Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The science behind 'Don't Look Up' and its planet-killing comet

We're probably going to be fine...

When audiences are given a movie about an apocalyptic collision with a space object, most of the time it's a tale of the heroic people aboard a ship charged with the mission of blowing that planet killer up, or folks tasked with building an underground arc for humanity's survival. What these movies don't do is take us on a two-hour tour through the worst parts of our society as the whole world argues amongst themselves about whether the impactor is even real and whether there's anything we could or should do about it. And then there was Netflix's Don't Look Up.

The recent film from Adam McKay follows Dr. Randall Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) and PhD student Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence) as they frantically try to warn the world of an impending extinction level event. Early in the movie, Dibiasky discovers a comet from the Oort cloud — a cloud of icy bodies between 0.3 and 3.2 lightyears away — which is hurtling toward the Earth. Its trajectory has it colliding with the planet in a little over six months with near total certainty. We won't spoil the movie for you here, but the version of humanity portrayed in the film makes a series of questionable choices about what, if anything, should be done about the impact.

But could a planet-killing object like this one be out there waiting for us? And, if so, what can we do?

ARE THERE PLANET KILLERS OUT THERE?

Yes.

That's obvious, right? We all know that.

We've been hit by large objects before, and they've caused planet-wide extinctions at least once in our history. The plot of this movie would be no surprise to the dinosaurs. They've seen it already with front-row seats.

That these objects exist isn't in question. What's less certain is if or when one of them will find itself at the same time and place as our pretty little planet. The good news is we have whole teams of really smart people with their eyes to the sky, looking out for objects which might pose a threat to our planet.

NASA's Planetary Defense program — which the movie references and, yes, it is a real thing — searches the heavens for comets and asteroids. Once found, they map their trajectories to calculate their likelihood of crossing paths with Earth. They're looking primarily for near-Earth objects (NEO) and potentially hazardous objects (PHO). The criteria for these involve both the size of the object and the nearness of its pass.

A quick look at the statistics supplied by Planetary Defense's Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) might be startling. Nearly 28,000 objects have been identified to date, and roughly 6,000 of those only in the last two years. That has less to do with the number of objects out there and more to do with our getting better at finding them, which is objectively a good thing.

Most of these objects are small enough that even if they did strike the Earth, they'd burn up in the atmosphere or else cause minimal damage. Nothing on the scale of a global apocalypse. Some of them though, are quite large. The most recent data shows 889 identified objects larger than a kilometer in diameter.

Worse, it's impossible to know exactly what an object's orbit will be. Incomplete data, solar forces, collisions with other objects, a whole host of variables go into figuring out where an object will be at a given date and time. As such, CNEOS calculates a range of orbits to come up with a probability of impact over hundreds of years.

The good news is, of all the known objects, there are none which pose a serious threat to the planet over the next century or so. Of course, that's based on the objects we currently know of. Something new could also come out swinging from the distant reaches of the solar system. If they did...

IS THERE ANYTHING WE COULD DO ABOUT IT?

Also, yes.

Phew, that's a relief. If we suddenly discovered an impactor on a collision course with us, we are not without recourse. In fact, just a couple of month's ago, Planetary Defense launched their first test mission.

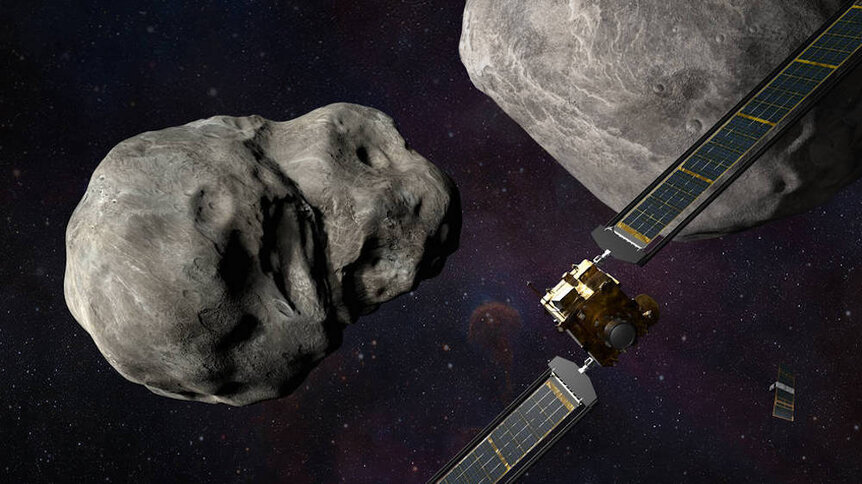

DART, which stands for Double Asteroid Redirection Test, is also carrying a secondary craft as a stowaway which will gather data in the later phase of the mission. The pair are on their way to the Didymos asteroid system. The larger asteroid, Didymos, is orbited by a smaller moonlet called Dimorphos.

DART is targeting the moonlet because it's relative orbit around Didymos is slower than their collective orbit around the Sun, meaning measuring the change in orbit will be easier. Later this year, DART will intentionally collide with Dimorphos at four miles per second, transferring its kinetic energy to the moonlet and slowing down its orbit. Before then, the secondary craft known as LICIACube will separate from DART to gather data during and post-impact.

Didymos isn't a threat to the Earth, but the information gathered from this mission will inform future plans for deflecting any hazardous objects discovered in the future. Basically, we're figuring out if a punch-first strategy could work for planetary protection.

Running headfirst into an asteroid or comet isn't our only strategy, however. Other proposals involve parking a large craft near an object and using its mass to slowly tug and shift its orbit over the course of years. There's also the ever-popular blowing stuff up plan which could be used to break up an object or similarly deliver kinetic energy sufficient to alter its trajectory.

No matter which strategy we choose, it's crucial that we have as much lead time as possible to spin up a craft, get it where it needs to be, and change an impactor's path early enough for it to do us some good.

That's why Planetary Defense and CNEOS are so important. As with most things, our best hope is an early warning.