Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

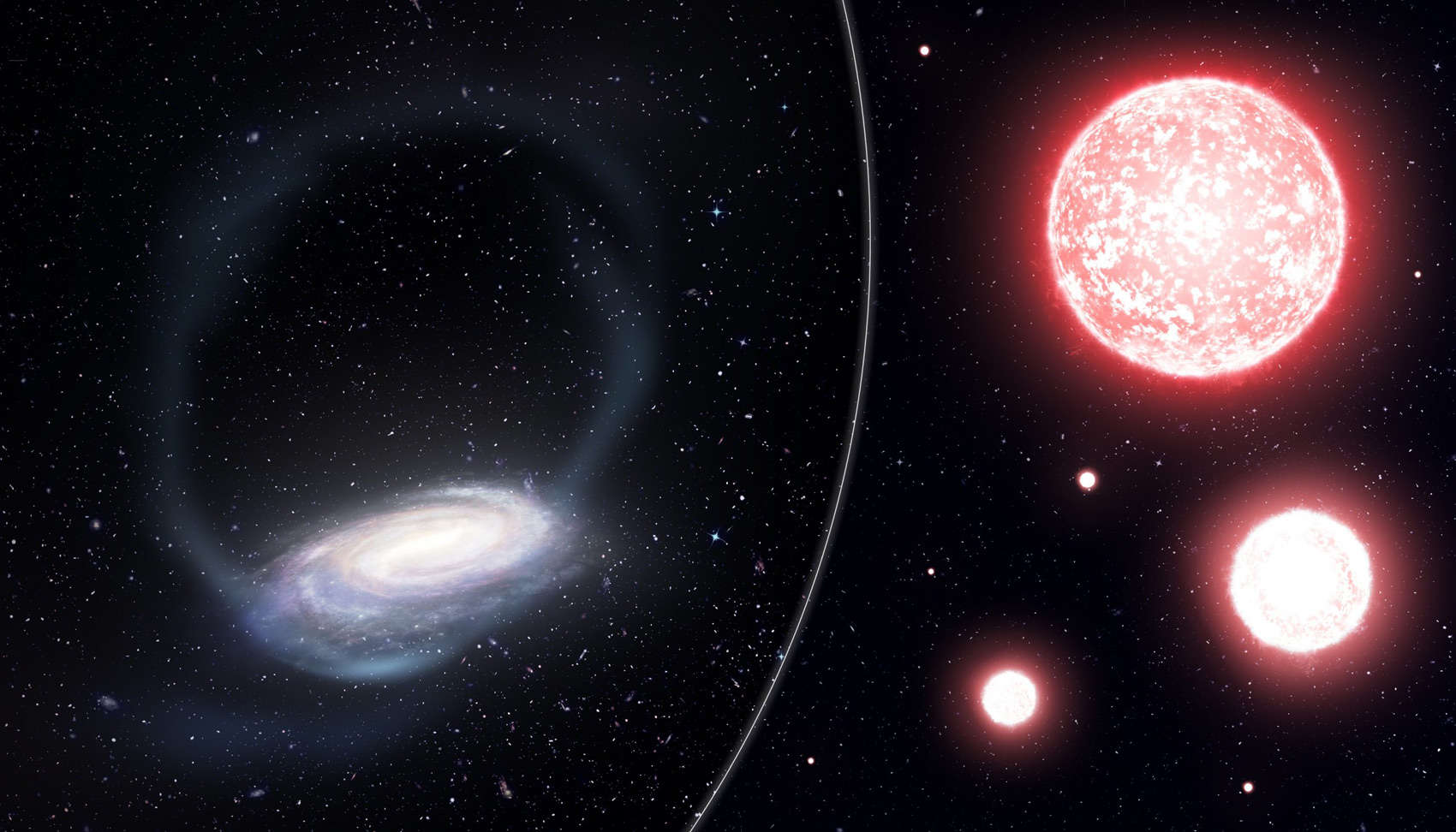

The Phoenix star stream, remnant of a long-dead stellar city

Astronomers have found a stream of stars circling the Milky Way, like an elongated clump of cars moving together on circular racetrack. Many such streams have been found before, but this one is different: The stars in it are very old. Very. So old — 11.2 billion years — that they may have been the sole survivors from a lost generation of star clusters that once orbited our galaxy, but have long since been torn apart by it.

