Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The galaxy that shouldn't be there

It's generally said that discoveries in science tend to be at the thin hairy edge of what you can do -- always at the faintest limits you can see, the furthest reaches, the lowest signals. That can be trivially true because stuff that's easy to find has already been discovered. But many times, when you're looking farther and fainter than you ever have, you find things that really are new... and can (maybe!) be a problem for existing models of how the Universe behaves.

Astronomers ran across just such thing recently. Hubble observations of a distant galaxy cluster revealed an arc of light above it. That's actually the distorted image of a more distant galaxy, and it's a common enough sight near foreground clusters. But the thing is, that galaxy shouldn't be there.

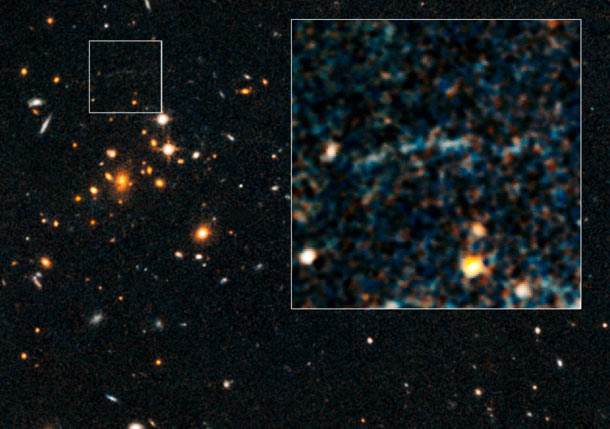

This picture is a combination of two images taken in the near-infrared using Hubble. The cluster is the clump of fuzzy blobs in the center left. The small square outlines the arc, and the big square zooms in on it.

The cluster is unusual. It's at a distance of nearly 10 billion light years away. Clusters have been seen that far away, so by itself that's not so odd. The thing is, it's a whopper: the total mass in all those galaxies combined may be as much as a staggering 500 trillion times the mass of the Sun, making this by far the most massive cluster seen at that distance.

But that arc... First, things like this are seen pretty often near clusters. They're gravitational lenses: the gravity from the cluster bends the light from a more distant galaxy in the background, bending its shape into an arc. See Related Posts below for lots of info and cool pictures on these arcs. In this case, I'll note the shape of the arc implies the biggest galaxy in the cluster, the one right below the small square, is doing most of the lensing.

But here's the problem: the galaxy whose light is getting bent has to be on the other side of the cluster, and that cluster is really far away. Note only that, the galaxy has to be bright enough that we can see it at all. Combined, this should make an arc like this rare. Really rare.

So rare, in fact, that it shouldn't be there at all! The astronomers who did this research worked through the physics and statistics, and what they found is that the odds of seeing this arc in this way are zero. As in, what the heck is it doing there at all?

Now we have to be careful here. What we have is one observation of one arc, and it happens to be behind an extraordinarily massive cluster. It's hard to extrapolate exactly what this means. Maybe galaxies formed more vigorously than we thought in the early Universe, so there are more than we might suppose. Maybe it's a huge coincidence, with a bright galaxy behind a massive cluster. Maybe the galaxy in the cluster doing most of the heavy lifting is surrounded by more than the usual amount of matter, making it an even stronger lens. Interestingly, using the arc itself, astronomers calculated the mass of that one big galaxy is something like 70 trillion times the mass of the Sun, making it bigger than most entire clusters at that distance!

If you get one weird thing happening, you might be able to shrug it off as coincidence. But two? In this case the existence of the arc at all coupled with the huge mass of this galaxy and cluster make me think there's more going on here than we see. Still, it's not clear what it might be.

One thing we can't dismiss is that our models of the early Universe might be wrong. Well, we know they're not perfect, so the question is really, how wrong are they? I expect we'll be hearing from people who think Big Bang cosmology itself is wrong -- and I'll be clear: it isn't. Those people are.

I also expect we may hear from people who don't like the idea of dark matter, either. This is the mysterious stuff that we know is out there -- and yes, we know it's out there -- that appears to have something like 90% of all the mass in the Universe. Our models of the early Universe depend on this stuff, and this new result may throw a monkey in the wrench for that. We do know there's a lot about dark matter we still don't understand yet. But this arc doesn't mean we have to throw out all of dark matter theory; just that we may yet have some tweaks yet to go before we understand the Universe better. It would take a lot more than just a few odd examples before we'd be ready to dump an idea like dark matter that goes a long, long way to explaining so many other things.

But therein lies the beauty of all this! Old models do get overthrown, and we're willing to do it once the evidence is strong enough. This gravitational lens observation is not enough to do it, but it may be part of a bigger picture that will. Or, more likely, there's a simpler explanation that we just don't know yet.

After all, this is science! If we knew everything already, we wouldn't be doing research. There's a lot about the Universe we have yet to understand. That's why this is so much fun.

Image credit: NASA, ESA, and A. Gonzalez (University of Florida, Gainesville), A. Stanford (University of California, Davis and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory), and M. Brodwin (University of Missouri-Kansas City and Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics)

Related Posts:

- Funhouse galaxy

- Galaxies swarm and light bends under dark matterâs sway

- Dark matter, apparently, is midichlorians

- The galaxy may swarm with billions of wandering planets