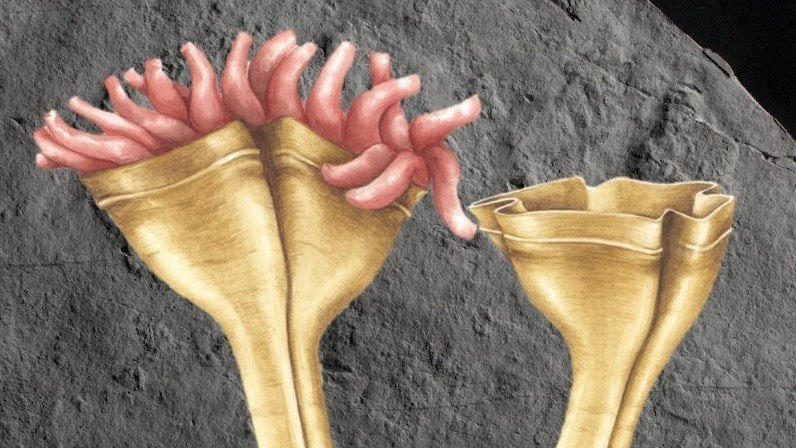

Because the animals of the time were largely soft-bodied, they didn’t have solid structures to preserve. Instead, we get the relief impressions they left behind when they were covered over with silt or underwater volcanic ash. That means that all we have are shallow outlines and subtle topographic differences. Even still, paleontologists can glean a lot of information from those outlines. By comparing changes in how different parts of the animal were preserved, and how those parts differ from other fossils in the area, researchers were able to paint a picture of Auroralumina half a billion years in the past.

“The fossils in Charnwood Forest are very low relief, they tend to be a millimeter or two, tops. That’s not the case with Aurora, it has the highest relief of any fossil on the surface. There’s a ridge in the fossil which would correspond to an invagination in the actual living animal and that’s a centimeter or more, so the scale of the difference in relief is quite large. From that, we inferred that part of the organism was of a more rigid material than the other fossils on the surface, which we know are totally soft bodied. So, we can interpret it as an exoskeleton. Whereas the tentacular crown is preserved in more or less the same way, so we can say they were soft bodied,” Dunn said.

Moreover, Auroralumina might have been a massive predator not just when compared to its contemporaries, but also when compared to its living descendants. The fossil itself spans about 20 centimeters, which might not seem all that impressive until you realize it was in its polyp stage. Auroralumina is the oldest-known member of Medusazoa, the same group to which modern jellyfish belong.

When modern jellies are in their polyp stage, they are very small. When researchers compared Auroralumina to existing jellyfish, they found that in some cases it was as much as an order of magnitude larger. Because we only have the one specimen to investigate, it’s currently unclear whether Auroralumina spent its entire life as a polyp or if it was capable of growing into a secondary medusa stage. If it could, however, it’s possible it would have been frighteningly huge.

While Auroralumina is still being studied, it’s likely that some questions about it will only be answered if and when we find additional examples and that might be particularly challenging. When looking at the other fossils in the area, paleontologists have found that they are all oriented in the same direction. That suggests they were felled together and remain in their living positions. Auroralumina, however, is oriented differently and is missing its base. One interpretation of its condition is that it was washed in from elsewhere. If that’s the case, it might make finding other examples difficult.

Still, there is reason to celebrate. The discovery of Auroralumina pushes the line between living and extinct animals further back in time and helps to bridge the gap between the sorts of anatomical features we’re familiar with today and the comparatively bizarre creatures that lived during the Ediacaran.

There’s something comforting, if a little horrifying, in the knowledge that creatures living in the oceans half a billion years ago were subject to some of the same types of monsters we live with today.