Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The Perils of the Skeptic Journalist

Being a writer these days is fraught with peril. Everything you write goes out into the wild, potentially viewable by millions of people. Usually not, but it can happen. And it may not happen today, or tomorrow … but those words are out there, and someone may stumble on them a year from now, or more.

That’s an abyss that can be hard to face. As someone who’s been writing for a living for a while now, I’ve stood at that edge long enough to be familiar with it, if not actually comfortable there. I know that something I say may be overturned by time, shown wrong by updated information, or just made stale as tastes and public attention evolve.

Of course, sometimes I’m just wrong. I can deal with the others, but just being plain ol’ wrong can be a tough one.

Oh, and I’ve been wrong. The mistakes I’ve made in my articles have ranged from just simple, unimportant stumbles to some that actually cut to the heart of the point I was trying to make. Even those big ones don’t necessarily bug me too much, if the mistake is an honest one: Due diligence was done, the research was performed, but the wrong conclusion was reached.

It’s not always like that though. Sometimes the mistakes are just dumb. Self-inflicted. And this week I’ve made a few. I want to ask for your indulgence while I point them out.

Why? Well, science—meaning the seeking of reality, of truth, of objective knowledge—progresses in some ways by making mistakes, and by examining them openly. That way, we can figure out what went wrong and try to avoid doing it again. And as a skeptic, someone who tries to examine evidence honestly, airing out my errors helps keep me honest.

What follows are my mea culpae. Per errata ad astra.

The UFO and the Deer

On April 10, 2014, I posted an article deconstructing a news story about a trailcam in Mississippi that took pictures of some deer at night. It also caught a strange glow, and several weird shapes. I’ve seen that sort of thing before—internal reflections of light in the camera—and immediately figured that’s what these were. The source of light occurred to me immediately; I checked some software, and sure enough the full Moon rose within minutes of the pictures being taken. Done and done, I figured.

Except I wasn’t quite right. It turns out the reflections were not due to the moon, but instead were from bright infrared LEDs on the camera. The folks at Parastupid have a pretty good breakdown of this. It’s funny; the heart of what I was saying was actually right; it wasn’t a real object creating the glow, but just reflections. I was wrong about the source. My thanks to Alex Parker for a series of tweets pointing me in the right direction as well.

The thing is, the news story played up the mysterious aspects of this event, and I took the reporter to task for not investigating it more thoroughly. It bugs me when I see reports of UFOs or the like, and no real digging occurs.

But in a sense that’s just what I did. I found my explanation, found the support for it, and figured I was done (especially since I’ve seen the Moon mistaken for a UFO before). I should’ve thought further to try to find other explanations. If I had looked at the camera more carefully I would’ve seen the LEDs, and that would’ve made this whole thing pretty obvious.

Next time, too, even if the timing is perfect (like it was for the rising Moon in the video), I’ll try to remember that coincidences happen. That doesn’t make the obvious explanation the right one. And I’ll make sure my own methodology is sound before going after someone else’s.

The Martian Beacon

This one is similar to the one with the deer and the UFO. In a recent image of the surface of Mars taken by the Curiosity rover, there was an odd flash of light that appeared to be off in the distance. I saw right away that the blip of light looked very much like cosmic ray impact—subatomic particles from space hitting the detector–which I had seen literally thousands of times in Hubble images I worked on.

Since I wasn’t familiar with Curiosity images, I asked a friend who was, and she agreed they were cosmic ray hits. Case closed, I figured. I wrote up my post, and that was that.

Except not really. Another expert on Mars hardware said it may have actually been a “light leak,” a bit of sunlight that somehow got into the camera through a hole, or crack, or seam somewhere in the hardware. He also says it may be a sharp reflection of sunlight off a glinty rock. Those are certainly plausible, though right now we don’t have enough evidence to say for sure which of these explanations may or may not be the right one.

