Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The asteroid Ryugu is a weird, fragile thing

Some asteroids, it turns out, are fragile things.

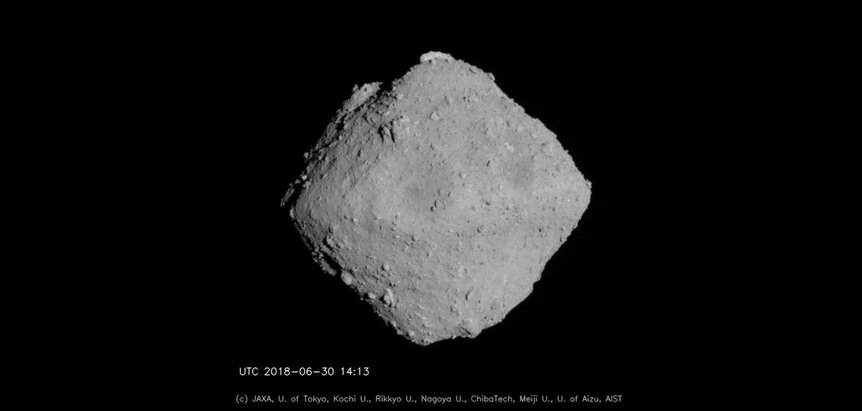

Ryugu is a tiny one, as asteroids go, just barely over a kilometer across its equator (1004 ±2 meters). It's not round, but neither is it irregular; it's shaped like a diamond, or more accurately like two squat cones attached at their bases. That's not a coincidence! It has such low gravity — I'd weigh about 1/30th of an ounce on its surface — that it doesn’t hold on to its rocks very tightly. It spins once every 7.63262 hours (yes, it's known that accurately!), so there's a slight centrifugal force outwards at the equator. That's "downhill," so rocks tend to slide down in that direction, building it up and creating the asteroid's odd-looking overall shape.

On June 27, 2018, the Japanese space probe Hayabusa2 took up residence near Ryugu, and began a campaign of not just observing it, but invading it. It dropped three landers to the surface. Two were mostly technology testers to see how to move around on the surface of an asteroid where gravity is whisper-light. The other, MASCOT (Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout), had scientific equipment on it to get extremely up-close and personal data on the surface.

The results of this geology experiment have just been published, and they reveal that Ryugu is, well, really weird.

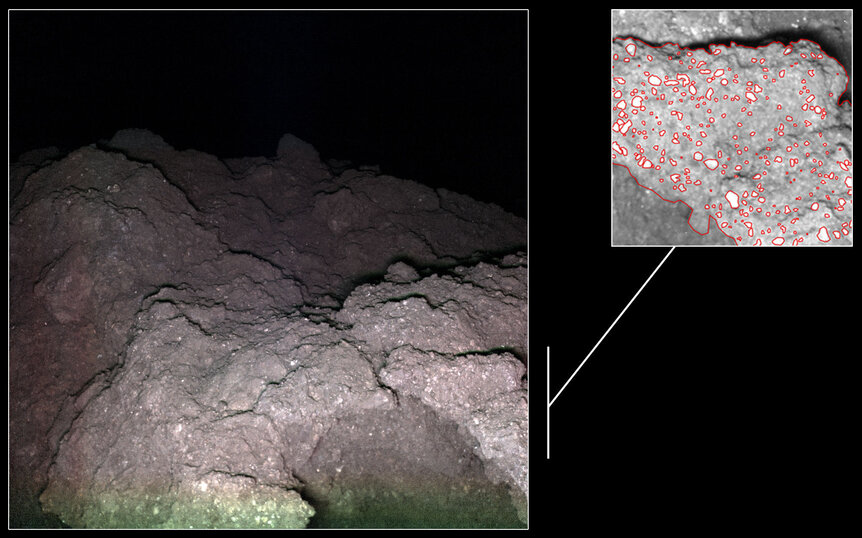

Several different types of rocks were seen by the main camera on Hayabusa2, but in the MASCOT images they can be divided into two main types: One kind is dark and rough — they describe it as like cauliflower-shaped — which is rough on small scales. An instrument on MASCOT called an infrared radiometer (it measures how bright the surface is in IR, which tells scientists about its composition and temperature) indicate the dark rocks are crumbly, brittle.

