Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The Earth has a new minimoon! But not for long…

On February 15, 2020, a pair of astronomers spotted a faint asteroid moving across their telescope's field of view. This is pretty common — they were observing as part of the Catalina Sky Survey, a collection of three telescopes in Arizona that scans the skies looking for near-Earth objects, asteroids that orbit the Sun and get near Earth.

But this one was different. It's not orbiting the Sun, it's orbiting the Earth!

That makes it a rare object indeed: a minimoon.

It was announced on February 25, and one of the astronomers, Kacper Wierzchos, recently tweeted about it, putting up the discovery images as an animated GIF:

Oof, yeah. That's faint. It's about 20th magnitude, which means the faintest star you can see by eye is a million times brighter. That's why these things are hard to find.

The asteroid, now called 2020 CD3, is pretty small, very roughly 2–4 meters across. So, about the size of a car. It was first seen using the Catalina survey's 1.5-meter telescope on Mt. Lemmon, but follow-up observations from other observatories quickly confirmed its existence and the fact that it's orbiting the Earth. Sometimes these objects turn out to be human-made artifacts, like rocket boosters from deep space missions or even Apollo boosters. But this one's orbit doesn't match any such object, making it essentially certain it's natural, an asteroid. It likely had a very Earth-like orbit around the Sun, allowing it to approach Earth slowly and get captured. The physics of this is tricky (a technical paper outlines the process) which is why this sort of thing is rare.

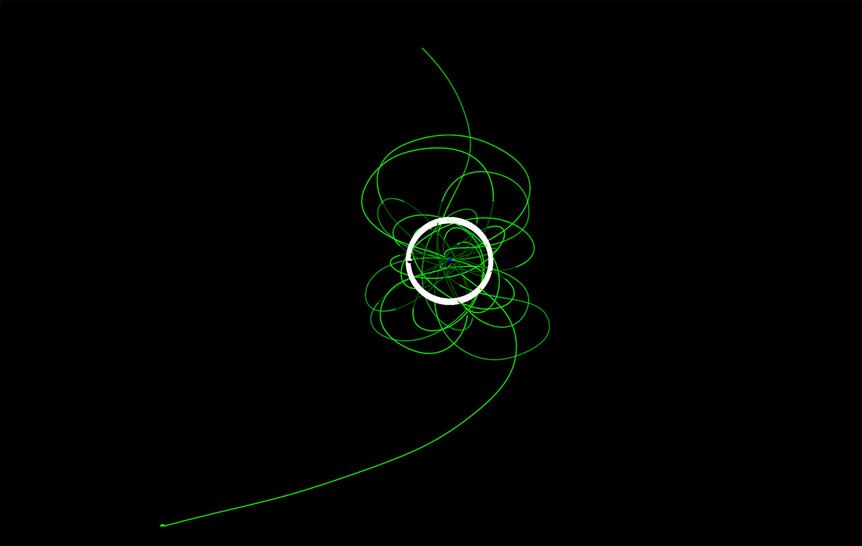

Interestingly, backtracking the orbit indicates it's been orbiting the Earth since late 2017! The orbit is messy, changing constantly due to the combined gravity of the Earth and Sun, as well as getting gravitationally tugged by the Moon. Amateur astronomer and physics teacher Tony Dunn has an orbit simulator package online, and he put in the orbital characteristics of CD3 to map out its position over time.

In the animation in that tweet, you're looking down on the Earth with the Sun off the screen far to the left. This coordinate system follows the Earth as it goes around the Sun, so it looks like the Earth stands still. The Moon orbits us at about 385,000 km (white circle). CD3 comes in from the top, tracing out that loop-de-loop for a few years. Over time, though, the orbit isn't closed; that is, it doesn't stay bound to Earth. Too many encounters with the Moon give it enough energy to be ejected, and in March/April 2020 it gets flung off to the left. As you can see too it doesn't get all that close to Earth, and sometimes gets a million kilometers out before looping back.

