Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

TESS saw the comet 47/P Wirtanen undergo an outburst after a debris impact

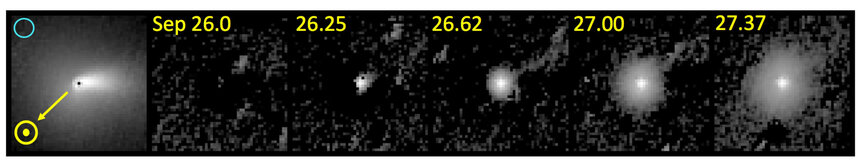

On 26 September, 2018, the comet 46P/Wirtanen underwent an outburst, brightening by a factor of 60% over the course of just a few hours… and TESS saw the whole thing.

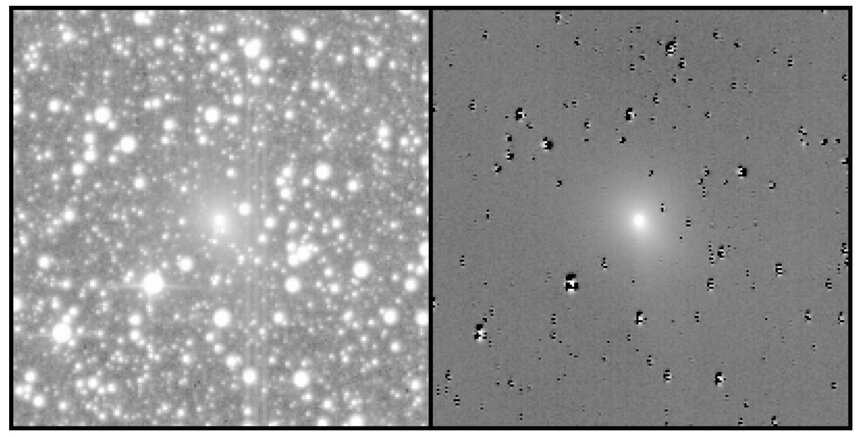

TESS — the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite — is a space-based observatory that observes huge chunks of the sky for weeks at a time, measuring the brightness of everything in its field of view with exceptional accuracy. Its primary mission is to look for changes in brightness from stars when exoplanets transit them, causing a tiny drop in their light. But it looks over such a large area of sky it sees all manners of things, including comets.

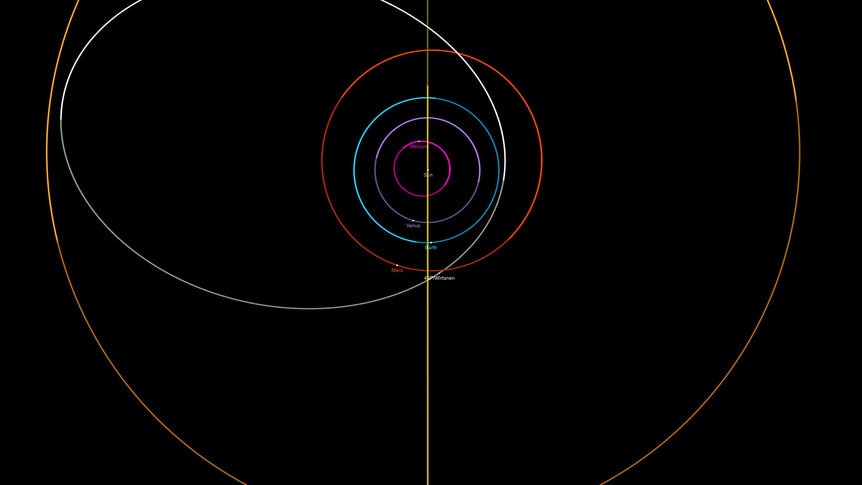

46/P Wirtanen is a comet that orbits the Sun on an ellipse that takes it from just outside Earth's orbit to just inside Jupiter's every 5.4 years. It passed Earth in December 2018 by less than 12 million kilometers and was intensely studied as it did.