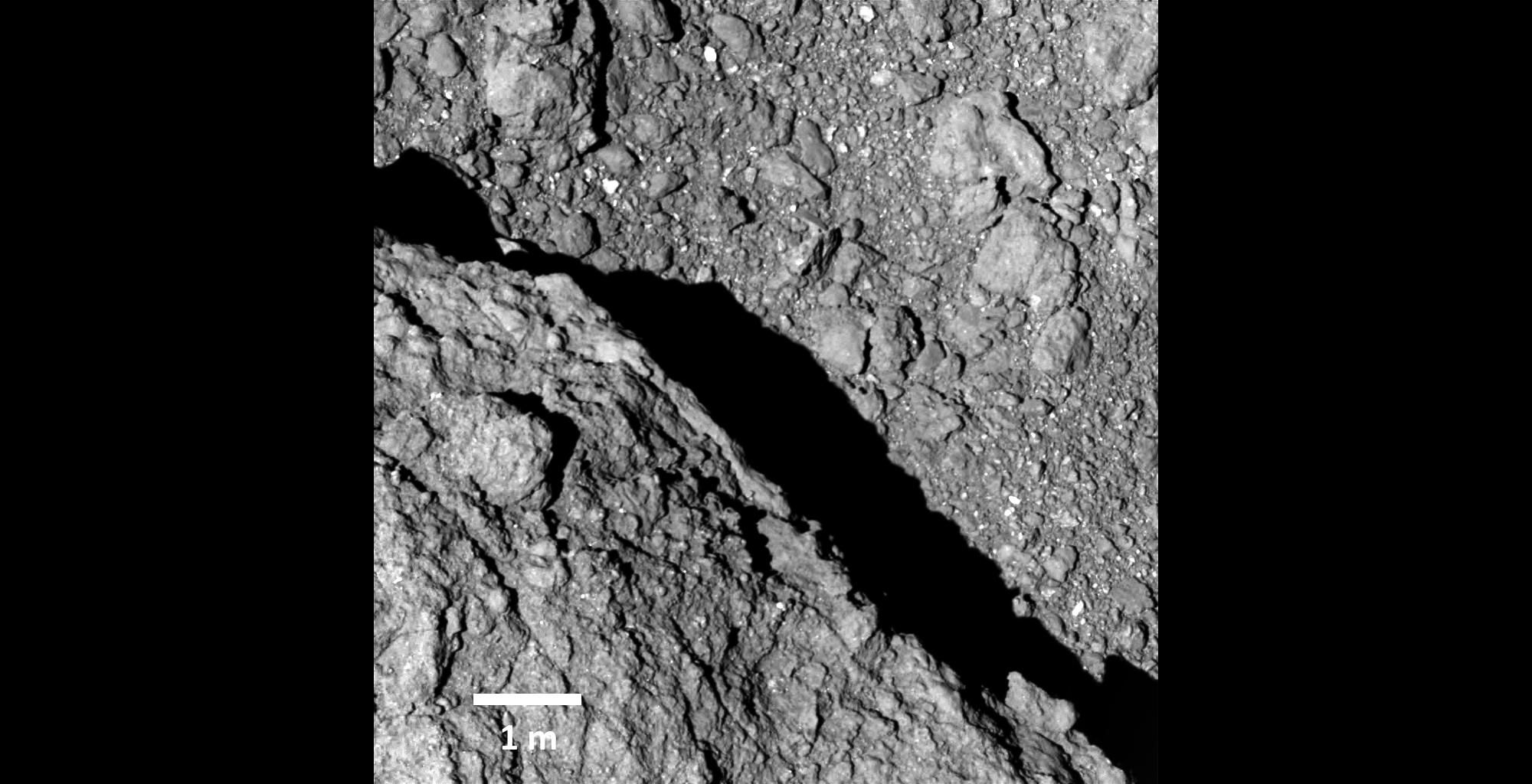

It also shows the overall surface rock structure (and, by extrapolation, the interior) is very porous, with about 28% of it being empty space! This fits with what we know of Ryugu's overall composition; it’s a rubble-pile asteroid, made up of rocks of different sizes held together by their own gravity, as opposed to one solid monolithic chunk.

The other kind of rock is much brighter and smoother, with wide faces and sharp edges. Both kinds are spread evenly across the surface, which indicates they're mixed together pretty well.

Why would that be? It must relate somehow to the origin of Ryugu. Maybe two different small asteroids of different compositions collided hard enough to shatter each other (if they were both rubble piles this would’ve been easier), which then dispersed a bit and resettled back together under their mutual gravity, with the rocks from both bodies mixed. It's also possible they came from different parts of the same parent body that got shattered after an impact, and they came together later. That last one seems less likely to me, to be honest, but it’s not possible to say right now what happened to form Ryugu.

The dark rocks have a surprise: Lots of much brighter bits of a different mineral in them, making them sparkly! These are called inclusions, and the scientists examining the data guess they might be olivine, a simple mineral common in many asteroids and planets (our own mantle is mostly different kinds of olivine). In fact the dark rock, which reflects a mere 4.5% of the light that this it, most closely resembles a kind of meteorite called carbonaceous chondrites. These are also dark, and are "primitive," which in this case means they likely formed very early in the solar system, maybe even before the planets did, and haven't changed much since then. Many of these kinds of meteorites don't have inclusions in them tough, which planetary scientists think may be due to them being exposed to water for some time, which can dissolve the inclusions. The fact that the dark Ryugu rocks do have them means it was at most only moderately wet at some point in its past.

