Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Wait. *How* big is Antares?

Stars are immense objects. We toss around words like "big" and "huge" all the time, but what does this mean on a human scale?

After all, the Sun is a mind-crushing 1.4 million kilometers in diameter, wide enough that you could line 110 Earths side-by-side across it.

And there are stars much, much larger than the Sun.

Antares is a red supergiant, with a dozen or so times the mass of the Sun. Stars like that fuse elements in their core so rapidly that they blast out light, and it may radiate energy at a rate as much as 100,000 times as much as the Sun does. That's why, even though it's something like 500 light years away it's still one of the brightest stars in the night sky, an angry red beacon sometimes called "The Heart of the Scorpion" due to its location in the constellation of Scorpius.

When massive stars near the ends of their lives, they swell up and cool off; the spectrum of their light shifts to red, and they become supergiants. But how super is "super"?

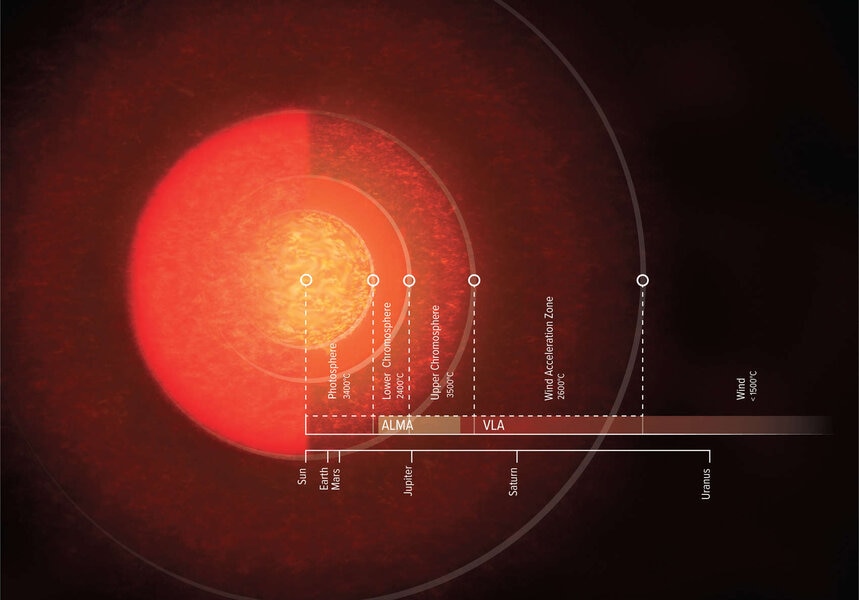

In the case of Antares it's enormous. Vast. Its photosphere — the part you'd call the surface as seen by eye — is nearly a billion kilometers in diameter, and would reach well past the orbit of Mars if it were in the center of our solar system.

But new observations show that other parts of it extend well beyond that. If you include its chromosphere, wind acceleration zone, and lower part of its wind, it reaches out to a staggering 12 billion kilometers! Replace our Sun with Antares and that would swallow the entire solar system of major planets.

The parts of a star you see depend on how you look at it. By eye, the photosphere is the outermost surface of the Sun, for example; it's where light from the interior finally frees itself and can fly unabsorbed into space. That's what we normally think of as the "surface" of the Sun. But there's a layer above that called the chromosphere; it's normally invisible by eye but can be seen during a total eclipse. It's a layer of hot hydrogen that glows characteristically red (hence its name, since "chromo" means "color"). The Sun's chromosphere is about 3000 – 5000 km deep (less than 1% of the Sun's radius).