Ironically, the name of this structure is the Phoenix star stream. Not because it rose from the ashes of that long-ago population, but because it's in the constellation of the Phoenix. Still: fitting.

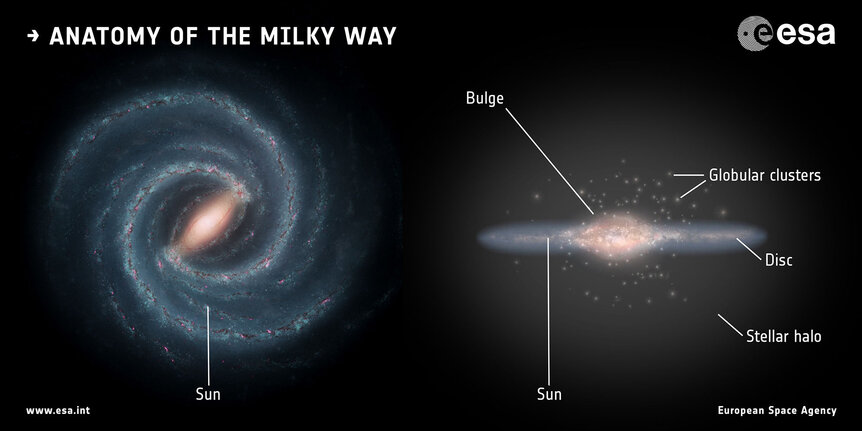

The rise of huge surveys of stars, where millions or even over a billion stars are catalogued and measured, has shown us that the galaxy is littered with long streams of stars all traveling on similar orbits. We think that these are the remnants of old star clusters or even satellite galaxies from long ago. As they orbited the Milky Way, our much larger galaxy's gravity teased them apart, pulling them like taffy into long thin streams of stars.

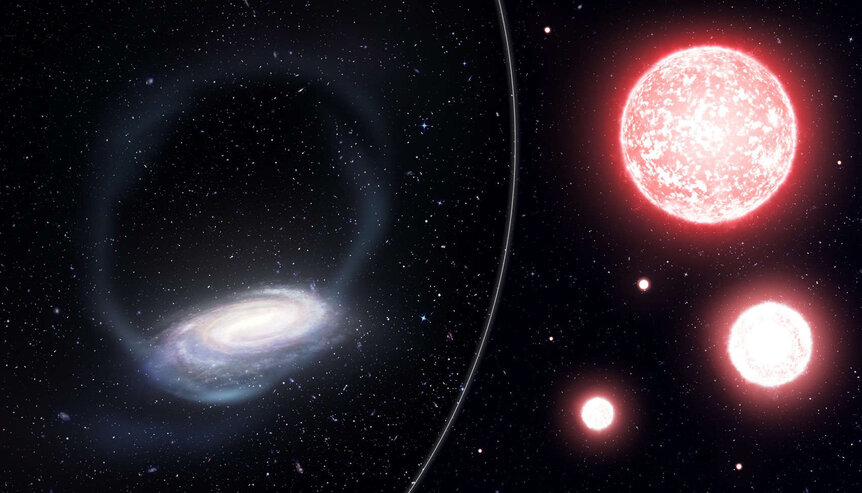

The Phoenix stream was discovered in the Dark Energy Survey, a huge wide-field survey that was designed to look at distant galaxies but also saw millions of stars in our own. The Phoenix stream is a thin spaghetti strand of stars between 8,000–14,000 light years long but only 170 wide. It's about 60,000 light years away from us.