But the point is there were other possible explanations than a cosmic ray, and I should have entertained that idea. I didn’t; I came upon a plausible solution and ran with it—and while I confirmed it (and I am not putting any onus on my friend; this is all on me), the first answer I got fed into my own bias so I didn't question it as much as I should have. And like the other story, I took the reporter to task for not looking further. Arg!

This reminds me of my favorite line in the Sermon on the Mount: “Seek not the glint in thy brother’s eye; canst thou not see the infrared LED reflection that is in thine own?”

I’m paraphrasing a bit. But either way, my apologies both to the reporters and my readers over this.

The Rock and the Skydiver

A video went viral last week purporting to show a meteoroid—the solid chunk of space debris that is called a meteorite once it hits the ground—passing by a skydiver. At first I thought it was plausible and wrote a post basically taking the tack that the video looked real (as opposed to a deliberate hoax), whether or not the object was actually a meteoroid or something else. But then more evidence built up that it really was just a rock that fell out of the skydiver’s parachute (this is surprisingly common). I wrote a second post at that point, saying I couldn’t be sure, but if I had to bet, I’d bet rock.

Then I got an email from Steinar Midtskogen, one of the people who made the video, and he was admitting they had to face the fact that it was almost certainly a rock. All well and good, but by that point I had noticed a second object in the video, which I took to be more debris falling out of the parachute. While I was pretty sure the first object was a rock by then, the second one convinced me. So I wrote a brief, final post to wrap everything up.

But then Midtskogen emailed me again, saying that they had also seen the second object, and that it was most likely another skydiver on the same jump. Oh! Well, that was certainly plausible, so I updated my post saying so.

Then confusion reigned. I got tweets and emails asking me why I still thought the first object was a rock, when it turned out the second object wasn’t a rock. So I wrote an update, pointing out that my conclusion didn’t depend on the second object, it was just strengthened by it. To me, it pushed my opinion from 95 percent sure to 99 percent, but going back to 95 percent wasn’t so bad. And again, the team had already come to the same conclusion, so I felt pretty safe in mine.

In this case, sure, I made a mistake, and should’ve examined the video more closely to see if the second object could’ve been the other skydiver (who does show up in the video). Luckily, it didn’t really matter, but it was still an error, and it caused confusion among my readers. That’s a situation I try very, very hard to avoid. These things can be confusing enough without me making them worse! I should’ve been more clear on why the second object was neither here nor there when it came to the overall picture.

The Skeptic Ouroboros

Being a skeptic is hard. It’s not easy to try to weigh evidence for everything, be methodical, critical, aware of bias, and come to a conclusion that you’re willing to drop if better evidence comes along. Worse, many times the things you are being skeptical of are cherished beliefs and values held by others, and that’s a fun little path to walk down. It can provoke some pretty, um, strong reactions in people.

But the absolute hardest thing of all is to be skeptical of your own skepticism. Did I miss something? Did I think of other explanations? Am I biased in some way, jumping to a conclusion because I think I know the answer?

How might I be wrong?

I rather blew it a few times this past week by not asking those questions. I’ve been a skeptic a long time, but this is pretty good evidence that you never perfect the technique. Being skeptical is a journey, not a destination. You just have to keep trying.

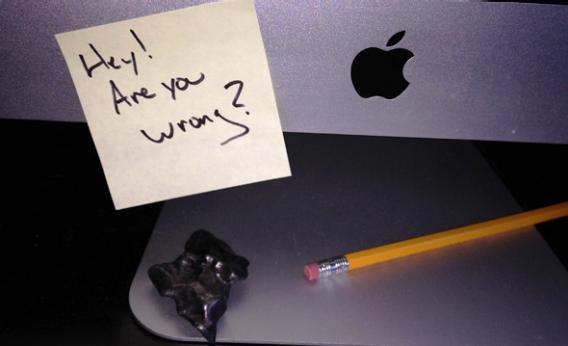

I’ll keep trying. And just to help, I’ve left myself a little note stuck to my monitor to remind me. Now I just have to remember to check it before clicking that “publish” button every day.