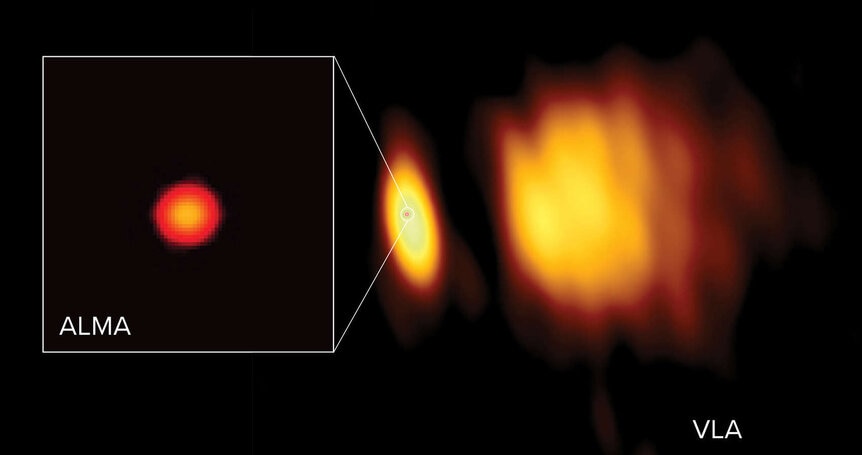

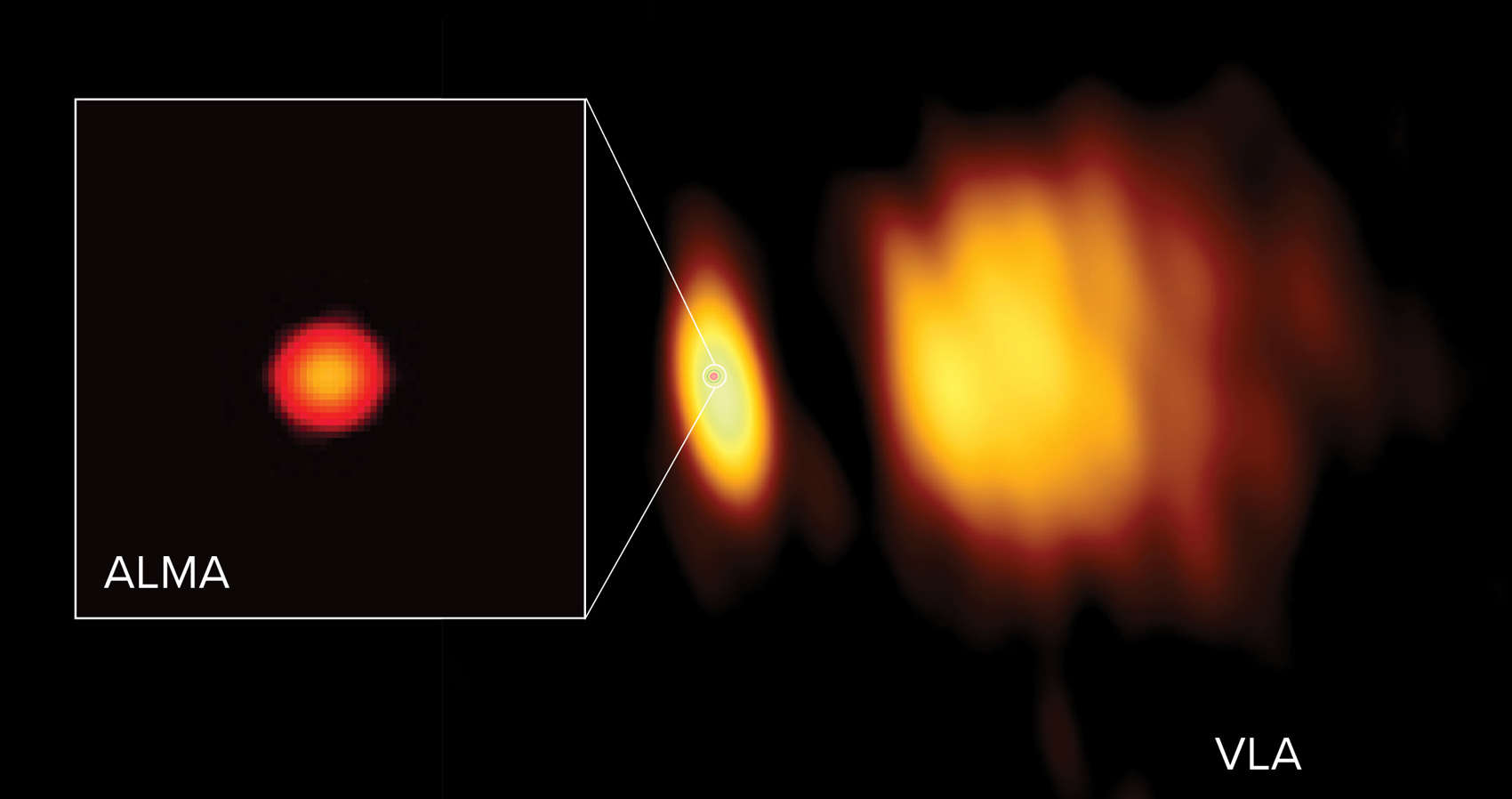

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile, which observes in wavelengths in the millimeter range (between far infrared and radio), astronomers measured the chromosphere of Antares and saw it stretches out to 2.5 times the star's photosphere! That's a radius of roughly 1.2 billion km, comfortably larger than the orbit of Jupiter.

Using the Very Large Array (or VLA) in New Mexico, which sees in radio light, they also measured a layer in Antares above that called the wind acceleration zone. This is where the material at the top of the star is flung outwards, creating a wind analogous to the Sun's solar wind. This part was seen out to six times the size of the photosphere, a radius of nearly 3 billion km, and the wind itself traced out to double that distance!

We can't see those layers with our human eyes, but our metal radio-sensitive ones all over Earth can. They saw something else, too. Antares is a binary star, and its companion star is a beast, with a mass 7 times the Sun's, and shining over 2,500 times as bright as the Sun. That star is hot and bright enough to illuminate the wind of gas blowing past it from its much larger primary star, and that can be seen in the VLA images as well.

Observations like this are important. We don't really understand how the winds from red supergiants are accelerated, for one. Pulsations in a star like this generate shock waves that create grains of dust that get lifted away as well, but how that works isn't understood either (as you may recall, that has caused some excitement about the red supergiant Betelgeuse recently). Mind you, red supergiants eventually explode as supernovae, so that's a fairly important reason to figure out what's going here.

Antares is no exception. It's easy enough to see now (literally; it's up high in the south for northern hemisphere people after the sky gets dark), but just wait until it goes all supernova on us. It'll be about as bright as the full Moon! After that it will fade as the debris expands, eventually becoming invisible to the eye (which you may already know if you read xkcd). In some ways we understand that better than we do the star itself.

So if you can, go out and take a look at Antares. Marvel at its brightness, its ruddy hue, and know that it's bigger than whole solar systems… but also that there's much more to learn about it.