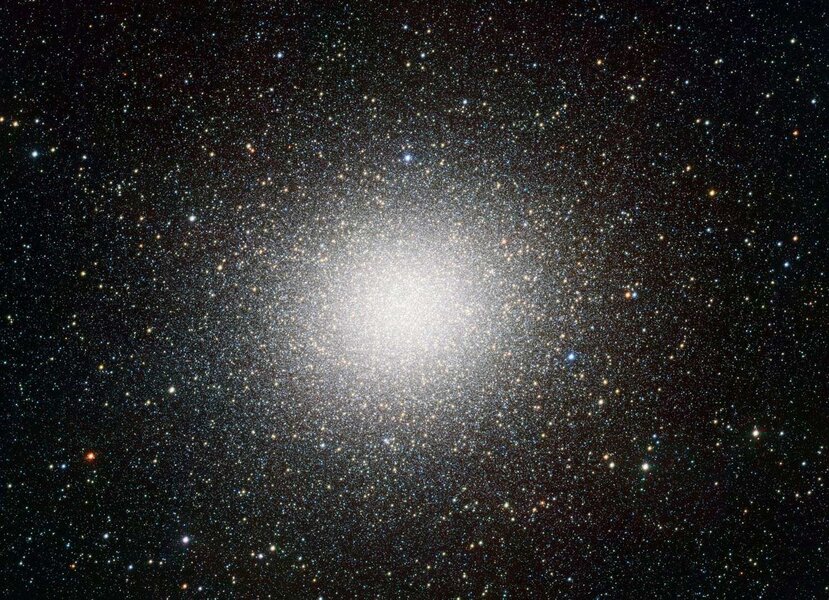

Given the narrow width, it must be from a disrupted dwarf galaxy or a globular cluster — a spherical collection of hundreds of thousands or millions of stars. Those can be a couple of hundred light years in size or less.

But, as I said, the stars in the Phoenix stream are incredibly ancient. We know this because they have a profound lack of heavy elements in them.

So, if you'll forgive me, a slight digression…

In the beginning…

[OK, that's a big digression, but hang on. You'll see.]

… the Universe was a simpler place. After the fires of the Big Bang cooled, matter was mostly hydrogen and helium, the simplest elements, with just a soupçon of lithium as well. Once stars formed millions of years later, the fusion reactions in their cores that powered them made heavier elements, converting hydrogen and helium into carbon, oxygen, iron, and more.

Astronomers call these heavier elements metals. It's a little confusing if you're not used to it, but just think of them as “heavier than hydrogen and helium” and you'll be fine.

Most stars in our Milky Way galaxy now have those metals in them because they were born later, after a previous generation of stars created them. Also, our galaxy is surrounded by some 160 globular clusters, and the stars in them tend to have an even lower abundances of those metals, indicating the cluster stars are very old. But they also have what's called a metals floor, a lower limit to that abundance. The stars in the clusters are old but not first generation, so they still have some small amount of metals.

This is why the Phoenix stream is so very interesting. The stars in it have an abundance lower than the globular cluster floor. That means they're even older.

Nothing like this has ever been seen before. Interestingly, the stars in the stream also have almost no difference in their individual abundances. If they came from a small galaxy (generically called an ultra-faint dwarf galaxy) then they'd have some spread in their metal abundances, because they would've formed at different times. Also, most galaxies like this orbit the galaxy in the opposite sense of the galaxy's spin, while the stream moves in the same direction.

That sounds a lot more like a globular cluster, since very old ones have very similar stars and orbit the galaxy in the same direction as its spin. But if so, the stars in the Phoenix stream came from an even older population of globular clusters, a population we don't see any more.

Putting this all together, it looks like there was once a generation of globulars orbiting the Milky Way long ago. Over time these all were destroyed, and their streams merged with the galaxy at large (and perhaps our halo, a huge spherical cloud around the Milky Way that suspiciously has a decent population of very old low-metal stars). The Phoenix cluster was an exception; for some reason it held together a little bit longer than its siblings, and we can still see its scattered remnants today.

… but is it, really? An exception I mean. It was only just found recently due to these surveys, and there may be other such Methuselah streams waiting to be found in the data; perhaps Phoenix was just the brightest and easiest to spot. If so, then we may yet have a window open to the earliest days of our galaxy, when the Universe itself was very young.