Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

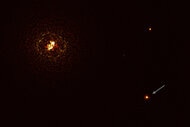

What if all the Kepler exoplanet candidates orbited one star?

This is pretty cool: astronomer Alex Parker took all the planet candidates found by the Kepler telescope - nearly 2300 planets in all - and made an animation showing what they would look like if they all orbited one star.

Dr. Parker had to do some scaling to make this work. For example, the actual size of each planet is known relative to its parent star, which he then scaled to fit the star shown in the animation. He scaled the distance from the star in a similar way. He describes it all on the page for the video.

I have to admit, it's hard to know if there's anything scientific we can learn from this. It's fun to play with data, and it does often happen that by doing so you can see hidden relationships, things that aren't obvious when displayed in normal ways (I've had that happen to me as well just playing with data - and Parker is very good indeed at playing with data; see Related Posts below for more cool stuff he's done). That may very well turn out to be true in this case, or it may simply turn out to be an interesting demonstration. But as he points out, since this is animation was done to scale using all the Kepler planet candidates, one thing you see immediately is that there is always at least one transit going on! In other words, looking at all the Kepler host stars, no matter when you look, there are probably a dozen transits or more occurring at that moment.

That to me is actually shocking. I mean, it makes sense, and given some thought I would've realized it on my own. However, the context I always put this in is that just a few years ago we didn't know of any transiting planets, and in fact for a while after the first were found a lot of astronomers scoffed at the idea. Now, though, the evidence is so overwhelming there is no doubt these transiting exoplanets exist.

And yet in all that time we didn't know these planets existed, in all that time astronomers were looking for them and didn't see them, in all that time some were found and other astronomers scoffed, there was never a time when there wasn't a planet transiting a star.

And that's just in the tiny patch of sky Kepler looks at; the entire sky is over 300 times bigger. So if there are a dozen or so transits going on in just the Kepler field, as Parker states, that means there are thousands of them going on in the sky even as you read this. Every day, all day, for millions and billions of years.

All those planets, perhaps millions of them, hidden in plain sight. All we needed to do was actually look for them.

So the usefulness of Parker's animation is clear to me; its impact on me was profound. It reminded me once again that science evolves, and that my own biases - all our biases - must evolve with it. Otherwise, who knows what we'll miss?

Tip o' the dew shield to the Scientific American blog.

Related Posts:

- Piano sonata in the key of Kepler-11 (music by Alex Parker based on planet orbits)

- Music of the spheres (more music by Alex Parker, this time based on supernovae)

- New study: 1/3 of Sun-like stars might have terrestrial planets in their habitable zones

- Motherlode of potential planets found: more than 1200 alien worlds!