By happenstance, it was in TESS's field of view from 20 September to 17 October, 2018. During that period it went from about 250 to 200 million kilometers from the Sun, and closed its distance to Earth from roughly 90 to 50 million kilometers. Happily, the outburst was during that window of time.

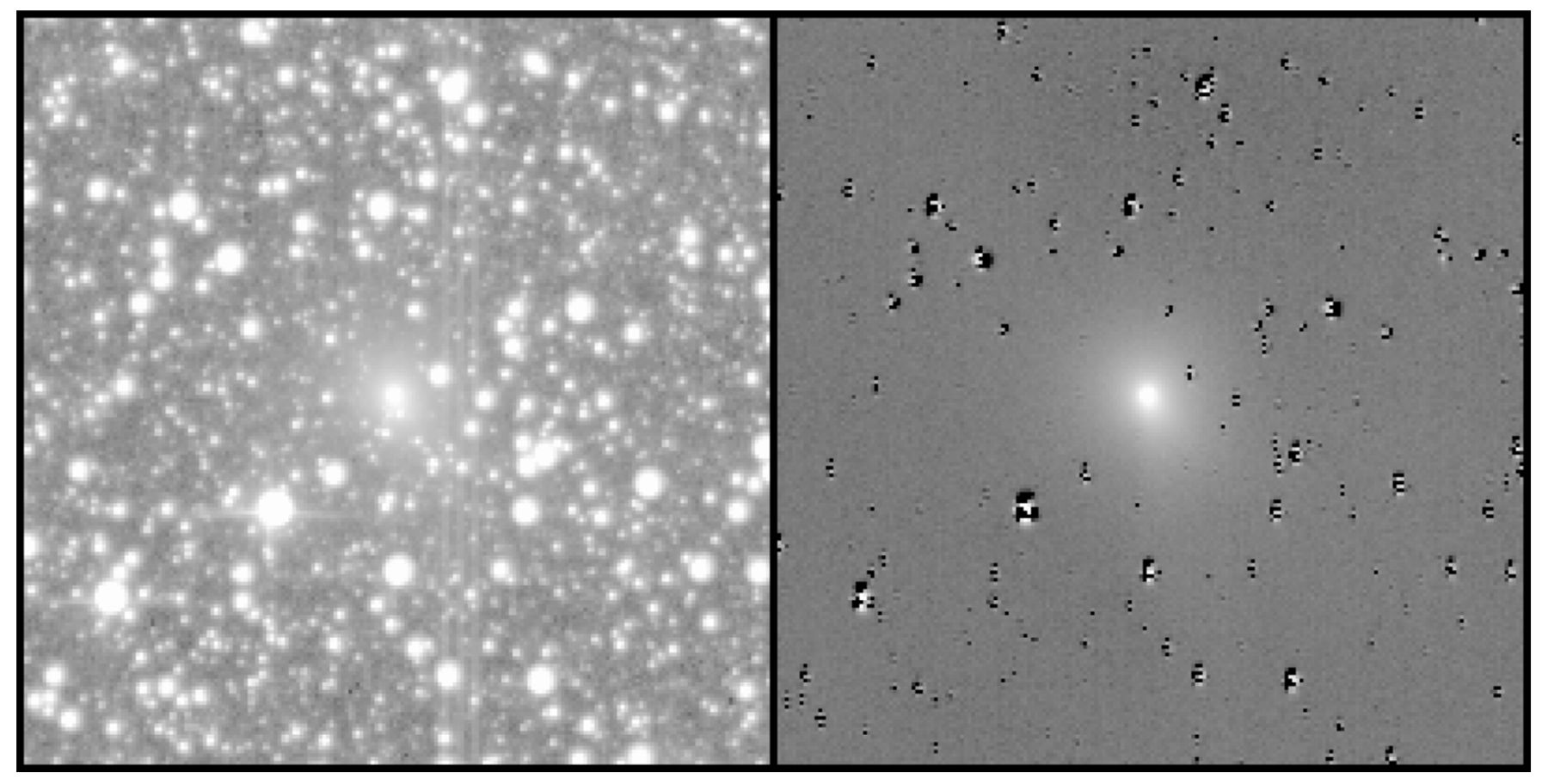

On 26 September, 46/P increased in brightness rapidly for about an hour, then continued that increase though at a slower rate for another 8 hours. At that point it started to fade, slowly decreasing in brightness for 15–20 days. We've seen comets do this before, but this is the first time an entire naturally caused outburst was seen from the very start to the point where the fading tapered off.