Mind you, Hayabusa2 is also a sample return mission. It has already collected samples that will be sent to Earth in a couple of years. Once those are in hand, scientists will be able to compare the rocks to meteorites directly. That's amazing.

Another very interesting bit of info from the images is the complete lack of dust on the surface. Like, none. There are lots of agents of weathering on an asteroid's surface: the solar wind, cosmic ray hits, micrometeorites, and even thermal stress due to the day/night cycle (temperature swings of 100°C over the course of a Ryugian day were measured) can cause rocks to split. Certainly dust is made, but the complete lack of it on the surface means it either was ejected into space or dropped down below the surface. My bet is on the latter. Small collisions shake the asteroid, as would rocks splitting from thermal stress, and that might shake it enough to sift the smaller dust particles down into the interior. I'd love to pull away rocks on it to see! Until then, though, it's a mystery.

I have to mention the journey MASCOT took, too. According to the paper, it was dropped from an altitude of 41 meters from the surface of Ryugu, and when it impacted it bounced another 17 meters before coming to rest. The whole thing took six minutes! Gravity there is weak*.

MASCOT has an arm on it that allows it to flip itself over and to pop up off the surface and move around. It flipped over after landing with its camera pointing up into space. The images taken reveal it saw Jupiter, Saturn, and a star called Sigma Sagittarii! I just think that's cool.

It moved to different locations twice more, and even made a "microjump" to shift its position by a few centimeters so that it could take images of the scenery from slightly different angles, providing scientists on Earth with stereoscopic views and letting them determine distances to and therefore scales of some of the features. Clever.

The entire mission for MASCOT lasted 17 hours and 7 minutes. That's not long, but then, it did get to reveal a lot of secrets of a whole new world. That's a pretty good use of the short time it had.

*I'll note that an earlier press release indicated the release was from 51 meters and took 20 minutes. I'll assume that this later paper is more accurate since they had more time to analyze the telemetry.