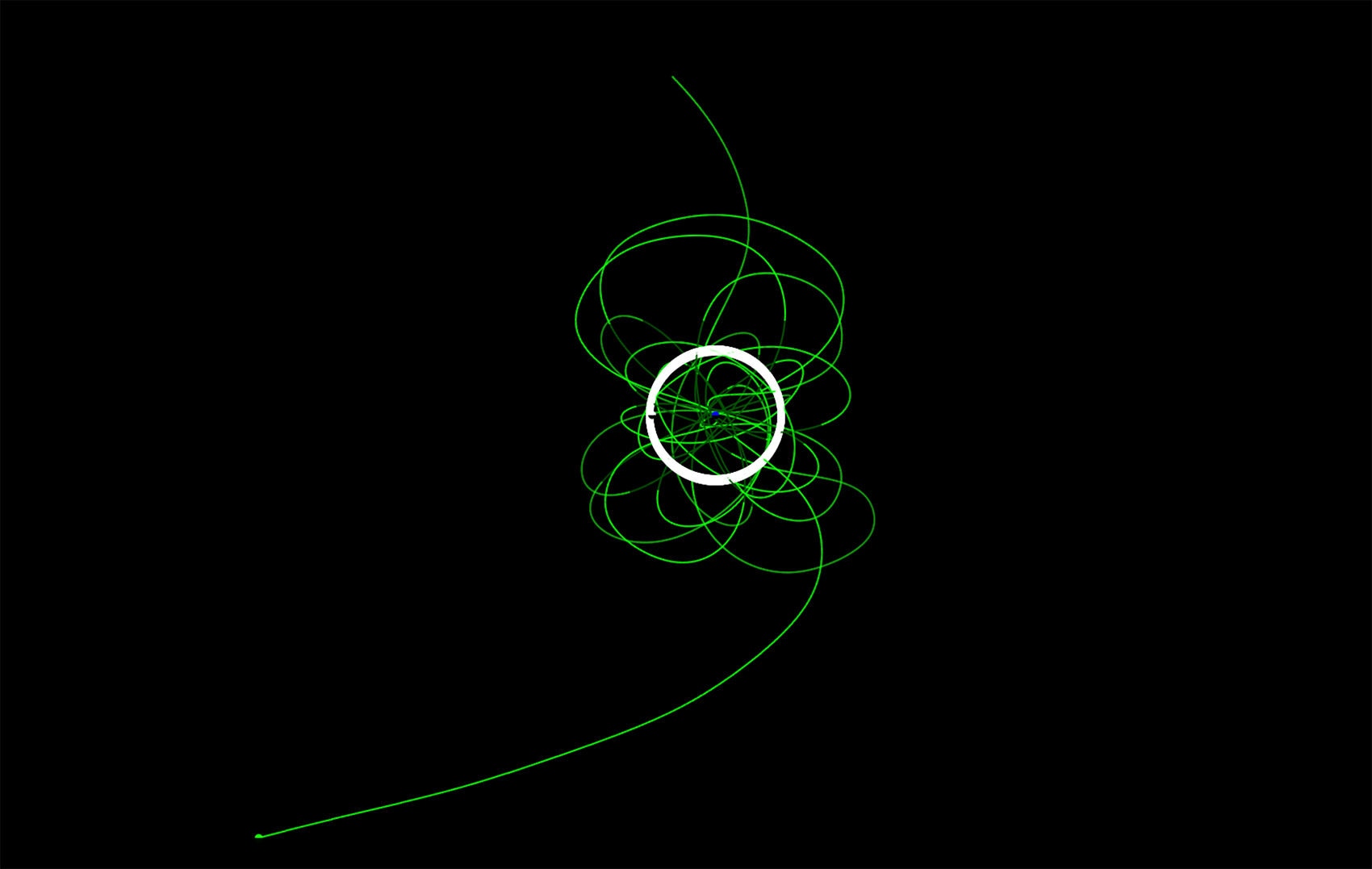

He created another view, seen closer to the Earth's orbital plane:

Here, the lower angle makes the Moon's orbit look more like an ellipse, and CD3 is traced using a red line. Again, you can see it dancing around us for years, then zipping off a couple of months from now. This means that right now may be our only chance to observe it before it gets too far away. After that, its simply too faint to see.

Finding minimoons — technically, Temporarily Captured Objects, or TCOs — is very rare. The first was 2006 RH20, which orbited the Earth a few times from 2006 – 2007 before being ejected into deep space. It was likely about the same size as CD3, a couple of meter across.

I recently wrote about what may have been the second one ever found. It doesn't have a name, because it was only discovered after it burned up in Earth's atmosphere in 2016. Multiple observations of that one allowed astronomers to trace its path back into space, where, given the uncertainties in the calculated orbit, they found it had a 95% chance of being a minimoon. It was likely about 20 cm across (volleyball-sized), but since its orbit cannot be confirmed we can't be 100% sure it was a TCO.

So CD3 is the second confirmed one. But it certainly won't be the last. In fact there are probably quite a few very small objects orbiting the Earth right now, far too small to see. But bigger ones, in the meter size range, come and go fairly often. It's pretty likely more will be found, especially since bigger telescopes with huge fields of view are coming online soon, including the immense Vera Rubin Observatory.

These objects are of some scientific curiosity. A curiosity that can be sated: Because they orbit the Earth, even for a short time, they are easier to visit via spacecraft than many other asteroids. Sometime, perhaps not too long in the future, we can have a rocket and spacecraft ready to go in case one that's particularly interesting happens to drop by. It's not that easy (the constantly changing orbit means we'd need lots of extremely precise observations to predict its path and match orbits) but it's possible, and then we'd be able to see one of these objects close up.

But that's a ways off. First we need to find more of these critters, get some better observations and numbers on them, so we can start to understand them more. After all, if they're going to go to all this trouble to get this close, the least we can do is take a closer look.