This happens sometimes in comets when pockets of ice on or just under their surface warm as the comet approaches the Sun, and suddenly turns into gas. The material expelled by this venting catches the sunlight and the comet, as seen from Earth, gets rapidly brighter. This was seen, for example, in the comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2015 by the orbiting spacecraft Rosetta. Even the region of the comet suddenly outgassing was spotted.

This doesn’t really match what happened with 46/P Wirtanen though. It's been seen to outburst just three times in the past, and always at different distances from the Sun. That makes it unlikely to have come from a single spot on its surface every time.

So did it come from different spots each time? Well, in this event they estimate that somewhere between 100 to 100 thousand tons of material was ejected into space in a very short time. That's not characteristic for a venting of ice. It sounds a lot more like an impact.

Comets are moving rapidly through space, and small bits of material shed previously by comets and asteroids are out there as well. If a comet slams into one of those it can excavate a crater, blasting a lot of material into space. This is likely what happened with comet 17/P Holmes, when it increased in brightness by a factor of a million as it moved away from the Sun in its orbit. It was past Mars when it happened, so unlikely to be a vent outgassing. It's far more likely it hit something which blew a huge amount of material into space around it (I'll note I saw Holmes a few days after this happened, and you could see it was a circle and not a dot by eye, even though it was tens of millions of kilometers from Earth at the time; it was one of the most amazing things I have ever seen for myself in the sky).

If this outburst TESS saw from 47/P was an impact, it would've carved a crater a few tens of meters across in the surface. The ice would've vaporized rapidly, and in fact the TESS observations show the leading edge of the expanding material moving away at 800 meters per second (nearly 3,000 kilometers per hour!). This gas was most likely CN (cyanide) which is common in comets and matches the wavelength (color) of the TESS observations. After that, dust (tiny grains of rocky material) expanded away much more slowly, ~10 meters per second.

This probably explains the two-phase brightening. The initial impact plus gas caused the brightness to increase rapidly. This faded as it expanded, but the more slowly expanding dust cloud around the comet grew in brightness as it got bigger, until it too thinned out and didn't reflect sunlight as efficiently. It then faded over the next few weeks.

This is pretty amazing. While an outburst has been seen once from start to finish before, it was artificial: When the Deep Impact probe smacked the comet Tempel I with a big block of copper in 2005 to create a crater and see what materials were under the surface (as well as to test the engineering needed to impact a comet should one be found that might impact Earth, so that we can push it out of the way). So this is the first time a natural one has been seen this way.

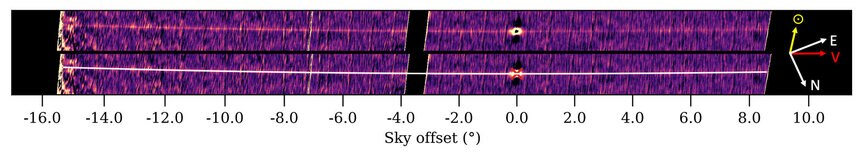

Incidentally, the TESS observations also revealed a very long trail of dust left behind by the comet along its orbit; this material is something like 100,000 km wide and a staggering 30 million km long… at least. It extended outside TESS’s field of view, so it could be substantially longer! This has never been seen before, and is another piece of information astronomers can use to understand how comets behave.

Astronomers expect several dozen comets will be viewable by TESS by the end of the nominal mission. They will be able to observe them and determine things like their rotation rates (and see if they change over time), brightening or fading over time, and more. We were lucky to get an outburst from 47/P so perfectly timed, but TESS isn't done yet. There are still many months of observations left, and no doubt NASA will extend the missions, since it's been very successful so far.

It's a big sky, with a lot going on in it, both locally and interstellarly. I'm glad we have eyes on it, especially ones as keen as those of TESS.